INTERNATIONAL CONCERNS OVER KASHMIR ISSUE

INTERNATIONAL CONCERNS OVER KASHMIR ISSUE

INTRODUCTION

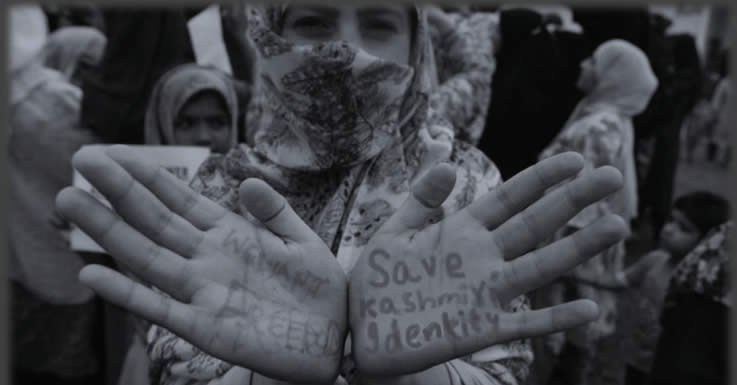

The following document presents a comprehensive compilation of international reactions to the issue of human rights violations in Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir, spanning the period from Sep 2023 to Dec 2023. This report aims to provide a consolidated overview of the statements made by prominent personalities and organizations and the extensive coverage provided by leading newspapers and magazines concerning the grave situation unfolding in this disputed region. The conflict in Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir has long been a matter of international concern, stemming from the aspirations of the Kashmiri people for self-determination. Throughout the years, numerous reports and testimonies have shed light on the violation of fundamental human rights and the immense suffering endured by the Kashmiri people. This report endeavors to bring together the voices of influential individuals and organizations that have expressed their concerns regarding the human rights situation in Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir.

It incorporates coverage of international media outlets including prominent newspapers and magazines, offering a comprehensive overview of the prevailing discourse surrounding the ongoing crisis. By compiling these international reactions and media coverage into a single document, we seek to underscore the urgent need for international attention and action in addressing the human rights abuses occurring in Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir. Through highlighting the perspectives of those who have spoken out against these violations, we aim to emphasize the pressing nature of the situation and advocate for the resolution of the Kashmir issue in a manner that upholds the rights and aspirations of the Kashmiri people. It is our sincere hope that this report will contribute to raising awareness about the challenges faced by the Kashmiri people and foster informed discussions among stakeholders and decision-makers.

By comprehending the gravity of the human rights situation, we can collectively work towards promoting peace, justice, and the realization of the legitimate right to self-determination for the people of Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir. We would like to encourage readers to thoroughly review the findings of this report, engage in constructive dialogue, and explore opportunities to support initiatives aimed at finding a just and lasting resolution to the Kashmir conflict. Together, we can strive for a future where human rights are upheld, and the aspirations of all communities in Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir are respected. Please note that this report represents a compilation of various sources and does not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of any specific individual or organization?”

JOINT OPEN LETTER: CALL FOR AN END TO HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN KASHMIR AND RELEASE OF JAILED HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS AND POLITICAL PRISONERS

ATTN: Representative of G20 member countries, guest countries, and invited international organizations We, the undersigned organizations, would like to bring to your attention serious concerns regarding human rights violations occurring in Indian-administered Kashmir (IAK) including the unlawful detention and persecution of human rights defenders and journalists. As your leaders prepare to attend the G20 Summit in September 2023, we urge your government to raise these issues directly and forthrightly with the government of India by your obligations under international law and call on India to adhere to its international legal obligations.

Four years after revoking important constitutional rights and protections for IAK, the Indian government has continued its repressive policies including restricting freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, and association, and failed to investigate and prosecute alleged violations committed by its military, paramilitary, police, and other forces. The authorities have also intensified their crackdown on independent media and civil society groups including through the frequent use of the abusive counterterrorism and state security laws, including the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) and Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act. These laws violate international norms and are systematically used by Indian authorities to incapacitate and persecute human rights defenders and dissenters in IAK.

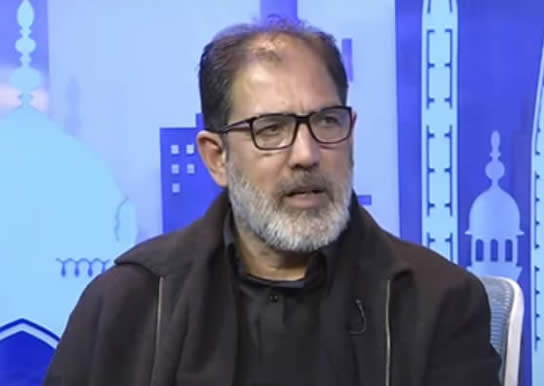

In November 2021, India’s National Investigation Agency (NIA) arbitrarily detained and illegally imprisoned prominent human rights defender Khurram Parvez, invoking powers under the UAPA as a reprisal for his human rights work in IAK. Khurram is the Program Coordinator of the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS), and the Chairperson of the Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances (AFAD). He is also the Deputy Secretary General of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and in February 2023, he was awarded the prestigious Martin Ennals Award, an annual prize that recognizes human rights defenders.

In addition to its persecution targeting Khurram, the NIA is also targeting JKCCS and anyone associated with the organization. In March 2023, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, Mary Lawlor, expressed her concern over the targeting of JKCCS and stated that the organization “carries out essential work monitoring human rights.” On 20 March 2023, the NIA arrested journalist and human rights defender Irfan Mehraj in connection with the JKCCS case. The NIA has publicly stated that one of the grounds for Irfan’s arrest was his close association with Khurram Parvez and JKCCS who were ‘funding terror activities in the valley and propagating secessionist agenda in the Valley under the garb of protection of human rights.’

Both human rights defenders remain illegally imprisoned in the maximum-security Rohini Jail in New Delhi. Journalists in Kashmir also face extreme levels of harassment by security forces, including interrogation, raids, threats, physical assault, restrictions on freedom of movement, and prosecutions under counterterror laws for their reporting. Among those in detention include Fahad Shah under the UAPA and Sajjad Gul under the PSA. In June 2020, the government announced a new media policy that made it easier for the authorities to censor news in IAK. For years, Indian authorities have routinely restricted and blocked the internet in IAK and prohibited international journalists, human rights defenders, and impartial observers from entering IAK, preventing critical reporting of human rights violations in the region. IAK experienced more internet shutdowns and restrictions than any other region in the world again in 2022, with over 49 internet suspensions.

Further, the usage of travel bans and passport revocations - without providing any explanation - poses an additional barrier to human rights defenders and journalists. Worryingly, in May 2023, the G20 held a tourism meeting in IAK which the UN Special Rapporteur on Minority Issues, Fernand de Varennes, said was being used to “normalize what some have described as a military occupation by instrumentalizing a meeting”. He noted that “the G20 is unwittingly providing a veneer of support to a facade of normalcy at a time when massive human rights violations, illegal and arbitrary arrests, political persecutions, restrictions, and even suppression of free media and human rights defenders continue to escalate.”

