COLONIAL STRATEGIES IN IOK

COLONIAL STRATEGIES IN IOK

The revocation of Articles 370 and 35-A on 5 August 2019 marked a decisive escalation in the Indian state’s control over Indian Illegally Occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IIOJK), signaling a strategic shift from intermittent repression to systemic domination. This unilateral constitutional amendment did not merely.

redefine the legal status of the region; it provided the foundation for a comprehensive restructuring of socio-economic and political relations, enabling the state to exercise unprecedented authority over land, property and civic life. In IR terms, this can be understood as an instrument of statecraft where sovereignty is exercised through domestic legal manipulation, effectively consolidating a colonial apparatus under the guise of national integration.

The abrogation served as both a legal pretext and a policy tool, legitimizing a variety of coercive measures that collectively constitute a strategy of property repression, a method of control designed to undermine local resistance and entrench structural dependency (Whitehead, 2022). The period after August 5, 2019, reveals a deliberate pattern of property-based coercion that is neither incidental nor reactive. Rather, it is a calculated extension of settler-colonial strategies observed historically in contested territories, whereby property expropriation functions as a mechanism of demographic and political control (Veracini, 2015).

The reshaping of legal frameworks has created conditions in which ordinary Kashmiris, including teachers, traders, lawyers and professionals, now face dispossession that reaches far beyond material loss, extending into the symbolic erasure of identity and history. The emphasis on property as a locus of control reflects a sophisticated understanding of how economic resources, spatial occupation and symbolic capital intersect in the reproduction of authority (Bourdieu, 1998). Such measures align with coercive state strategies used in asymmetric conflicts, where domestic law and bureaucratic machinery are

weaponized to neutralize dissent while projecting an image of legality and order internationally (Kreutz, 2020).

The strategic significance of property confiscation and demolition in IIOJK lies in its dual function: it serves both punitive and preventive purposes. On the one hand, the expropriation of land, homes and offices operates as a punitive measure against those perceived as politically inconvenient. On the other, it acts preemptively to reshape the socio-political landscape, rendering resistance structurally more difficult. The abrogation of Article 370 facilitated this duality by removing longstanding legal protections for local property ownership, thereby permitting non-locals to acquire land and settle strategically. This aligns with broader IR theories on territorial control and demographic engineering, in which altering population composition is employed to consolidate state authority and diminish the legitimacy of local political claims (Toft, 2014).

The post-2019 measures, therefore, should be read not merely as domestic law enforcement or urban planning,but as instruments of a calculated political strategy designed to achieve enduring dominance over contested territory (Yeh, 2013). The shift in laws and governance after the abrogation demonstrates a coordinated attempt to secure domestic legitimacy while managing the gaze of the international community. Labeling property seizures, demolitions and urban restructuring as lawful measures becomes a diplomatic tactic, shielding the state from external accountability while bolstering its internal political mandate (Anderson & Stavenhagen, 2022).

This creates a paradox wherein systemic repression is masked under bureaucratic and legal language, allowing the Indian state to navigate international criticism while materially reshaping the region. Such duality is central to the study of coercive governance in IR, showing how normative commitments to human rights are frequently subordinated to strategic objectives of territorial control, state consolidation and demographic manipulation (Milanovic, 2020).

'

This paper aims to interrogate these mechanisms by tracing patterns of property seizure, attachment and demolition in IIOJK post-5 August 2019. It seeks to demonstrate that these measures are neither arbitrary nor isolated, but rather constitutive of a larger, state sanctioned architecture of repression. The research further situates these practices within a colonial and settler-colonial analytical framework, arguing that property expropriation functions as a deliberate instrument to restructure power, erase local agency and normalize state domination (Wolfe, 2006). The emphasis on property, rather than solely on arrests or political suppression, reveals an often-overlooked dimension of control that directly affects economic security, social status and cultural continuity (Ghosh, 2022).

Finally, the objective of this study is to advance an understanding of how modern coercive strategies operate in hybrid conflict zones, where legality, militarization Patterns of Property Seizure and Confiscation5 and bureaucratic policy converge to produce systemic vulnerability. Documenting the patterns of property repression in IIOJK creates a crucial evidentiary basis for evaluating how these practices are reshaping local governance, undermining human security and challenging established international norms (UN OHCHR, 2018; ICG, 2020). It argues persuasively that property confiscation, when deployed strategically, is not merely an administrative act, it is a tool of structural violence that entrenches state authority, marginalizes indigenous populations and perpetuates colonial dynamics under the veneer of legal legitimacy (Farmer, 2004; Davis, 2019).

Methodology

This research adopts a qualitative, evidence-driven methodology designed to trace, verify, and analyse patterns of property confiscation and demolition in the region. The study relies on a multi-layered data collection strategy that combines documentary review, case mapping, and triangulated verification. Official notices, legal documents, administrative orders, and open-source material form the primary documentary base. Each case included in the study is cross-checked through at least two independent sources to ensure accuracy and eliminate anecdotal distortions. Spatial evidence—such as geotagged photographs, timestamped videos, and publicly available satellite imagery—is used to validate the scale and location of demolitions.

The analysis follows an interpretive framework that examines property actions not as isolated incidents but as components of broader structural practices. This methodology ensures that the findings are empirically grounded, verifiable, and ethically produced, while remaining sensitive to the political constraints of working in a highly securitized setting.

LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK FACILITATING PROPERTY REPRESSION

The systematic confiscation, attachment and demolition of property in IIOJK cannot be understood in isolation from the domestic legal framework and administrative machinery that enables it. Far from being arbitrary or ad hoc, these actions are underpinned by a complex network of statutes, executive directives and bureaucratic processes. These laws, combined with discretionary administrative mechanisms, create an environment

where property is no longer a private asset but a tool for political control, collective punishment and social engineering (Bhat, 2021; Zia, 2019). In the absence of judicial oversight and clear procedural safeguards, the legal and policy framework effectively facilitates repression under the guise of law and security (UN OHCHR, 2018; Ghosh, 2022).

Domestic Laws

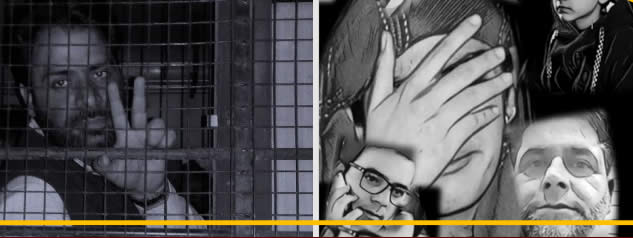

The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) of 1967, as amended multiple times, most recently in 2019, serves as the cornerstone for property-related repression in IIOJK (Chowdhary, 2020). Originally framed to counter terrorism, the act has been broadly interpreted to criminalize dissent and target individuals associated with pro-freedom movements. Sections 8A and 8C of the UAPA explicitly empower authorities to attach property deemed as “proceeds of unlawful activity” without requiring prior judicial approval (Bhat, 2021). The law grants investigative agencies the power to freeze assets, including homes, land, businesses and even political offices, solely based on administrative orders. In practice, these provisions are applied not to armed combatants, but to ordinary citizens, teachers, students, lawyers and traders, whose political views or familial affiliations are deemed threatening to state interests (Zia, 2019).

The result is a legal mechanism that converts dissent into a justification for property seizure. The Public Safety Act (PSA) 1978, while primarily a preventive detention law, also contributes to property repression indirectly. Sections 8 and 9 allow authorities to detain individuals without trial for up to two years,

with minimal judicial oversight (Rai, 2021). Once individuals are detained under the PSA, their properties are often frozen or attached under administrative orders, ostensibly as a security measure. In many cases, attachment extends to multiple properties of the same family, indicating a deliberate attempt to punish relatives and create broader economic vulnerability.