The Indian government as a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) has an obligation to respect and protect fundamental freedoms and ensure a safe and enabling environment for civil society. Further, in 2019, the importance of protecting “civic space” was recognized as a term by the Civil 20 - one of the eight official Engagement Groups of the G20 - held in Japan in both the final report and Tokyo Declaration. According to both documents, protecting civic space is necessary to tackle global challenges. It should be noted that civic space was also present in the C20 in the 2020 and 2021 communique and report In addition, the G20 Civic Space Sub-Working Group published a policy brief in July 2022 calling G20 leaders to act to protect and expand civic space. The policy brief points out how civic space is challenged globally by restrictive policies that limit the freedom of association, assembly, expression, and other civil and political rights.

The sub-working group concluded that “due to inadequate legal protection that most countries are having, human rights defenders are now at a greater risk of getting hostile retaliation from state and non-state actors when exercising rights to defend public interest.” Therefore, we urge your government to call on the government of India to:

• Immediately and unconditionally release Khurram Parvez and Irfan Mehraj, drop all charges against them and to end the ongoing persecution and targeting of Kashmiri human rights defenders, journalists, dissenters and political prisoners;

• Comply with their international legal obligations and allow civil society to freely operate in IAK;

• Cease their longstanding obstruction of international civil society and intergovernmental organisations including the United Nations Special Rapporteurs and other human rights mechanisms which should have unfettered access to IAK and Kashmiri detainees.

Signed by:

Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances (AFAD)

Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA)

CIVICUS: World Alliance for Citizen Participation

Front Line Defenders

Kashmir Law & Justice Project (KLJP)

INDIA:TWO YEARS OF ARBITRARY DETENTION OF KASHMIRI HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDER KHURRAM PARVEZ

We, the undersigned organisations, call for the immediate and unconditional release of human rights defenders Khurram Parvez and Irfan Mehraj, who are currently being detained in Rohini jail in India. Khurram has been in pre- trial detention for two years now, on politically motivated charges under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), an Indian counter-terror law that violates international human rights standards. Irfan has been in pre-trial detention since March 2023, similarly on politically motivated charges. Indian authorities’ persecution of Khurram and Irfan is an emblematic part of their ongoing, systematic criminalization of civil society, and the defense of human rights, in Indian-administered Kashmir.

Khurram is the Coordinator of Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS) and presently the Deputy Secretary- General of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH). He has, for years, documented human rights violations in Indian-administered Kashmir, including enforced disappearances and unlawful killings. He was awarded the 2022 Martin Ennals Award for his tireless human rights work. His outstanding human rights work has been met with Indian authorities’ unrelenting repression. Khurram was arrested on 22 November 2021 by the National Investigation Agency (NIA), India’s counter-terrorism agency, on various trumped-up charges including “waging, or attempting to wage war, or abetting waging of war, against the Government of India,” “punishment for conspiracy to wage war against the Government of India,” “raising funds for terror activities,” “punishment for conspiracy,” and other provisions of the UAPA and the Indian Penal Code. He was arrested after raids and seizures conducted at his office and home by the NIA on 21 November 2021.

In March 2023, Khurram was arrested again in another case registered in 2020 by the Indian authorities on fabricated charges of “terror financing” along with independent journalist Irfan Mehraj, who was formerly associated with JKCCS. The NIA filed a charge-sheet against Khurram and Irfan in this case on 15 September 2023. Khurram had previously faced targeted reprisals from the Indian authorities for defending human rights in Kashmir. In September 2016, he was prevented from travelling to Switzerland to attend the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council and later was arrested under the Jammu& Kashmir Public Safety Act and arbitrarily detained in prison for 76 days. The UAPA, has been increasingly abused by Indian authorities to bring politically motivated charges against human rights defenders. UN experts in May 2020 expressed their concerns about various provisions of the UAPA and its non-conformity with international human rights laws and standards.

The experts noted that provisions in the UAPA such as the powers to detain a person for up to 180 days “without providing any evidence” were particularly problematic and highlighted Section 43 D (5) of the UAPA, which makes it “highly unlikely” for a person arrested under this law to be released on bail.On 31 October 2023, UN experts again raised concerns about the UAPA, stating that the pre-trial detention period of 180 days, which can subsequently be increased, is beyond reasonable and called for a review of the UAPA in line with international human rights standards and with recommendations made by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) in its opinion published in June 2023, said that Khurram’s detention was “arbitrary” and called on the Indian authorities to immediately release him.

The reprisals and judicial harassment against Khurram are occurring within a larger context of systematic, longstanding, grave human rights violations by Indian authorities in Indian-administered Kashmir and impunity for those violations. Since the abrogation of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution in August 2019, Indian authorities have forcibly closed the already highly restricted civic space in the region. Journalists continue to face targeted harassment including arrests, travel bans, and passport suspensions for their reporting. Access to information is severely restricted through arbitrary internet shutdowns. Our organisations call on the Indian authorities to immediately and unconditionally release Khurram Parvez and Irfan Mehraj, to drop all charges against them, and to end all kind of harassment against all Kashmiri human rights defenders and civil society organisations.

India must also amend the UAPA to bring it in conformity with international human rights laws and standards, end the criminalisation of human rights defenders and journalists; and ensure accountability for human rights violations committed by Indian forces in Indian-administered Kashmir. We also call upon the Indian authorities to immediately comply with their international legal obligations, by allowing civil society to freely operate in Indian-administered Kashmir and India, and by ceasing their longstanding obstruction of international civil society and inter-governmental organisations, including the UN Special Rapporteurs and other human rights mechanisms which should have unfettered access to Indian-administered Kashmir and Kashmiri detainees.

Signatories:

• ALTSEAN-Burma

• Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network (ADPAN)

• Armanshahr Foundation / OPEN ASIA, Afghanistan

• Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances (AFAD)

• Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA)

• Association marocaine des droits humains (AMDH), Morocco

• Awaz Foundation Pakistan: Centre for Development Services (AWAZCDS), Pakistan

• Banglar Manabadhikar Surakshya Mancha(MASUM), India

• Bytes for All, Pakistan

• Capital Punishment Justice Project (CPJP)

• Center for Prisoners’ Rights, Japan

• Centro de Políticas Públicas y Derechos Humanos (Perú EQUIDAD), Peru

• CIVICUS: World Alliance for Citizen Participation

• Civil Society And Human Rights Network, Afghanistan

• Comisión Mexicana de Defensa y Promoción de los Derechos Humanos, Mexico

• Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ),

Northern Ireland

• Dakila - Philippine Collective for Modern Heroism, Philippines

• Defence of Human Rights, Pakistan

• FIDH (International Federation for Human Rights), within the framework of the Observatory for the

• Protection of Human Rights Defenders

• Front Line Defenders (FLD)

• Globe International Center, Mongolia

• Human Rights Alert, India

• Human Rights Association (Insan Haklari Dernegi IHD), Turkiye

• Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), Pakistan

• Human Rights Defenders Alert (HRDA), India

• Human Rights Online Philippines (HRonlinePH), Philippines

• Informal Sector Service Center (INSEC), Nepal

• IMPARSIAL (The Indonesian Human Rights Monitor), Indonesia

• Justiça Global, Brazil

• Karapatan, Philippines

• Kashmir Law and Justice Project

• Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law (KIBHR), Kazakhstan

• KontraS, Indonesia

• League for Defence of Human Rights in Iran (LDDHI), Iran

• Ligue des droits de l’Homme (LDH), France

• Madaripur Legal Aid Association (MLAA), Bangladesh

• Maldivian Democracy Network (MDN), Maldives

• National Commission for Justice and Peace (NCJP),

Pakistan

• Odhikar, Bangladesh

• Organisation National pour les droit de l’Homme, Senegal

• People’s Watch, India

• Pusat KOMAS, Malaysia

• Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit (RMMRU), Bangladesh

• Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM), Malaysia

• Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM)

• Task Force Detainees of the Philippines (TFDP), Philippines

• The Awakening, Pakistan

• Think Centre, Singapore

• Tunisian Association of Women Democrats (ATFD), Tunisia

• Vietnam Committee on Human Rights (VCHR), Vietnam

• World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

• YLBHI (Indonesia Legal Aid Foundation), Indonesia

HOW INTERNET SHUTDOWNS WREAK HAVOC IN INDIA

or nearly three months, the Indian state of Manipur had been raked with bloody violence between the majority Hindu Meitei and predominantly Christian Kuki-Zo tribes. But when a shocking 26-second video—which showed armed Meitei men stripping two Kuki women and parading them naked through the streets of Kangpokpi district—went viral in mid-July, the crisis sparked international condemnation and finally broke the Indian government’s silence. The criticism grew after police records showed the incident occurred on May 4, raising questions over why the video only surfaced 78 days later.

The answer, experts tell TIME, is that the authorities shut off the internet in Manipur on May 3. The state government, led by the ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), says it did so to curb rumors and disinformation and quell the violence. But digital rights activists say there is no evidence that turning the internet off helped keep anyone safe—and that the move may have even fueled violence. “The Manipur shutdown crippled the ability for information to reach the rest of the world,” says Mishi Choudhary, an Indian technology lawyer based in the U.S. who founded the Software Freedom Law Center, or SFLC.in, to fight for digital rights back home. “If we had seen the videos hidden from us for almost 80 days back in May, we could have reacted to it sooner.”

While the internet shutdown in Manipur may be one of India’s longest shutdowns yet, it is hardly unprecedented. “By and far, India is the most brutal censor of the internet in the democratic world,” says Choudhary. Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, speaks to members of the media ahead of the monsoon session of Parliament in New Delhi on July 20. A video of two women being paraded naked by a group of men in Manipur has elicited first public comments from Modi regarding the ethnic violence that has engulfed the relatively remote Indian state. Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, speaks to members of the media ahead of the monsoon session of Parliament in New Delhi on July 20.

A video of two women being paraded naked by a group of men in Manipur has elicited first public comments from Modi regarding the ethnic violence that has engulfed the relatively remote Indian state.Prakash Singh—Bloomberg/Getty Images A notification message is displayed on a smartphone regarding internet service being suspended as per the government instructions in Kolkata, on Dec. 17, 2019. According to officials, the government has shut down Internet services in several districts to prevent circulation of fake news on the nationwide protest against NRC, CAB. A notification message is displayed on a smartphone regarding internet service being suspended as per the government instructions in Kolkata, on Dec. 17, 2019. According to officials, the government has shut down Internet services in several districts to prevent circulation of fake news on the nationwide protest against NRC, Images India has ranked first in the world for shutting off the internet over the past five years, according to SFLC.in and other digital rights watchdogs.

In the first six months of this year, it imposed almost as many shutdowns as it did in all of 2022, according to Surfshark, a Netherlands- based virtual private network (VPN) provider. In addition to cutting off the internet, the government also routinely blocks specific websites or successfully pushes social media platforms to block content in India. Last year, that included nearly 7,000 posts and social media accounts, according to the nonprofit Access Now. In Manipur, the government’s first course of action after the viral video triggered global outrage was to ask Twitter and other social media platforms to take it down because it could “further disrupt the law and order situation in the state,” a senior government official told The Indian Express on July 21. Four days later, Manipur’s high court intervened to direct the government to restore the internet, but in a “limited fashion.” This means that social media websites, WiFi hotspots, VPNs, and mobile internet—used by the vast majority of Manipur’s 2.2 million people—remain blocked. The Internet Freedom Foundation in New Delhi has called this “illegal” and a deprivation “of basic human rights.” As Manipur entered its 100th day of an internet shutdown on Friday, a far broader debate has emerged across India about the use of shutdowns, whether they work, and what social and economic costs they bring on.

The current era of total internet shutdowns began in India on Aug. 5, 2019, when the Muslim-majority region of Kashmir entered what would eventually be the world’s longest internet shutdown—lasting 552 days—which the Indian government imposed after controversially revoking the state’s constitutional autonomy. Authorities eventually reinstated 4G mobile services in 2020, after the Supreme Court determined the ban could not be indefinite. Although internet access had been restricted around the country before, Kashmir was a “complete communications blockade,” says Choudhary. Kashmiri journalists hold placards and protest against 100 days of internet blockade in the region in Srinagar, Indian controlled Kashmir, on Nov. 12, 2019. Internet services have been cut since Aug. 5 when Indian- controlled Kashmir’s semi-autonomous status was removed. Kashmiri journalists hold placards and protest against100 days of internet blockade in the region in Srinagar, Indian controlled Kashmir, on Nov. 12, 2019. Internet services have been cut since Aug. 5 when Indian-controlled Kashmir’s semi-autonomous status was removed. Mukhtar Khan—AP

Since then, the Indian government has imposed total shutdowns in many cases of communal unrest or public protests occurring across the country. To date, India has experienced a whopping 752 shutdowns since 2012, SFLC.in estimates. The Indian government has not released a detailed accounting of the use of shutdowns. In July, Minister of Electronics and Information Technology Rajeev Chandrasekhar said the government does not maintain “centralized data” on the number of shutdowns imposed in India, and added that there was “no report available” to assess the economic loss. (Chandrasekhar was not available for comment.) India had no laws to regulate Internet shutdowns until 2017, when the Indian Telegraph Act of 1885 was amended to say that shutdowns could only be ordered by a state government’s home secretary when deemed “necessary” or “unavoidable” in public emergencies or in the interest of public safety.