This intertwining of detention and property confiscation amplifies the coercive impact of PSA and makes it a multifaceted tool of repression (Whitehead, 2022). The Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) 1990, applied in “disturbed areas,” further empowers military personnel to take actions deemed necessary to maintain public order. Section 4(c) allows armed forces to destroy property during operations, ostensibly to counter insurgency (Bhat, 2021). In practice, AFSPA has been used to authorize the demolition of homes and other structures during alleged encounters or counter-terror operations. Bulldozer operations carried out under the Act often target not only suspected militants but also their families and communities. These demolitions are accompanied by police presence, ensuring compliance and preventing resistance and they serve as both punitive measures and a broader warning to the population (UN OHCHR, 2018).

It is essential to acknowledge the historical trajectory of India’s counter-terrorism framework. The Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA) 1985–1995, though lapsed, created a legal precedent for property confiscation, asset seizure and arbitrary detention in the name of counter-terrorism (Milanovic, 2020). Provisions of TADA, particularly those related to the attachment of property of accused individuals, have informed later statutes, including the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA) 2002 - 2004 and the amended UAPA framework. These laws share common elements: broad discretionary powers, minimal judicial oversight and provisions allowing for attachment or seizure of property without proof. By retaining this philosophy, India’s legal apparatus continues to prioritize state control over individual property rights in IIOJK (Veracini, 2015).

Beyond security laws, post-2019 amendments to Jammu & Kashmir land laws, Domicile Rules and development acts have significantly facilitated the appropriation of property by non-local actors while legitimizing the dispossession of locals. The repeal of Articles 370 and 35A removed historical restrictions that prevented non-residents from acquiring land in the region. Legal amendments, such as Sections 5 and 7 of the Domicile Rules 2020 and Sections 3(a) and 4(b) of the Jammu & Kashmir Development Act 2021, allow administrative authorities to classify occupied land as encroachment or unused, thereby enabling rapid attachment or demolition (Bhat, 2021).

These laws create a dual function: they not only legitimize the settlement of non-local actors but also provide administrative cover to confiscate the property of Kashmiris under technical pretexts. An example is the 2023 bulldozer campaign in Srinagar, where multiple properties in the HMT and Hyderpora areas were attached or demolished. Authorities cited alleged violations of land and development regulations, including encroachment on state land. However, these actions predominantly affected residents, while non- local or government-aligned individuals faced minimal enforcement. In this instance, UAPA was cited in conjunction with land law violations, demonstrating the intersection of security laws and property regulations to justify confiscation (Ghosh, 2022). These examples underscore how domestic laws have been adapted to consolidate control and enforce a pattern of repression.

Administrative Mechanisms

While domestic laws provide the legal authority, administrative machinery executes these policies on the ground. Agencies such as the National Investigation Agency (NIA), Special Investigation Agency (SIA) and Enforcement Directorate (ED) are central to initiating property seizures under UAPA and related statutes (Whitehead, 2022). These agencies identify properties allegedly linked to unlawful activities and coordinate with local authorities to enforce attachment or demolition orders. Once a property is flagged, police, revenue departments and municipal authorities are mobilized to operationalize seizures, often using bulldozers, locks, or administrative sealings to enforce compliance (Chowdhary, 2020).

Bulldozer operations have emerged as a symbolic and practical instrument of repression. Coordinated campaigns involve municipal officials, police and paramilitary units, deploying heavy machinery to demolish homes, offices and commercial properties (UN OHCHR, 2018). These operations frequently accompany the arrest or detention of property owners, ensuring that resistance is minimal. In several cases, political landmarks, such as the central office of Tehreek- e-Hurriyat Jammu and Kashmir, have been demolished, not only erasing property but also the political and historical identity associated with it.

Revenue departments play a crucial administrative role, issuing formal notices that transform executive orders into legally enforceable property attachments. Municipal authorities and local councils implement these , often citing anti-encroachment measures or urban development projects (Bhat, 2021). By framing confiscation within bureaucratic procedures, authorities create a veneer of legality, obscuring the punitive or politically motivated nature of the operations. The use of administrative discretion ensures efficiency and expediency, while simultaneously generating fear and compliance among local populations (Zia, 2019).

Examples of administrative coordination include the September–October 2025 property seizures in Baramulla, Shopian and Srinagar. In these cases, UAPA was invoked administratively to attach multiple properties belonging to individuals accused of supporting pro-freedom movements (Ghosh, 2022).

Notices were issued without hearings or judicial Patterns of Property Seizure and Confiscation7 oversight and demolition or freezing of property was carried out swiftly by municipal authorities with police support. These operations demonstrate how domestic law and administrative mechanisms work in tandem to execute systematic property repression.

Legal Loopholes and Arbitrary Practices

The domestic legal framework in IIOJK is riddled with loopholes and discretionary provisions that facilitate arbitrary property seizure. Broad statutory language in UAPA, PSA and AFSPA grants authorities sweeping powers without clear standards of evidence (OHCHR, 2022). For instance, UAPA allows attachment based on administrative suspicion rather than judicially verified evidence. AFSPA permits the destruction of property based on military discretion, while PSA facilitates property freezing through detention. This ambiguity allows authorities to target individuals based on political affiliation, family ties, or historical cases, rather than concrete violations (International Commission of Jurists, 2022).

Procedural safeguards are often absent. Property owners are frequently denied prior notice, explanation, or opportunity for hearing. Even where legal recourse exists, courts are either slow or reluctant to intervene due to the invocation of security concerns (Human Rights Law Network, 2023). The lack of transparency in administrative orders allows authorities to reuse old cases as justification for new confiscations (Voice of Victims Report, 2023). Properties implicated in prior investigations, regardless of their current legal status, are attached, sealed, or demolished. This practice orecycling legal documents ensures a continuous pattern of harassment while maintaining an appearance of legality.

Another dimension of arbitrary practice is collective or bloodline targeting. Family members of accused individuals, often unrelated to any alleged offenses, face property attachment or demolition (OHCHR, 2022). Political or social affiliations alone can render properties liable for seizure. Offices, educational

institutions, or even ancestral homes have been targeted because of the affiliations of relatives (Institute of Voice of Victims, 2023). This systemic approach transforms property into a tool of psychological coercion, economic marginalization and political control (Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, 2021).

The 2025 attachment of Nazir Ahmad Ganie’s ancestral home in Palpora, Kralgund, explains this mechanism. Authorities cited his residence in Azad Jammu and Kashmir as grounds for attachment under UAPA, even though he was not personally implicated in any unlawful activity (Voice of Victims Report, 2025). Similarly, the two-storey residence of Ghulam Mohammad Sheikh in HMT, Srinagar, was confiscated because of alleged online activity by his son. These examples highlight how domestic laws and administrative discretion combine to target families collectively, bypassing conventional standards of evidence or due process.

Finally, amendments to land and domicile rules have expanded these arbitrary practices. Sections 5 and 7 of the Domicile Rules and Sections 3(a) and 4(b) of the Development Act allow authorities to classify occupied property as encroachment, abandoned, or otherwise violative of regulations (Government of Jammu & Kashmir, 2020). These provisions, when coupled with UAPA and PSA, give authorities the power to attach or demolish property with minimal procedural oversight. The convergence of statutory ambiguity, administrative discretion and selective enforcement ensures that property repression remains continuous, systematic and effectively unchallengeable (Human Rights Watch, 2021).

The legal and administrative framework in IIOJK forms a cohesive mechanism for property repression. Domestic laws, including the UAPA, PSA, AFSPA and amendments to land and domicile regulations, provide the statutory authority for attachment, demolition and seizure of property. Administrative mechanisms operationalize these laws, deploying agencies such as NIA, SIA, ED, police and municipal authorities to enforce compliance. Legal loopholes, discretionary powers and the practice of recycling old cases ensure that property repression can be executed systematically and with minimal accountability. Through this framework, ordinary homes, ancestral lands, political offices and businesses are transformed into instruments of control, economic marginalization and psychological coercion.

PATTERNS OF PROPERTY CONFISCATION AND ATTACHMENT

Property confiscation and attachment in IIOJK after 5 August 2019 have assumed the character of a systematic governance practice rather than an exceptional legal measure. What is unfolding is not a random misuse of state authority but a structured political strategy that weaponizes civilian property to regulate behavior, discipline dissent and destabilize social foundations (Institute of Voice of Victims, 2023). Confiscation has shifted from being an ancillary security tool to a central pillar of internal control. Through selective targeting of civilians, coercive attachment procedures and the political use of property seizure against resistance-linked spaces and families, the state has converted ownership itself into a conditional privilege tied to political obedience (Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, 2021).

This transformation reflects a deeper shift in India’s Kashmir policy from conflict containment toward population control through economic and social coercion. From a human rights lens, it represents the institutionalization of collective punishment as a governing norm (International Commission of Jurists,

2022).

Targeting Civilians

One of the most disturbing features of the post-2019 confiscation regime is the deliberate expansion of targets beyond armed or politically active actors to encompass ordinary civilians whose social roles give them influence within their communities. Teachers, lawyers, traders, students, journalists, doctors and small business owners have emerged as the primary civilian class subjected to property seizures (Voice of Victims Report, 2025). This shift is neither accidental nor incidental. It reflects a calculated strategy aimed at dismantling the social infrastructure that sustains Kashmiri civic life. Each of these civilian categories holds structural

significance. Teachers shape intellectual consciousness. Lawyers defend detainees and challenge state narratives. Traders sustain economic circulation. Doctors ensure community survival. Students represent the future political imagination. Targeting these economic segments strategically weakens core social pillars while avoiding the visibility and international alarm that mass political arrests typically provoke. Property confiscation thus becomes a silent method of neutralizing influence without the spectacle of incarceration (Human Rights Law Network, 2023).

Official disclosures and verified local reports indicate that between 2019 and early 2025, more than 1081 properties were formally attached, seized or damaged across Srinagar, Baramulla, Shopian, Anantnag, Pulwama, Budgam, Bandipora and Kupwara. A significant proportion of these cases involved civilians with no proven militant involvement. Shopkeepers were accused of “indirect funding,” students of “digital association,” lawyers of “legal facilitation,” and doctors of “network linkages” (Voice of Victims Report, 2025).

In most instances, no convictions followed. Yet the property remained sealed, frozen, or confiscated. This pattern demonstrates that confiscation is no longer reactive to proven criminality. It is anticipatory and pre- emptive. Individuals are penalized not for what courts have established but for what security agencies assert. The presumption guiding these seizures is not guilt after trial but suspicion as sufficient ground for economic annihilation.

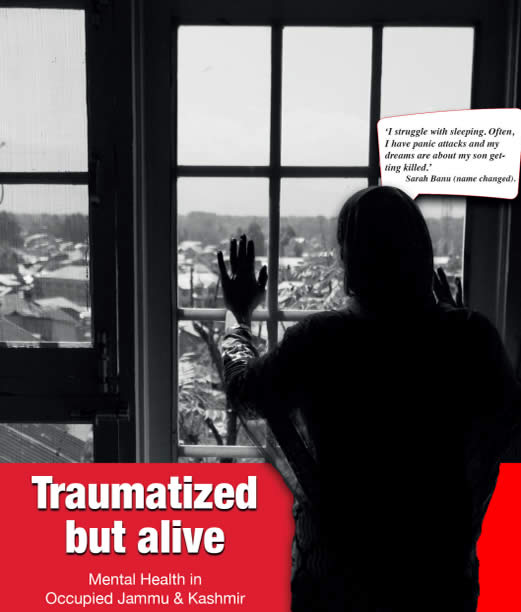

The result is a deepening architecture of collective punishment. Families lose homes for allegations leveled against one member. A trader’s entire warehouse may be sealed because a relative is accused of ideological sympathy. A teacher’s ancestral home may be confiscated due to a son’s political expression abroad. The punishment radiates outward from the individual into the family unit, transforming households into objects of security management (Human Rights Law Network, 2023).

This pattern erodes the boundary between personal accountability and inherited liability. Property confiscation no longer operates on individual responsibility. It is distributed across kinship lines. This transforms economic existence itself into a site of political vulnerability (Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, 2021). This produces what can be termed deterrence through deprivation. The objective is not merely to penalize but to induce anticipatory self- censorship. When communities witness respected civilians stripped of property without conviction, fear replaces dissent. Silence becomes economically rational (OHCHR, 2022).

Attachment Procedures

Property attachment in IIOJK operates through a procedural architecture that systematically shifts the burden of proof onto the accused and their families. Once a property is labeled as “proceeds of unlawful activity” or “terror-linked,” the presumption of illegality becomes entrenched by administrative decree rather than judicial determination. The owner does not receive prior notice in most cases. The sealing often follows surprise raids, after which families are informed that legal remedies remain open (Voice of Victims Report, 2025). In reality, access to remedy becomes structurally obstructed.

The key feature of this mechanism is the reversal of the evidentiary burden. Instead of the state being required to prove that the property is linked to crime, the owner is forced to demonstrate innocence, often under impossible conditions. Documentation is demanded for assets acquired decades earlier. Financial trails are reconstructed retrospectively. Transactions that predate current laws are reassessed under new security logics.

This procedural inversion transforms attachment into an autonomous form of punishment rather than a prelude to adjudication. For many families, the legal struggle becomes economically untenable. Lawyers’ fees, court travel, repeated hearings and bureaucratic delays drain already frozen resources (OHCHR, 2022). In this sense, the process itself becomes the sentence.

The data reflects this punitive architecture. Of the attachments initiated between 2022 and 2024, a large majority remained unresolved in courts by early 2025. Properties continued to stay sealed despite the absence of convictions. Businesses collapsed. Orchards went untended. Tenants were evicted. Livelihoods were irreversibly damaged long before any judicial clarity emerged (Voice of Victims Report, 2025). Moreover, once an attachment order is passed, financial institutions often freeze linked accounts automatically.

This collapses the family’s ability to pay legal expenses, school fees, medical costs, or even daily subsistence (Institute of Voice of Victims, 2023). The procedure thus creates a self-reinforcing cycle of immobility, where economic paralysis prevents effective legal challenge. What is especially troubling is the discretionary nature of these operations. Different families accused under similar allegations experience different outcomes depending on district administrations, agency involvement, or media attention. Such administrative selectivity strips attachment of even procedural neutrality.

This procedural design violates the foundational principle that punishment must follow proof. It also reflects techniques of coercive compliance, where governance is enforced through economic incapacitation rather than political legitimacy (OHCHR, 2022).

Property as a Tool of Political Repression

Beyond individual civilian targeting and procedural coercion, property confiscation in IIOJK has been systematically deployed to dismantle political infrastructure and extinguish organized dissent. Political offices, community welfare institutions, legal aid centers, media-linked spaces and resistance-associated buildings have been sealed or confiscated under broad security allegations.

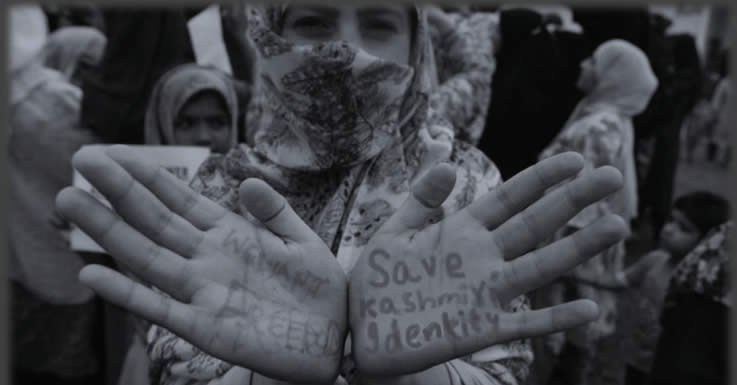

This weaponization of property transforms physical space into an instrument of ideological eradication.The confiscation of Hurriyat-linked offices across Srinagar and allied districts shows this pattern with particular clarity. These spaces were not mere administrative rooms. They functioned as sites of consultation, legal advocacy, public representation, documentation and collective memory (KashmiCoalition of Civil Society, 2021). Their sealing did not merely halt ongoing activity. It erased decades of organizational continuity.