The amendments also dictate that a district magistrate, the administrative officer in charge in every state, must regulate shutdowns by clearly stating the rationale behind the decision in writing, which is then reviewed by a bureaucratic committee within three days. But there is considerable latitude because terms like “public safety” and “public emergency” are not defined. In 2021, the internet was switched off when Indian farmers staged a months-long protest against new farm laws in the nation’s capital; in 2022, it was switched off in the city of Udaipur, in western India, when a Hindu tailor was murdered by a Muslim man in an incident that prompted fears over communal violence; and earlier this year, it was switched off once more when Punjab was placed under a three-day cellular blackout as police went on a manhunt to track down Amritpal Singh, a separatist Sikh leader on the run.

Sometimes the government implements shutdowns for seemingly mundane reasons—like preventing cheating in school exams or entry tests for competitive government jobs. A report by the Internet Freedom Foundation and Human Rights Watch found that almost a third of the disruptions counted from 2020 to 2022 were intended to prevent exam cheating. The Supreme Court sought to toughen the rules against imposing shutdowns when it heard the case “Anuradha Bhasin versus the Union of India” regarding Kashmir. In a landmark verdict, the court prohibited the government from suspending the internet indefinitely and limited shutdowns to 15 days or less, providing a detailed set of guidelines to regulate such orders. But the new guidelines did not prevent the shutdown in Manipur, which continues to be enforced through orders re-posted every few days. To SFLC.in’s Choudhary, the implications of this are clear.

“Whether it’s 78 days in Manipur or 552 days in Kashmir, internet shutdowns constitute a digital war in today’s India,” she says. Houses are seen burnt following ethnic clashes and rioting in Sugnu, in the northeastern Indian state of Manipur, on June 21. Houses are seen burnt following ethnic clashes and rioting in Sugnu, in the northeastern Indian state of Manipur, on June 21. Altaf Qadri—AP The impact of internet shutdowns is only growing as more and more people rely on an internet connection for their social and economic livelihoods. In large part, that’s because India’s Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, has for years pushed for a “Digital India” to transform the country’s economy and boost growth. India has built an extensive, public-facing digital infrastructure over time that includes a biometric identity system, a digital payment interface that allows payment through QR codes (and which now accounts for over 70% of all non-cash retail payments in India), and an online data management system containing IDs, tax documents, vaccine certificates, and more.

“On the one hand, the government pushes us all to live online, and on the other, it maintains a kill switch and uses it often,” Choudhary says. “And once you use that, you bring the entire economy and the entire social services to its knees.” Top10VPN, a global digital privacy and research organization, estimates the overall cost of shutdowns in India was $184.3 million in 2022. The figure is likely an underestimate; it excludes the informal work sector and not every shutdown is reported. The cost estimate also masks the ways in which shutdowns affect specific communities, typically poor or marginalized ones. In Kashmir, for example, at least 500,000 people—mostly in the tourism sector—became unemployed as a result of the shutdown in 2019, according to a report by the Kashmir Chambers of Commerce and Industry.

And many experts say the shutdowns don’t work, even judging by the rationale the government uses for them. “What helps people keep safe in any crisis is the ability to access and exchange information,” says Namrata Maheshwari, who serves as Access Now’s Asia Pacific legal counsel, “and shutdowns can never be justified because they’re always inherently a disproportionate measure.” They say that India’s situation is especially concerning given that in 2013 it joined many countries to proclaim, under Article 19 of the U.N.’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, that the right to freedom of expression and information “must also be protected online.” “There could not be a clearer basis for the illegitimacy of Internet shutdowns,” wrote Tanja Hollstein and Ben-Graham Jones, in an op-ed for the Westminster Foundation for Democracy. Yet Indian authorities continue to double down on their approach. After the sexual assault video in Manipur garnered international headlines last month, the state’s chief minister, N. Biren Singh, said that “hundreds of similar cases have happened, that is why the internet is banned.” For digital rights activists, not to mention the people in Manipur left in the darkness, such comments are dismaying. “When they say there are hundreds of crimes like the one we’ve already seen, then what is the point of all the shutdowns?” asks Choudhary.

‘ANY STORY COULD BE YOUR LAST’ INDIA’S CRACKDOWN ON KASHMIR PRESS

SRNAGAR — On 5 April 2022 a sense of joy pervaded the Sultan household in Batamaloo in central Srinagar. It was a sunny spring day in Indian-administered Kashmir, and after more than three and a half years of visits to courts and police stations, they had received good news — Asif Sultan, a journalist, husband, father and son, had been granted bail. Relatives gathered waiting for him to return home. When hours turned to days, Asif’s family began to get anxious. On 10 April, another charge was brought against Asif. He wasn’t released and was moved to a jail outside Kashmir, making visits difficult. “We are devastated but will keep fighting in court. Everyone knows he’s innocent so we will win eventually,” his father Mohammad Sultan said. His five-year-old granddaughter Areeba ran into the room and sat on his lap — she was six months old when her father was arrested.

Asif Sultan was first charged with aiding militancy in Muslim-majority Kashmir, which has seen an armed insurgency against Indian rule since 1989. He is charged under an anti-terror law called the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) in which it’s extremely difficult to get bail. The second charge against him is under another controversial law — the Public Safety Act (PSA) — which allows detention without charge for up to two years. Mohammad Sultan rejects the accusations. He believes Asif was targeted for his work, in particular an article about an anti-India militant that Asif wrote a month before he was arrested in August 2018. “Asif is a professional reporter and he has been jailed for writing about the militancy. He has nothing to do with them [militants],” says his father. “They [the government] wanted to make an example out of him so that no one dares to cover topics the government doesn’t approve of.”

The BBC has spent more than a year investigating accusations against the Indian government that it is running a sinister and systematic campaign to intimidate and silence the press in the region. We had to meet journalists in secret, and they asked for their names to be hidden, fearing reprisals. Over many trips we spoke to more than two dozen journalists — editors, reporters and photojournalists working independently as well as for regional and national outlets — all of whom see the government’s actions as a warning to them. Asif has now spent five years in jail. Since 2017, at least seven other Kashmiri journalists have been jailed. Four, including Asif, are still behind bars.

Fahad Shah, who edited a digital magazine, was arrested under anti-terror laws in February 2022, accused of “propagating terror”. A month before him, freelance journalist Sajad Gul was arrested soon after he posted a video on social media of locals shouting anti-India slogans. Sajad was charged with criminal conspiracy. Both have been re-arrested under new charges, each time they have been granted bail. The latest journalist arrest was in March this year. Irfan Meraj, whose work has appeared in international outlets, is accused of having links with terror funding. Many others from the press have had cases registered against them. The BBC has repeatedly asked the regional administration and police to respond to the allegations against them. We have sought interviews and also sent emails with specific questions. We have not received a reply.