Political repression through property also carries symbolic violence. When an office is confiscated, the act is not only administrative. It communicates that political presence itself is illegitimate. When a landmark is seized, the erasure becomes spatial and psychological. The city is rewritten into a landscape of obedience. This practice extends beyond organizations to families linked by kinship. The doctrine of punishment by bloodline has become one of the most chilling features of post-2019 confiscation policy. Properties are seized not because the owner is accused, but because a relative is accused (Human Rights Watch, 2021).

Parents lose homes because their sons live abroad. Sisters lose inheritance because brothers are alleged to be politically active. Political suspicion now travels genealogically. This form of repression restructures the family itself into a site of surveillance. Families are pressured to issue public disassociations. Kinship becomes securitized. Blood relations turn into legal vulnerabilities (Bhat, 2022). The message is unmistakable: political deviation carries consequences for the entire lineage. This reflects a move toward biopolitical governance, where not only individuals but family units are regulated as security variables (Agamben, 1998). From an IR lens, it mirrors internal colonial systems where collective identities are managed through inherited punishment.

Strategic Logic of Property Repression

The use of property confiscation in IIOJK follows a discernible strategic logic:

• Economic deterrence of dissent: It converts political dissent into economic risk. By making dissent materially costly, the state shifts resistance from a moral to a survival calculation.

• Restructuring social leadership: When lawyers, teachers and traders are economically disempowered, community leadership fragments. Organized resistance becomes harder to sustain.

• Dissolution of political memory: Through the confiscation of offices and landmarks, entire histories of mobilization are removed from public space.

• Population discipline without mass arrests: Economic fear suppresses activism more quietly and more efficiently than prisons.

This logic reflects what population-centric control theorists describe as compliance engineering. The aim is not ideological persuasion. It is behavioral pacification through structural vulnerability (Foucault, 1977). Broader Economic and Social Consequences The ripple effects of property confiscation extend

far beyond the immediate families targeted. Traders losing warehouses disrupt supply chains. Orchard seizures interrupt seasonal labor cycles. Shop closures reduce local employment. The cumulative effect is distributive economic contraction within already fragile civilian markets (Human Rights Law Network, 2023). This contraction deepens debt dependency. Families turn to informal lenders. Assets are sold at distressed prices. Youth enter precarious wage labor. Education becomes unaffordable. Migration becomes necessary. Political repression thus converts directly into economic displacement. This process weakens collective capacity for sustained political mobilization.

Communities locked in survival economies lack the institution alenergy required for organized resistance. In this way, confiscation policy achieves what mass incarceration cannot: long-term political exhaustion (Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, 2021) The patterns of property confiscation and attachment in IIOJK reveal a consolidated architecture of political control grounded in civilian economic punishment rather than judicial accountability. Through the strategic targeting of socially influential civilians, coercive attachment procedures that reverse the burden of proof and the overt political use of property seizure against resistance-linked spaces and families, ownership itself has been transformed into a conditional privilege dependent on political obedience.

This reflects an internal colonial mode of governance where civilian economies and family structures become instruments of domination. And also signifies the normalization of collective punishment through administrative means. Property in IIOJK is no longer a protected civilian space. It has become a frontline weapon of state repression.

DEMOLITIONS AND BULLDOZER POLICY

Demolition in IIOJK has ceased to function as a regulatory tool and has instead matured into an organized instrument of political punishment. The bulldozer is no longer used primarily to clear space for infrastructure or enforce municipal order. It is now deployed to discipline, intimidate and economically devastate communities marked as politically suspect, a trend documented in studies examining punitive urban governance in conflict zones (Gayer & Jaffrelot, 2021). This transformation is not accidental. It reflects a broader reorientation of state power in Kashmir from security management to punitive population control. The target is not merely alleged offenders. The target is the social environment that sustains dissent.

After 5 August 2019, demolitions have become inseparable from the counter-resistance strategy. They operate alongside arrests, surveillance and property attachment, but they perform a distinct function. An arrest incapacitates an individual. Demolition terrorizes a community. It converts punishment from an individual experience into a collective spectacle. The rubble becomes the message. Fear becomes the policy outcome (Human Rights Watch, 2022).

Use of Demolitions as Punitive Measures

In IIOJK,demolitions are increasingly used as a form of retaliation after incidents rather than as necessary emergency responses. Houses, shops, orchards and offices are routinely destroyed following alleged encounters or arrests. The timing alone reveals the intent. Destruction doesn’t happen during conflict; it happens after the state has established control. The demolition isn’t reactive; it’s meant to send a message. Scholars have noted that such post-incident punitive demolitions align with frameworks of collective retaliation, often used to discipline populations under securitized governance (Ganor & Braun, 2017).

This reveals a fundamental shift in governance logic. The house is not demolished because it poses an immediate threat. It is demolished because someone associated with it allegedly did. This distinction is crucial. It transforms demolition from a security response into collective punishment, a practice explicitly prohibited under international humanitarian law (ICRC, 2016). The family home becomes hostage to the political conduct of one member. This collapses the legal boundary between individual responsibility and familial liability. Since 2019, dozens of residential structures belonging to families of protest-linked youth have been demolished across districts such as Pulwama, Shopian, Anantnag, Image: Amnesty International

Patterns of Property Seizure and Confiscation13 Kulgam, Baramulla and Srinagar. In many cases, no recovery of weapons occurred from these homes at the time of demolition. The accused individual had already been killed or detained. The justification was never an immediate tactical necessity. It was punitive signaling. Shops and commercial establishments have also been targeted following political incidents. Markets that served entire neighborhoods were flattened after localized unrest. These were not random structures. They were economic lifelines. Their destruction produced instant unemployment, debt and long-term business paralysis. Research on economic repression notes that such policies deliberately erode community resilience and deepen dependency (Ahmad, 2020).

Orchards, which represent generational wealth in Kashmir’s agrarian economy, have not been spared. Apple orchards belonging to families of accused youth have been cut down or bulldozed under various pretexts. This form of punishment strikes at inherited economic security. A demolished house destroys shelter. A destroyed orchard destroys future income across decades. This is economic incapacitation by design. Offices have also been razed under the same punitive framework. Politically linked offices, welfare-associated spaces and meeting points of community organizations are bulldozed under vague claims of illegality. Their destruction removes not only physical infrastructure but also institutional memory and organizational continuity.

The space for collective gathering shrinks along with physical walls. The choice of demolition as punishment is deliberate. It achieves multiple objectives simultaneously. It humiliates families in public. It economically paralyzes dependents. It sends a warning to neighbors. It visually demonstrates state dominance. It also avoids the procedural scrutiny that long trials attract. Bulldozer justice is instant, irreversible and spectacular. What makes this strategy especially coercive is that it violates the basic principle of proportionality. Even if one assumes the guilt of an accused person, the destruction of an entire household far exceeds any reasonable punitive standard. This excess is the point. The disproportion is meant to intimidate not only the family but the wider political environment (UN Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing, 2021).

Bulldozer Operations

Bulldozer operations in IIOJK are not isolated municipal actions. They are heavily securitized exercises. Police, armed forces, district officials and sometimes special units accompany these demolitions. Entire areas are cordoned off before the machine arrives. Communication networks are often restricted. Media access is controlled. The operation resembles a military maneuver more than a civil enforcement act. The presence of armed personnel serves two purposes. It prevents physical resistance. It also stages power. Residents are not merely evicted. They are overpowered. The demolition becomes an enforced submission rather than an administrative process. This echoes what scholars describe as “performative state violence,” where force is enacted visibly to cultivate obedience (Johansen, 2020).

Families are frequently given minutes to evacuate. Personal belongings are buried under debris. Livestock, household goods, commercial stock, school materials and essential documents are destroyed. There is no inventory process. There is no transparent valuation. There is no assured compensation. The immediacy of loss intensifies trauma and disorientation. The bulldozer also functions as a moving threat. The sound of the machine approaching generates panic not only in the targeted household but across entire neighborhoods. Streets empty. Windows close. Children hide. Communities freeze. This collective fear response is not incidental. It is produced by repetition. When demolitions occur again and again, the machine becomes a symbol of unpredictable punishment.

The operations are often filmed. Visual footage circulates on social media and national news platforms. The collision of steel with stone becomes a spectacle of power. This serves two audiences. Locally, it teaches submission. Nationally, it reinforces a narrative of “strong state action.” The human cost remains largely invisible in the dominant discourse. This model closely mirrors bulldozer deployments against Muslim neighborhoods in other parts of India. In Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Delhi and Haryana, Muslim homes and shops have been demolished after communal unrest. In many of these cases, demolitions followed allegations but preceded convictions (Amnesty International, 2022). The pattern is consistent. Arrest the accused. Bulldoze the neighborhood. Broadcast the destruction.

This reveals that Kashmir is not an exception. It is part of a broader ideological governance framework where the bulldozer is normalized as a parallel justice system. The difference is that in IIOJK, this weapon is more deeply integrated into counterinsurgency logic. What appears as communal repression in mainland India operates as an occupation policy in IIOJK. The administrative choreography of these operations further exposes intent. Revenue officials mark the site. Engineers prepare the machinery. Police seal access routes. Media teams arrive. The demolition unfolds like a rehearsed performance. This level of coordination is incompatible with the claim that these are spontaneous law enforcement necessities. They are planned interventions.

Bulldozer operations also have a gendered impact. Women face displacement without an alternative shelter. Household economies collapse overnight. Care responsibilities multiply under crisis conditions. Yet women are rarely consulted or compensated. The state communicates with the bulldozer, not with the displaced (UN Women, 2020). Children experience some of the deepest psychological scars. Schools are interrupted. Study materials are destroyed. Safety is shattered. The home, which anchors childhood stability, becomes a site of terror. Fear becomes normalized early. This is how repression reproduces itself across generations.

Narrative Justifications

The most dangerous feature of the demolition policy in IIOJK is not the machine itself. It is the narrative that legitimizes it. Demolitions are rarely presented as punishment. They are framed as “lawful enforcement.” The most common justifications are counter-terrorism necessity, anti-encroachment drives, urban development, road expansion and tourism infrastructure.

This rhetorical strategy performs an important political function. It masks repression as regulation. It transforms dispossession into development. The victim is reframed as an illegal occupant. The punishment is reframed as an administrative correction. The state is reimagined as a neutral enforcer rather than a coercive ruler. The “anti-encroachment” narrative is especially potent. Under this label, homes that have existed for decades are suddenly declared illegal. Land records are selectively interpreted. Customary possession is erased. Entire civilian settlements are transformed rhetorically intocriminal anomalies (Ramanathan, 2022).

Once branded as encroachers, residents lose the moral standing of citizens. Their displacement becomes bureaucratically acceptable. Urban development and infrastructure expansion provide another powerful justification. Highways, tourist corridors and beautification drives are used to erase roadside shops, residential clusters and traditional market zones. The narrative speaks of progress. The reality is displacement without rehabilitation. Tourism has emerged as one of the most effective covers for demolition. Riverfront projects, lakefront beautification, resort development and eco-tourism zones justify large-scale evictions. Indigenous dwellers become aesthetic obstacles. Their removal is framed as an environmental necessity. Meanwhile, elite tourism Patterns of Property Seizure and Confiscation15 infrastructure expands in the same spaces once locals are cleared. This narrative inversion is not accidental.

It converts indigenous presence into an environmental threat and external investment into ecological salvation. It allows dispossession to be defended using the language of sustainability and prosperity. A further ideological layer is added through the communal framing of “land jihad” or “illegal Muslim occupation.” This rhetoric, widely circulated in right-wing political discourse in India, casts Muslim landholding itself as suspect. When bulldozers then target Muslim neighborhoods, the destruction is read not as injustice but as cultural retaliation.

This same language has been used to justify demolitions in Delhi’s Jahangirpuri, parts of Gujarat, Haryana’s Nuh region and across Uttar Pradesh. After communal violence, Muslim homes and shops were singled out for destruction under the claim of removing illegal structures. No serious effort was made to apply the same standard evenly across communities. This pattern reveals that demolition is not merely a governance tool. It is an ideological weapon. It marks certain bodies as disposable. It marks certain homes as illegitimate. It transforms citizenship into a conditional status dependent on political conformity and communal identity.

In IIOJK, where identity is already securitized, this ideological framing is amplified further. The Kashmiri Muslim is not only framed as an encroacher but also as a permanent security suspect. The bulldozer thus becomes the ideal instrument. It destroys while appearing to regulate. It punishes while claiming to develop. It intimidates while performing legality. Demolitions and bulldozer operations are not peripheral excesses of governance. They are central instruments of political control. They convert private life into a terrain of punishment. They transform economic survival into a conditional privilege. They erase not only buildings but the possibility of security itself.

Through the selective use of demolitions as punitive measures, the state enforces collective responsibility for alleged political acts. Through aggressive bulldozer operations backed by armed force, it manufactures public fear and submission. Through layered narrative justifications of security, development and anti-encroachment, it disguises dispossession as legality. The linkage between Kashmir and the wider bulldozer politics across India reveals that this is not a localized aberration. It is a normalized model of coercive governance, deployed most fiercely against Muslims. What differs in Kashmir is not the method but the intensity and strategic integration of this method into counter-resistance doctrine. The bulldozer does not merely clear land. It clears memory, livelihood, dignity and belonging. It turns the home into a crime scene. It turns development into displacement. It turns legality into spectacle. In doing so, it reveals a central truth: in IIOJK, demolition has become governance by destruction.

LAND SEIZURES AND STRATEGIC PROPERTY APPROPRIATION

Land in IIOJK is no longer governed as a protected civilian resource. Since 5 August 2019, it has been reclassified as a strategic asset to be reallocated for military consolidation, investor-driven urban restructuring and long-term demographic transformation (Bose, 2021). The seizure of land is not episodic. It is systematic. It is not reactive. It is developmental in language and colonial in intent. What is unfolding is not merely a redistribution of land. It is a political reengineering of territory through law, planning and executive power (Junaid, 2020). Unlike overt demolitions, land seizures operate through quieter mechanisms. Files move through revenue offices. Notifications appear without prior consultation. Classifications change from “agricultural” to “strategic.” Ownership is displaced not through spectacle but through bureaucratic finality. This makes land appropriation one of the most dangerous instruments of power in IIOJK. It functions without public visibility but with irreversible

consequences.

Land is not only space, it is power, sovereignty and identity. Control over land determines who stays, who leaves, who profits and who disappears (Yiftachel, 2006). In Kashmir, land seizures are now the architecture upon which military entrenchment, settler infrastructure and demographic engineering are being constructed.

Military and Security Expansion

One of the most aggressive patterns of land seizure in post-2019 IIOJK is the designation of civilian and ecologically sensitive zones as “strategic land.” This category allows the state to bypass civilian consent, environmental safeguards and provincial protections. Once land is declared strategic, it is automatically removed from public scrutiny. The logic of national security overrides all competing claims. Tourist and ecological zones such as Gulmarg, Sonmarg, Pahalgam and large tracts of Kupwara and Bandipora have been brought under this classification. These areas are not conflict frontlines. They are economic lifelines for local communities dependent on tourism, pastoralism and seasonal trade. Yet they are now increasingly absorbed into military infrastructure.