At the G20 meeting in Srinagar in May we asked Manoj Sinha, the region’s top administrator, about allegations of a media crackdown. He said the press “enjoys absolute freedom”. Journalists were “detained and arrested on terror charges and for attempts to disrupt social harmony, not for journalism or for writing stories,” he said. We have heard multiple accounts which belie the claims. “It’s very common for a journalist to be summoned by the police here. And dozens of instances where reporters have been detained over their news reports,” one reporter told me. “I started getting calls from the police about a story I did. They kept asking why I’d done it. Then I was questioned in person. They said they know everything about me and my family which was very scary. I kept thinking about whether I would be arrested or harmed physically.”

More than 90% of the journalists I spoke to said they had been summoned by the police at least once, many of them multiple times over a story. Some said the tone of the police was polite. Others said they were met with anger and threats. “We live in fear that any story could be our last story. And then you’d be in jail,” one journalist said. “Journalism is dead and buried in Kashmir,” another reporter told me. Each of the journalists I spoke to said they had been called by the police numerous times over the past few years for “routine background checks”. I was witness to one such phone call. The journalist I was with got a call from the local police station. They put their phone on speaker. The police officer introduced himself and asked the journalist their name, address and where they worked. When the journalist asked why these details were needed, the officer’s tone remained friendly but he proceeded to read out details of the journalist and their family, including what their parents do, where they live, where their siblings study and work, what degrees their siblings have and the name of the business that one of their siblings runs.

I asked the journalists how they felt after that call. ‘It’s worrying,” they said. “I’m thinking now are they watching me, are they watching my family, what triggered this phone call and what’s going to happen next?” Other journalists said they have been asked even more personal details including what property theyown, what bank accounts they have, what their religious and political beliefs are. “Journalists in Kashmir are being treated like criminals. We’re labeled as anti-nationals, terror sympathizers, and pro-Pakistan reporters. They don’t understand that it’s our job to reflect all sides,” one journalist said. All of the Kashmir region is disputed by India and Pakistan, and both countries as well as China control parts of it. Militant groups operating in Indian-administered Kashmir are based in Pakistan and are long believed to have the support of Pakistan’s intelligence services, an allegation Islamabad firmly rejects.

There have also long been accusations of human rights violations by Indian security forces in Kashmir, which have fuelled anger against Indian rule and support for pro-Pakistan insurgent groups in some parts of the region. Journalists say the Indian government is trying to shut down reporting related to separatist movements and militant groups, but also any coverage critical of the security forces or the administration, even on day-to-day civic issues. Most journalists I spoke to said they began to feel more scrutiny after Asif Sultan’s arrest in 2018, and things have become drastically more difficult since August 2019. That’s when India revoked the region’s special status and divided the country’s only Muslim majority state into two territories which are now controlled by the national government led by the Hindu nationalist

Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The Supreme Court of India is currently hearing a case about the legality of these moves. For five years now, there has been no elected regional government here. And when the chief justice asked the government this week when elections would be held, noting that “restoration of democracy is important”, the government said it could not give an exact timeline. “Because there’s no elected representative we can approach, the government gets away with acting with impunity,” a journalist said. At least four Kashmiri journalists have made public that they were stopped from flying out of India, their boarding passes stamped “cancelled” by immigration authorities with no reasons given. One is a Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer who couldn’t attend the awards ceremony.

The BBC has learnt that the list of Kashmiri journalists not allowed to leave India has dozens of names, but it’s not been made public. We asked the police about the legal basis for these “look out circulars”, as they are referred to in official parlance, and have not received a reply. Journalists have also had fresh passports withheld when they applied to renew expired passports. In recent weeks, passports previously issued to some journalists have also been cancelled. Communication from the government says the journalists are considered a “security threat”to India. “We feel choked and suffocated,” one journalist said. “All of us are self-censoring. I read my report once as a journalist, then I read it like a policeman would and I start deleting things and watering it down. There’s hardly any journalism being done, it’s mostly just PR for the government.”

Editors have told us they often get directions from the administration on what to cover and what to leave out. They have been instructed to use the word “terrorist” instead of “militant” when referring to armed insurgents. Regional media outlets depend heavily on government advertising and many have been threatened with the withdrawal of these funds if they don’t fall in line. “I hate what I do every day, but what about the people I employ? What happens to them if I shut down?” one editor said. What’s happened to journalism here is evident when you read the local press. I spent three days comparing dozens of papers published in Kashmir with the daily government press release. Nearly all had the release on their front pages, some had edited it, others carried it verbatim. The rest of the front pages were covered with statementsMfrom the government or security forces. There were many feature stories but barely any journalism holding the government to account.

In June, allegations surfaced of Indian army personnel entering a mosque in Pulwama in southern Kashmir and shouting “Jai Shri Ram” (Hail Lord Ram), a Hindu chant. In normal circumstances, journalists from all outlets would have been in Pulwama speaking to all sides on the ground to verify details and filing reports. The day after, only a handful of papers carried the story, nearly all reporting it through a quote from regional politician Mehbooba Mufti, who called for an investigation. Over the next few days, more papers carried it, but only as a story about the Indian army investigating the incident. There was barely any on-the-ground reporting. While most journalists I spoke to said they fear reprisals by the state, some also said they feel under threat from militants.

There have been instances of militant groups posting statements on their websites threatening journalists. I spoke to one journalist who received a threat. “A journalist’s life in Kashmir is like walking on a razor’s edge. You live in fear all the time,” he said What are you afraid of, I asked. “Of a bullet coming at me. When I see a motorcycle stop next to me, I feel terrified that someone is going to pull out a gun and shoot me, and that no one will ever find out who did it,” he said. In 2018, leading editor Shujaat Bukhari was shot dead outside his Srinagar office, police say by militants. Five years later the trial into his killing is yet to begin. In a region ridden by conflict, one space where journalists could meet freely, discuss stories and share their anxieties was the Kashmir Press Club in central Srinagar.

It was a refuge especially for independent journalists who don’t have offices. But it wasn’t just that. It was also the main body in the region that defended the rights and freedom of the press. Last year, the government shut it down. The complex I’ve visited so often to get invaluable local insight into stories, now houses a police office. Journalists say they have nowhere to turn to when they feel threatened. Foreign journalists need Ministry of Home Affairs permission to visit Kashmir, and they are rarely given it. The G20 event in May was the first time in the past few years foreign journalists had been allowed to visit Srinagar, but the access was extremely controlled —defining which areas they could visit and what they could cover. Over the past decade, all of India has witnessed a serious decline in press freedom, which is reflected in global rankings, cases against journalists and raids against media houses. But the degree of the decline in Kashmir is extreme — we have found evidence that press freedom has been all but eroded here.