In Gulmarg alone, more than 1,000 kanals of forest and pasture land have been appropriated for military firing ranges, training areas and restricted movement zones. In Sonmarg, over 300 kanals of land have been transferred for army use, despite the area’s status as an eco-sensitive tourism corridor. These transfers were executed through executive notifications, not legislative debate (Crisis Group, 2020). What makes this appropriation uniquely coercive is that these lands were not abandoned. They were actively used by shepherds, seasonal workers, pony owners, tourism porters and orchardists. The seizure did not merely displace families. It dismantled entire micro- economies. Seasonal grazing cycles collapsed.

Tourism

income shrank. Intergenerational livelihoods vanished. New border infrastructure has also accelerated land appropriation. Villages along the Line of Control and International Border have witnessed continuous land absorption for bunkers, fencing systems, barracks, forward posts and new road networks designed solely for military mobility. Farmers lose access to their own fields due to buffer zones. Movement is restricted. Cultivation becomes unviable. Dispossession is achieved not through eviction but through functional denial. The argument that these seizures are purely defensive collapses under scrutiny. Many appropriated zones lie far from active infiltration routes. Their value is not tactical. It is territorial. The objective is not simply to defend borders. It is to permanently militarize space so that civilian recovery becomes structurally impossible (Duschinski & Mahmood, 2021).

Once land is militarized, it rarely returns to civilian use. Temporary occupation becomes permanent absorption. Over time, entire regions are transformed into security corridors where civilian presence is tolerated only under surveillance. This is not short-term counterinsurgency. It is long-term spatial domination. The seizure of ecologically sensitive land serves an additional function. It prevents the return of displaced populations. It blocks local economic revival. It ensures that strategic heights, valleys and corridors remain permanently outside civilian authority. Land becomes a silent weapon of territorial immobilization.

Urban Transformation Projects

If military expansion represents the hard face of land Sainik Colony. Image: Free Press Kashmir Patterns of Property Seizure and Confiscation17 seizure, urban transformation represents its soft face. Since 2019, large-scale redevelopment schemes in Srinagar, Jammu and emerging urban corridors have been used to structurally reallocate land ownership. The most significant of these is the Srinagar Master Plan 2035, along with riverfront redevelopment, smart city projects, tourism corridors and Special Investment Zones (Rehman, 2022).

On paper, these projects promise modernization, infrastructure efficiency and economic growth. On the ground, they produce mass land dispossession and ownership transfer. Residential clusters, commercial neighborhoods and agricultural belts are reclassified for public use, acquisition, or redevelopment. The process follows a consistent pattern: notification first, compensation uncertainty next, displacement inevitable. Under the Special Investment Zones, thousands of kanals of land across Kashmir are being identified for industrial parks, tech corridors, logistics warehouses and mass housing developers. These zones are framed as engines of growth. Yet ownership patterns reveal a different truth. Land is being transferred away from local agrarian and residential communities toward corporate developers and non-local investors.

While official narratives speak of employment creation, there is no proportional protection for local ownership. A Kashmiri farmer does not become an industrial shareholder. He becomes a displaced laborer. The ownership of land shifts outward. The wage dependency of locals increases inward. The mass housing projects further illustrate this logic. New townships promoted as “affordable housing” are legally structured in ways that allow non-local buyers unrestricted access. Local Kashmiris, already economically strained by years of conflict and lockdowns, are unable to compete in these markets. Property ownership thus migrates demographically even when physical displacement is not immediate (Chatterji, 2023).

This is not organic urban evolution. It is a state- structured land transfer disguised as development. The disproportionate impact on Kashmiris is not accidental. It is the mechanism through which demographic and economic power is rearranged. Urban land seizures also extend to riverbanks, wetlands and peri-urban agricultural belts. Entire riverfront communities have lost land under redevelopment banners. Wetland areas once used by fishing communities have been reclaimed for commercial projects. Each environmental justification conveniently aligns with commercial interest once civilian presence is eliminated. The critical pattern is this: Kashmiris lose use-rights first, title next and finally cultural attachment. Urban transformation does not merely displace bodies. It displaces belonging.

Demographic Engineering

Since 2019, a series of legal transformations have fundamentally altered who can own land, who can settle permanently and who has a political stake in the territory. New domicile regulations have granted residency rights to millions of non-locals, including government employees, security personnel, families and external investors. Once domicile is secured, land ownership becomes legally accessible. This creates a structural pipeline between legal inclusion and territorial control (Singh, 2022). Before 2019, land ownership in Jammu and Kashmirwas restricted to permanent residents. That barrier is now dismantled. The consequence is not abstract. It is measurable. Thousands of non-locals have already applied for and received land documents. New housing colonies are explicitly marketed to external populations. Land becomes the conduit through which demographic balance is re-engineered. The long-term political objective is clear. Ownership determines electoral weight, economic dominance and cultural permanence.

Once a critical mass of land shifts into non-local control, political power inevitably follows. Indigenous political agency weakens not through formal disenfranchisement but through territorial dilution (Varshney, 2021). Demographic engineering through land operates slowly but irreversibly. A demolished home may be rebuilt. A confiscated shop may be reclaimed. But once land titles shift across communities, the transformation becomes permanent. Territory is the final currency of power.

The weakening of Kashmiri ownership is not merely economic. It is civilizational. Land carries memory, ancestry, burial grounds, shrines and oral history. When ownership changes, cultural continuity fractures. The population may remain physically present, but its relationship to place becomes precarious. This is why large tracts of land are now being systematically removed from local control, even in areas untouched by conflict. The goal is not only to suppress resistance today. It is to pre-empt resistance tomorrow by dissolving the territorial basis of collective identity.

From a settler-colonial lens, this is a textbook strategy. First, legal barriers to external settlement are removed. Second, military infrastructure secures space. Third, urban development restructures property markets. Finally, indigenous ownership becomes statistically marginal. Political subordination then becomes demographic fact (Wolfe, 2006). Land seizure in IIOJK is not a by-product of security policy. It is the central mechanism through which territorial power is being consolidated after 2019. Through the strategic designation of land for military expansion, the aggressive restructuring of urban property regimes and the legal facilitation of settler ownership, Kashmir is being transformed not only politically but spatially. Unlike demolitions that shock through visibility or confiscations that punish through legality, land seizures operate through permanence.

Once land is lost, recovery becomes structurally near-impossible. This makes strategic property appropriation the most enduring weapon in the architecture of repression. The battlefield in IIOJK is no longer only fought through arrests or encounters. It is being redrawn through land records, zoning maps, investment corridors and township blueprints. The future of IIOJK is being decided not only by force but by files. And in that future, the most decisive question will not be who resists but who owns the land on which resistance once stood

CASE STUDIES

Post-Pahalgam Crackdown:Civilian Homes as the New Battleground

After the manufactured incident of Pahalgam, Indian authorities rapidly reframed the region’s political landscape under the guise of “anti-terror sanitisation” and “pre-emptive security action.” These terms became the state’s newest justification for widespread seizures, attachments and bulldozer-driven demolitions, actions overwhelmingly targeting ordinary Kashmiri civilians with no proven link to any security case. What unfolded was not counterterrorism, but a systematic project of collective punishment engineered through the

weaponization of property (Hindustan Times, 27 Apr 2025). In the immediate days following Pahalgam, Indian forces launched a demolition drive that made one fact unmistakably clear: the collective, not the individual, has become the intended target of state retaliation. On 27 April 2025, the two-storey home of Adil Thoker in Guree village was blown apart in a controlled explosion, leaving only a damaged kitchen standing. Neighbors were forcibly moved nearly a hundred meters away and Thoker’s father, brother and cousins were detained, despite no evidence linking them to the incident. The purpose was not to neutralize a threat; it was to send a message that an entire family, an entire neighbourhood, can be punished for the alleged acts of one individual.

This same logic was violently replicated across Pulwama. In the early hours of 25 April 2025, the family home of Asif Sheikh was destroyed after forces locked livestock inside sheds, ordered residents to cover their ears and detonated explosives that tore apart the doors, windows and internal structure of the house. This was not a rapid- response security action, it was a pre-planned punitive strike. In Murran, the home of Ahsan Ul Haq Sheikh was blown up on the night of 26 April 2025, causing structural damage to surrounding houses and terrifying residents.