In the Sultan household, a copy of Kashmir Narrator, the magazine Asif Sultan used to write for, takes pride of place on a shelf in the living room. His father opened the well-thumbed magazine and pointed to Asif’s photo in a byline. Mohammad asked his granddaughter who the person in the picture was.“My Papa. He is in jail,” Areeba replied. Mohammad hopes Asif is released before Areeba gets to an age where she registers what has happened to her father. “I’m getting old,” he said. “But I’m trying to be both a father and grandfather to her. How long can I do this for?” — BBC

INDIA BLOCKS JOURNALISTS’ TWEETS ABOUT VIOLENCE AGAINST MUSLIMS

Since August 8, the X account of independent journalist Ahmed Khabeer has been blocked in India, he told CPJ by phone. Khabeer published the email he received from X, which said it had “received a legal removal demand from the Government of India regarding your Twitter account, @AhmedKhabeer_, that claims the following content violates India’s Information Technology Act, 2000.” The email did not provide any further details about the alleged illegal tweets. Khabeer told CPJ that he believed he was targeted for his extensive coverage of violence against Muslims and the Dalit minority that was “completely ignored by the mainstream media.” In early August, he posted videos which he said showed an attack on a Muslim man by the Hindu supremacist group Bajrang Dal and authorities’ demolition of Muslim homes in northern Haryana state.

Separately, independent journalist Rohini Singh posted two critical comments on X about a video of a teacher ordering her students to slap a seven-year-old Muslim student, which went viral after being published on August 25. Singh received two emails from X, reviewed by CPJ, which said her tweets had been withheld in India in response to demands from the Indian government under the IT Act. X also blocked tweets on the issue by other users of the platform. “I believe my tweets were withheld because the government has an issue with the reporting of a crime rather than the crime itself,” Singh told CPJ viamessaging app. Religious tensions are on the rise in India under the ruling right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which aims to transform secular India into a Hindu nation. NDTV news anchor Gargi Rawat also posted a link on X to her outlet’s article about the teacher slapping the student in northern Uttar Pradesh state. It was also blocked, she told CPJ via messaging app.

The three journalists told CPJ that they had not received any explanation from the government as to how they had violated the IT Act, which empowers the government to block content on vague grounds including the “sovereignty and integrity of India.” Digital rights experts say that India is not respecting its legal obligations under a 2015 Supreme Court order to provide a person or outlet that has allegedly produced offensive content with a copy of the blocking order and an opportunity to be heard by a government committee before it blocks their content. On August 12, X also suspended the account of NewsClick after a BJP lawmaker said in parliament that the independent website received funding from China to create an “anti-India” atmosphere. NewsClick is known for publishing articles critical of the BJP government. Its account was restored the following day. NewsClick’s editor-in-chief Prabir Purkayastha did not respond to CPJ’s messages requesting comment. The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology also did not respond to CPJ’s emailed request for comment.

INDIA: ARRESTS, RAIDS TARGET CRITICS OF GOVERNMENT

Counterterrorism Law Misused to Harass Journalists, Activists (New York) – Indian authorities are misusing an abusive counterterrorism law, financial regulations, and other laws to silence journalists, human rights defenders, activists, and critics of the government, 12 international human rights groups said today. On October 3, 2023, police in New Delhi arrested the editor and an employee of the news portal NewsClick, and raided the homes of 46 journalists seemingly connected to the digital news platform over allegations of illegal foreign funding, which the outlet has denied. Soon after the writer Arundhati Roy spoke out at a protest meeting that followed the raids, authorities said they would prosecute her and a Kashmiri academic for allegedly “promoting enmity between different groups,” “causing disharmony,” and “public mischief,” for a speech she had made 13 years ago, in 2010. A case was also registered under the counterterrorism law, Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), against them.

The groups are Amnesty International, Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUMASIA), Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW), Committee to Protect Journalists, Front Line Defenders, Human Rights Watch, International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), International Service for Human Rights, PEN America, Reporters Without Borders, International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), and World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) in the framework of the Observatory. The arrest and raids at NewsClick, an outlet known to criticize the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led government for failing to uphold human rights, are the latest attempts by authorities to harass and intimidate independent journalists, the groups said. The authorities sealed NewsClick’s Delhi office and seized several journalists’ electronic devices, including laptops and phones without ensuring the integrity of their data, essential to ensuring due process.

Since the BJP government, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, came to power in 2014, Indian authorities have carried out an escalating crackdown on the media and civil society. They have arrested journalists on spurious terrorism and other criminal charges, and have routinely targeted critics and independent news organizations with allegations of financial irregularities. Similarly, they have used the counterterrorism law, national security laws, foreign funding laws, and income tax regulations to target and prosecute human rights defenders and peaceful protesters. Journalists and activists from minority groups are particularly at risk, the groups said. During the latest raids, the authorities also searched the Mumbai home of a prominent human rights activist, Teesta Setalvad, in apparent retaliation for writing NewsClick articles criticizing the government. The government has repeatedly targeted Setalvad and jailed her on politically motivated charges of criminal conspiracy and forgery while she was pursuing accountability for the 2002 anti-Muslim violence in Gujarat state.

Regardless of the veracity of the allegations of foreign funding, raiding a media outlet and arresting its journalists on terrorism charges is a grossly disproportionate measure, the groups said. In September 2021, tax and financial regulators raided journalists’ homes and offices of news websites Newslaundry and NewsClick, an actor’s premises, and the home and office of the human rights activist Harsh Mander. In February 2023, Indian tax officials raided the BBC offices in New Delhi and Mumbai in an apparent reprisal for a two-part documentary that highlighted Modi’s record in failing to protect Muslims. The government blocked the BBC documentary in India in January, using emergency powers under the Information Technology Rules.

The government is increasingly using the counterterrorism law, Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), to target its critics. The law defines terrorism in a vague and overbroad manner, reverses the presumption of innocence, allows for prolonged detention without trial or charge for up to 180 days, including up to 30 days in police custody, and creates a strong presumption against bail. In November 2021, the authorities arrested a prominent Kashmiri human rights activist, Khurram Parvez, under the UAPA. On March 22, 2023, the authorities added another case of financing terrorism under UAPAagainst Parvez, while Irfan Mehraj, a journalist formerly associated with Parvez’s human rights organization, was arrested in the same case.

The Kashmir Walla editor Fahad Shah and a reporter, Sajad Gul, have been detained since early 2022. After being granted bail in separate cases, both were rearrested – without being released – under the Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act (PSA), a draconian preventive detention law that allows for up to two years in custody without trial. While the Jammu and Kashmir High Court quashed the PSA order against Shah, he remains jailed while facing trial in a separate UAPA case in relation to a 2011 article on his website, whose author, contributor Abdul Aala Fazili, has been detained since April 2022. Similarly,another Kashmiri journalist, Aasif Sultan, detained since August 2018, was granted bail in a UAPA case in April 2022, but rearrested under the PSA five days later. The Indian government also used UAPA to arrest 16 prominent activists who promoted the rights of India’s most marginalized communities, accusing them of inciting violence that occurred during a Dalit meeting in January 2018. Eight are still detained without trial, and seven eventually were granted bail, while one died in custody.