Neighbours described witnessing two massive blasts that “felt like everything was over.” Villagers later confirmed to journalists that the operation was carried out by Indian forces, a claim echoed publicly by local MP, despite the government’s continued silence (Hindustan Times, 27 Apr 2025). These documented cases expose the core of the post- Pahalgam strategy: convert suspicion into structural violence. The doctrine of punishment by bloodline, already visible in earlier years when parents lost homes because sons lived abroad, or sisters were denied inheritance because brothers were accused of political activity, has now accelerated. The state increasingly treats kinship itself as a security liability. The result is a chilling form of genealogical criminalization where the burden of accusation is imposed on entire family networks.

Parallel to these punitive demolitions, the state has expanded its economic warfare on Kashmiri civilians. Orchard workers, traders, transporters, small shopkeepers and warehouse owners report receiving attachment notices under UAPA and CrPC provisions even when no FIR, investigation, or allegation exists against them. What qualifies a property for demolition today? A vague label: “potential staging point.” This term is broad enough to encompass any residential home, any field, any shop. It is a legal vacuum deliberately crafted to justify unlimited state interference. Patterns of Property Seizure and Confiscation19 This strategy is not new; it is an intensified continuation of earlier coercive measures. The seizures of civilian homes in HMT (2023), the Hyderpora attachments of November 2023 and the sealing of Hurriyat-linked offices across Srinagar in 2022–2024 laid the architecture of property-based repression. Under the post-Pahalgam narrative, these earlier actions are now being retroactively packaged as part of a coherent “security doctrine.”

In reality, they reveal a sustained escalation of authoritarian control masked as counterterrorism (Al Jazeera, 2025). The demolition campaign also serves a deeper political purpose. First, it disciplines political behaviour by tying dissent to economic destruction. A family that fears losing its home becomes a family that avoids political expression. Second, it dismantles community leadership. Lawyers, teachers, scholars, humanitarian workers and small business owners rely on physical spaces for instance offices, workshops, orchards, shops to sustain their role in society. Destroy those spaces and you destroy their capacity to lead.

Third, demolitions rewrite the physical and psychological landscape ofIIOJK. Flattened homes, razed welfare centres and confiscated offices erase community memory and impose a geography defined by fear, obedience and state supremacy. The repurposing of the Pahalgam incident as a blanket justification marks a decisive shift: counterterrorism has been transformed into a mechanism of population control. The everyday civilian is now the central target. Property, not weapons, has become the primary battlefield. The objective is not to neutralize threats but to engineer compliance, suppress identity and exhaust the political energies of Kashmiris.

India’s post-Pahalgam property repression is not an aberration, it is an assertion of absolute state power. It demonstrates a political project willing to manufacture pretexts, criminalize lineage, erase community spaces and collapse civilian economies in pursuit of dominance. And it makes clear that the struggle today in Kashmir is being fought not only through arrests or surveillance, but through the deliberate destruction of the civilian home. Demolished house of Adil Thoker in Guree village of South Kashmir. Bilal Kuchay/NPR

Red Fort Blast and Escalation of Property Repression

The Red Fort blast in Delhi did not inaugurate property repression against Kashmiris, but it dramatically accelerated it. What existed before as a coercive policy tool was reactivated with unprecedented speed, scale and secrecy after this single security incident. The blast became a national pretext, not merely for criminal investigations but for collective property punishment, expanded profiling and administrative confiscation across IIOJK and even outside it. This episode reveals how isolated security events are strategically converted into instruments of mass internal coercion (Buzan, Wæver, & de Wilde, 1998).

The Red Fort incident was not treated as a contained

criminal act. It was transformed into a political narrative of existential threat, allowing the state to justify measures that would otherwise face judicial and public resistance. In this transformation, property emerged as the most immediate and silent casualty. Confiscation became a symbolic response to demonstrate sovereignty, deterrence and punitive dominance over an entire community (Agamben, 2005). This case study exposes how security discourse, when weaponized, collapses the boundary between suspect and civilian, between investigation and punishment and between rule of law and rule by fear.

Pretextual Use of Security Incidents

The Red Fort blast did not occur in Kashmir. It occurred in Delhi. Yet its most severe property-related consequences unfolded inside IIOJK. This geographic displacement of punishment is itself politically revealing. The incident functioned less as a crime to be solved and more as a trigger event used to legitimize expanded coercive policies against Kashmiris as a collectivity (OHCHR, 2018).

Within weeks of the blast, Jammu and Kashmir police, aided by national agencies, publicly announced that property seizures would be intensified against those “suspected” of supporting militancy, online or offline. No judicial thresholds were established. No new statutes were passed. The escalation occurred entirely through administrative interpretation of existing powers. This reveals that the incident served not as a legal turning point but as a narrative accelerator (Fisher, 2020). Property confiscation moved from being episodic tobeing campaign-based. Police statements openly framed the escalation as part of a broader crackdown justified by national security.

The Red Fort blast was repeatedly cited as evidence of an expanding “terror ecosystem” with alleged roots in Kashmir. This rhetorical expansion allowed the state to stretch the scope of guilt far beyond the actual perpetrators (Chakravarti, 2021). The razed house of Ahsan Ul Haq Sheikh’s family house in Murran area of Pulwama district on April 26, 2025 Bilal Kuchay/NPR Patterns of Property Seizure and Confiscation21

This reflects a classic securitization spiral. A single incident is elevated into a civilizational threat. Exceptional measures are normalized. Property punishment becomes not a remedy but a message. The most dangerous consequence of this logic is that future incidents no longer need to occur in Kashmir to justify repression in Kashmir. The territory becomes permanently vulnerable to retaliatory governance based on events occurring anywhere in India.

Targeting Ordinary Citizens

One of the most disturbing shifts after the Red Fort blast was the rapid extension of property confiscation to ordinary civilians with no direct or proven involvement in any security activity. Students, teachers, shopkeepers, engineers, transport workers and even families of overseas Kashmiris were suddenly swept into the net of suspicion. This represented a decisive break from even the minimal pretense of individualized culpability. Property repression now operates through relational guilt, a pattern historically associated with collective punishment measures condemned under international law (Human Rights Watch, 2022).

Several documented cases following the blast involved:

• University students whose family homes were searched and threatened with sealing based purely on alleged online activity.

• Small traders whose shops were attached because they had once provided food supplies to someone later accused in a case.

• Families of Kashmiris working in the Gulf, whose properties were frozen on the claim that remittances constituted “suspicious financial movement.”The logic was not evidentiary. It was exemplary. Each case served as a warning to the wider population: no degree of social normalcy immunizes property from

state retaliation. This strategy deliberately collapses the private-public divide. Property, traditionally the last zone of personal security, is made directly contingent upon political obedience (Foucault, 1991). This is not counterterrorism. It is population discipline through economic fear.

Arbitrary Seizures and Administrative Secrecy

A defining feature of post-Red Fort property repression is its procedural opacity. Homes, offices and commercial establishments have been sealed without prior notice, without hearings and without meaningful opportunity for legal contestation, practices incompatible with basic due-process standards (UN Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing, 2021).

What makes this particularly alarming is the widespread recycling of old files. Many of the confiscations after the Red Fort blast were not based on new investigations. They were justified using years-old FIRs, dormant intelligence notes, or unresolved inquiry reports. The blast provided the narrative cover necessary to resurrect stale cases and convert suspicion into immediate economic punishment. This administrative secrecy creates a condition of permanent vulnerability. Any past interaction with law enforcement, regardless of outcome, can be retroactively converted into justification for present-day property seizure. Legal finality loses meaning. Time provides no protection.