According to reports by the US-based forensic firm Arsenal Consulting, malware was used to surveil and plant evidence on the computers of two accused in this case, amplifying concerns surrounding the seizure of the NewsClick journalists’ devices without due process. The Delhi police filed politically motivated charges of sedition and terrorism against 18 activists, students, opposition politicians, and residents in relation to the communal violence in Delhi in February 2020. Several of those arrested were involved in organizing peaceful protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act. The Delhi High Court, while granting bail in June 2021 to three activists booked under UAPA, stated that “in its anxiety to suppress dissent, in the mind of the State, the line between the constitutionally guaranteed right to protest and terrorist activity seems to be getting somewhat blurred.”

An analysis of the latest crime data by Amnesty International found that despite the increased use of UAPA, there have been very few convictions. Only 2.2 percent of cases registered under the law from 2016 to 2019 ended in a court conviction. Nearly 11 percent of cases were closed by the police for lack of evidence, while the rest remained pending. The delay in filing charges and several acquittals in these cases show that the counterterrorism law is used to keep critics locked up for years, and send a chilling message to others who speak out, making the judicial process itself a tool for persecution and punishment. United Nations human rights experts have repeatedly condemned the use of UAPA to target journalists, human rights defenders, and other critics. The Indian authorities should immediately and unconditionally release all journalists, human rights defenders, activists, and critics arrested in politically motivated cases, drop all charges against them, and stop threatening, harassing, and intimidating them, including through criminal prosecutions, the groups said. The government should also amend the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act to bring it in line with international human rights standards and, pending its amendment, the government should stop using it to target critics.

INDIA: STOP ABUSING COUNTERTERRORISM REGULATIONS

Financial Action Task Force Review Should Document Crackdown on Dissent (London) – The global terrorism financing and money laundering watchdog, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), should call on the Indian government to stop prosecuting, intimidating, and harassing human rights defenders, activists, and nonprofit organizations in the country on the pretext of countering terrorist financing, Amnesty International, Charity & Security Network, and Human Rights Watch said today. FATF members are to start their fourth periodic review of India’s record on tackling illicit funding on November 6, 2023. Indian authorities have exploited FATF’s recommendations which aim to prevent terrorist financing as part of a coordinated campaign to restrict civic space and stifle the rights to freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly. Draconian laws introduced or adapted to this end include the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act (FCRA), the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), and the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA).

Their actions have flouted both FATF’s standards and international human rights law, the groups said. “The Indian authorities have weaponized laws to crack down on the human rights work by human rights defenders, activists, and non-profit organizations in the country,” said Aakar Patel, chair of board at Amnesty International India. “Authorities are using bogus foreign funding and terrorism charges to target, intimidate, harass, and silence critics, in clear violation of FATF standards.” The FATF, which India joined in 2010, is a 40-member country body mandated to tackle money laundering, terrorist financing, and other threats to the integrity of the global financial system. It advances its work through a set of recommendations, consisting of 40 international standards, to guide national authorities’ implementation of these goals through “legal, regulatory and operational measures.”

The task force standards, particularly Recommendation 8, require the scrutiny of only those nonprofit organizations that have been identified through a careful, targeted “risk-based” analysis on factors such as their vulnerability to being used as a front to finance terrorism related activities. In October 2023, the task force further revised its recommendations leaving “no room for implementation of measures that are not proportionate to the assessed terrorist financing risks and are therefore overly burdensome or restrictive for organisations working in the not-for-profit realm.” During its third FATF review, in 2010, the Indian government itself recognized the risk posed by the nonprofit sector as “low.” However, since the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power in 2014, the authorities have used overbroad provisions in domestic law to silence critics and shut down their operations, including by cancelling their foreign funding licenses

and prosecuting them using counterterrorism law and financial regulations. The Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, first enacted in 1976, was aimed at preventing and regulating foreign interference in Indian politics. However, in 2010, the government repurposed the legislation with a greater focus on nonprofit organizations, while relaxing foreign funding oversight for political parties. In the last 10 years, the authorities have used this law to cancel the licenses of over 20,600 nonprofit organizations, including 6,000 in 2022, blocking their access to foreign funding. In July 2022, the Home Affairs Ministry deleted the list of nonprofit organizations whose FCRA licenses had been cancelled without any explanation and stopped publishing this data. The Indian government has particularly targeted human rights groups and activists working to protect the rights of the most socially and economically marginalized populations. According to media reports, in 2023, the Home Affairs Ministry revoked the FCRA licenses of a leading research group, the Centre for Policy Research, and a social justice advocacy organization, the Centre for Equity Studies.

Indian authorities have also frequently used the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), India’s primary counterterrorism law, to arbitrarily arrest and detain human rights defenders and activists. The law was introduced as a reform to the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA) in 2004, but the government amended it in 2008, 2012, and 2019 to include many problematic provisions of POTA. They include its overbroad definition of a “terrorist act,” reversal of the presumption of innocence, and provisions for prolonged detention without trial or charge. To satisfy FATF’s membership conditions, India amended the UAPA in 2012 to include threats to economic security and also extended the definition of a “person” liable to be charged under that law to international and intergovernmental organizations. India’s 2019 amendment extended the law’s applicability from organizations and groups to individuals as well.

The counterterrorism funding provisions of the UAPA have been misused against several student activists who organized protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act. The government accused the students of “orchestrating” the February 2020 Delhi riots that killed at least 53 people, largely Muslims; and used the law against 16 human rights activists, eight of whom have remained detained without trial in the Bhima Koregaon case since 2018. The counterterrorism financing and other provisions have also been misused to detain Khurram Parvez, a prominent Kashmiri human rights activist who is program coordinator of the Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, and Irfan Mehraj, a journalist associated with the coalition. Despite the increased use of the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, only 2.2 percent of cases registered under the law from 2016 to 2019 ended in a court conviction.

The police closed nearly 11 percent of cases for lack of evidence, while the rest remained pending. The delay in filing charges and several acquittals in these cases show that the government is using the counterterrorism law to keep critics locked up for years and use the judicial process itself as a tool to persecute and punish government critics. The Indian government also enacted the 2002 Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) to satisfy membership conditions set by FATF. In recent years, authorities have used the law to attack intimidate, and harass human rights defenders, activists, and nonprofit organizations by supplementing the charges under FCRA, seizing their properties, and burdening them with stringent bail conditions. Amnesty International India has been subject to action under the PMLA through the freezing of its bank accounts in September 2020, putting its work on hold for the past three years, without funds to even secure effective legal representation.