This destroys the principle of legal certainty and institutionalizes fear as a governance tool (UN Human Rights Committee, 2019). Once property is seized, procedural barriers ensure prolonged deprivation. Appeals move slowly. Hearings are delayed. Documents are disputed. Meanwhile, families remain dispossessed. The process itself becomes the punishment. In effect, administrative secrecy converts property confiscation into a form of summary punishment without trial.

Broader Implications: Surveillance, Fear and

Manufactured Obedience

The most far-reaching consequence of the Red Fort–triggered escalation is the expansion of social surveillance. Property repression has become a mechanism through which communities are forced into self-policing behavior, an outcome consistent with broader theories of punitive governance under

securitized regimes (Zedner, 2009). Neighborhoods monitor one another. Families pressure their own members to avoid political expression. Silence becomes a survival strategy. This is no longer sporadic repression. It is a system of regulated obedience. The threat is always implicit: one accusation, one allegation, one online post, one disputed financial transaction and the home can be sealed. Property thus becomes a political hostage. Civilian compliance is no longer enforced only through arrest or detention. It is implemented through the constant possibility of dispossession.

The consequences are visible across social life in IIOJK:

• Citizens avoid public political expression not because they accept state legitimacy, but because they fear economic annihilation.

• Families discourage youth from education-driven political debates.

• Lawyers, journalists and professionals practice strategic self-censorship to avoid jeopardizing family assets.

• Even humanitarian activity is restrained due to fear of retrospective criminalization (Amnesty International, 2023).

This is not stability. It is manufactured calm built on economic terror. This represents a shift from coercive stabilization to compliance engineering. The objective is not to persuade or negotiate. It is to construct a society that remains outwardly passive because rebellion has become financially suicidal. This also collapses the distinction between punishment and prevention. People are punished not for what they have done, but for what the state fears they might do.

Red Fort as a Precedent, Not an Exception

The most dangerous legacy of the Red Fort episode is that it established a functional precedent. It demonstrated how rapidly property repression can be expanded using national security narratives. This precedent now permanently lowers the threshold for future escalations (Wilkinson, 2015).Any future security incident, anywhere in India, can now be rhetorically linked back to Kashmir and translated into fresh cycles of dispossession. The violence does not need to be physical. It only needs to be symbolic.

This creates what can be termed a permanent retaliatory regime, where Kashmiris remain structurally exposed to punishments triggered by events over which they have no control. The Red Fort blast did not merely coincide with an increase in property repression in IIOJK. It redefined the speed, scale and justification of that repression. It converted security discourse into a master key that unlocked faster confiscations, deeper surveillance, expanded profiling and normalized administrative secrecy. Ordinary civilians became primary targets. Property was transformed into a disciplinary device. Legal process was quietly displaced by executive urgency. Fear became a governance technique. And obedience became an economic necessity. This case study reveals a central truth: in IIOJK, property is no longer only an economic asset, it is a political instrument used to reorder loyalty, silence dissent and manufacture submission. The Red Fort blast was not used to deliver justice. It was used to expand power

PROPERTY CONFISCATION AND SEIZURE CASES DATE OF NEWS AREA VICTIM / PROPERTY OWNER PROPERTY DETAILS / WORTH

HUMAN RIGHTS AND INTERNATIONAL LEGAL IMPLICATIONS OF PROPERTY REPRESSION

The large-scale confiscation, attachment and demolition of property constitute a multi-layered violation of international human rights law, international humanitarian law and even India’s own constitutional and statutory framework. When examined through a legal lens, property repression in IIOJK reveals itself as a structured regime of arbitrary punishment, collective retribution and socio-economic warfare against a protected civilian population (International Commission of Jurists, 2022). These actions operate outside the boundaries of legality while being dressed in the language of law. The result is not security governance but institutionalized injustice.

Property has become a tool of coercion rather than a protected right. Confiscations are executed without convictions. Attachments proceed without adjudication. Demolitions occur without rehabilitation. These practices expose a deliberate inversion of legal order, where executive power substitutes judicial authority and suspicion replaces proof (Baxi, 2020). The architecture of justice is hollowed out while its outer shell is maintained for formal legitimacy. This section demonstrates that property repression in IIOJK is not only unlawful in isolated instances; it is structurally incompatible with the most basic principles of justice, legality and human dignity recognized under global legal norms.

Violations of Domestic and International Law Property repression in IIOJK also collapses under scrutiny of India’s own constitutional framework. Article 300A of the Constitution of India guarantees that no person shall be deprived of property except by authority of law. “Authority of law” requires not only a statutory basis but judicial supervision and procedural fairness. Executive discretion alone does not satisfy this constitutional threshold (Singh, 2017). In IIOJK, however, homes are sealed through police notices, revenue attachments and district magistrate orders without any prior judicial determination. This practice dilutes constitutional protection into administrative convenience. It converts preventive power into punitive authority.

Several domestic statutes are repeatedly misused to facilitate this repression. These include the UAPA, the Code of Criminal Procedure and the Jammu and Kashmir PSA. None of these laws authorizes punitive confiscation of family property without conviction. Yet they are routinely cited to legitimize attachments. This reflects not lawful enforcement but executive overreach (Aiyar, 2022). The state is acting beyond its lawful powers. Property confiscation thus becomes not law enforcement but constitutional subversion. The right to property is universally recognized as a foundational human right under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which affirms under Article 17 that every person has the right to own property individually and collectively and that no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of it. The central legal prohibition here is not deprivation itself but arbitrariness (UDHR, 1948). Deprivation becomes unlawful when it lacks due process, proportionality and judicial oversight. Property repression in IIOJK meets every legal indicator of arbitrariness simultaneously.

First, there is a systematic absence of prior judicial adjudication. Families frequently discover their homes sealed through police notices, administrative boards, or revenue orders without any preceding court hearing. Second, the punishment inflicted bears no proportional relationship to the alleged act. A single accusation against one individual leads to the annihilation of the entire family’s economic foundation. Third, suspicion routinely substitutes for conviction. Properties are seized at the investigative stage rather than after a final verdict. Fourth, effective remedies are denied at the moment of greatest vulnerability. Legal appeals take months or years, while dispossession is immediate.

In legal terms, this transforms deprivation into punishment without trial. The deprivation is not regulatory. It is disciplinary. It is imposed not to manage land but to impose obedience. This directly violates the spirit and substance of the universal right to property (Human Rights Watch, 2021). India is a State Party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which legally binds it to uphold core civil liberties even in situations of internal disturbance. The ICCPR guarantees the right to an effective remedy, the right to a fair hearing and protection from arbitrary interference with one’s home and family (ICCPR, 1966). Property seizures in IIOJK rupture all three protections simultaneously.

There is no fair hearing before confiscation. Sealing orders are issued without summons, without evidence Patterns of Property Seizure and Confiscation25 testing and without adversarial process. There is no immediate effective remedy after confiscation because courts remain inaccessible to many victims due to fear, detention, geographic distance, or financial collapse. There is also direct state intrusion into the most intimate zone of civilian life: the home. The home becomes an object of security power rather than a sphere of personal liberty. The ICCPR does permit limited derogations during public emergencies but only under strict necessity and proportionality. What is unfolding in IIOJK does not meet these standards. The suspension of due process has become routine rather than exceptional. Emergency logic is being used to normalize permanent legal distortion. National security cannot function as a universal override through which all civilian safeguards are extinguished (Joseph & Castan, 2013).

Under international humanitarian law, the civilian population enjoys special protection against punitive state action. The Fourth Geneva Convention categorically prohibits collective punishment. It clearly states that no protected person may be punished for an offence he or she has not personally committed. It also prohibits collective penalties and measures of intimidation (ICRC, 2016). Property confiscation in IIOJK directly violates this prohibition. When the home of an entire family is seized for the alleged actions of one person, the state is imposing collective liability. When siblings and parents are rendered homeless for accusations they had no role in, the punishment becomes relational rather than individual. When neighborhoods are economically targeted through mass seizures to deter political sentiment, the punishment becomes communal.