“India’s three laws together have created a dangerous arsenal with debilitating consequences for civil society and human rights activists,” said Meenakshi Ganguly, Deputy Asia Director at Human Rights Watch. “The FATF should not allow the Indian government to exploit the organization’s recommendations for its political purposes– to silence all forms of dissent.” abusing-counterterrorism-regulations Nov 16, 2023 Indian American Muslim Council

JOURNALISTS INTERROGATED OVER ARTICLE ON ANTI-MUSLIM BIAS IN HANDLING OF KERALA BOMB CASE

Police in Kerala state summoned and interrogated Aslah Kayyalakkath, the editor of the independent news portal Maktoob Media, and freelance journalist Rejaz M. Sheeba Sydeek, over an article written by Sydeek that points out anti-Muslim bias in the police’s handling of a recent bombing case.The article reported that police had held young Muslim men in preventative detention “without proper leads” after a bomb attack targeting Jehovah’s Witnesses in Kerala. The men were detained both before and after a former Jehovah’s Witness claimed responsibility for the attack. A police report was filed against the article after its release, which Maktoob Media has slammed as “[threatening] the journalistic independence of reporting stories without reprisal.” Indian minister tells media to avoid platforming “anti- India views” amid shrinking press freedoms As Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government continues its crackdown on press freedoms, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leader and Information and Broadcasting Minister Anurag Thakur told members of the press to “avoid providing space to anti-India views” in the media.

“There are individuals and media outlets that consistently spread fake propaganda against Bharat, both domestically and internationally,” Thakur claimed at an event organized by the Press Council of India. “Anti-India” is a label often ascribed by the Hindu right to any criticism of Modi, the BJP, and Hindu supremacism. As such, mainstream Indian media has increasingly become a bullhorn for pro-Modi propaganda. BJP leader T. Raja Singh booked yet again for hate speech in election campaign Serial hatemonger and BJP leader T. Raja Singh, who has made consistently violent anti-Muslim hate speeches throughout the nation, has once again been booked for hate speech at an election rally. “See the fight we have between love Jihadis and Hindu daughters,” Singh claimed, invoking the anti-Muslim conspiracy theory of ‘love jihad,’ which falsely claims Muslim men have an agenda to convert Hindu women to Islam through seduction. “People all over the world know... that there is a servant of Hindus named Raja Singh, who will give a befitting reply to the Jihadis,” he added.

AFTER 658 DAYS IN JAIL, KASHMIR JOURNALIST FAHAD SHAH SHARES HIS STORY

On a chilly winter afternoon, Fahad Shah stares at the wilted flowers in the walled compound of his home on the outskirts of Srinagar. “It feels different to be free,” he says. “I wake up and see my family, and it feels good.” Mr. Shah, a prominent journalist from Kashmir and a contributor to The Christian Science Monitor, was released on bail last week after being jailed for 658 days. Indian authorities charged him with “glorifying terrorism” and publishing “anti-national content,” as well as receiving foreign funds illegally. The High Court of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, however, found insufficient evidence to try Mr. Shah on terrorism charges, and granted the beleaguered editor bail. The release of Fahad Shah is a triumph for the friends and family who’ve been fighting for the newspaper editor’s freedom. It’s also a rare moment of relief amid an ongoing crackdown on press freedom in the region.

Global media watchdogs and journalists from the region view Mr. Shah’s experience as part of a wider crackdown on media in Indian-controlled Kashmir, where authorities have been accused of intimidation, harassment, and the systematic targeting of critical voices. Press freedom advocates have welcomed Mr. Shah’s release, demanding that all remaining charges against him be dropped and the blockade on his popular news portal, The Kashmir Walla, be reversed. “Fahad’s ordeal reflects the challenges journalists in Jammu and Kashmir endure for doing their work,” says Kunal Majumder, India representative of the Committee To Protect Journalists (CPJ). “We also call for the immediate release of journalists Aasif Sultan and MajidHyderi, who face similar charges and are in preventive custody even after being granted bail by the court.”

“Authorities in Jammu and Kashmir must stop this trend of criminalizing journalists and be tolerant of critical and dissenting voices,” he adds. Kashmir’s ongoing media crackdown After his initial arrest in February 2022, Mr. Shah was held in a series of police facilities and jails across the region. After he secured bail in one case, authorities arrested him for another. When he secured bail in that too, they slapped him with the Public Safety Act, a draconian law that allows a person to be held in jail without trial, though the high court quashed that case months ago. He was eventually booked under four different cases in what rights groups describe as a “revolving-door detention.” Mr. Shah says this coordinated effort to keep him behind bars was crushing. “Every time I would feel like [I was] getting released, something new would happen,” he says. Last week, a court declared that local law enforcement lacked evidence to prove charges filed under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, a stringent anti-terror law, and that Mr. Shah did not pose a “clear and present” danger to society.

Keeping him in jail “would mean that any criticism of the central government can be described as a terrorist act because the honor of India is its incorporeal property,” states the court’s bail order. “Such a proposition would collide headlong with the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression enshrined in Article 19 of the constitution.” Indeed, these freedoms are under sharp threat in Kashmir. It has never been easy for journalists to operate in the heavily militarized Himalayan region, but under Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Kashmir – and India more broadly – has experienced a significant press freedom backslide. After the Modi government stripped the region of its limited autonomy and imposed a month slong communication blackout in 2019, the crackdown on Kashmiri journalists intensified. Many have been questioned by police, had their homes and news offices raided, been forced to reveal sources, and been barred from leaving the country. In August, authorities blocked access to The Kashmir Walla’s website and social media in India, effectively shutting down one of the region’s last independent media organizations without explanation.

Today, there are at least four Kashmiri journalists who remain incarcerated. Days after Mr. Shah’s bail, a court quashed the Public Safety Act charge against Sajad Gul, a Kashmir Walla trainee who has been in jail since January 2022. Mr. Gul has yet to be released. Another journalist, Irfan Mehraj, was arrested in March under terrorism charges, and Mr. Sultan and Mr. Hyderi, as mentioned by India’s CPJ representative, also remain imprisoned. Relatives, friends, and fellow journalists have been thronging Mr. Shah’s home since his release. “It is really moving to see so many of my colleagues,” says Mr. Shah. “Everyone was hugging, and there were these tight hugs, and people hugging twice, thrice; it made me feel I have not been forgotten. ... There are people who have been waiting to see me.” They discuss the state of journalism, fill him in on who got married while he was in jail, and crack jokes to lighten the mood. And when Mr. Shah describes his time in jail, legs covered under a blanket, everyone in the room listens intently.

“Prison breaks you bit by bit,” he says. He describes his “worst days” of incarceration during the initial months of his arrest, when he was confined to a small cell where he couldn’t stretch out his body properly. “I was not in touch with my family. I don’t know what was happening outside that cell,” says Mr. Shah, who looks frail and fatigued, with dried lips and dark circles under his eyes. “I was exhausted and mentally tortured. ... I used to get these hallucinations and imaginations about what must have happened at home.” Those who know him well say he looks shattered. But it wasn’t all so painful. After being sent to Kot Bhalwal jail in June 2022, Mr.Shah says he made peace with his new reality and tried to become part of the jail community.

“There are prisoners of different kinds and [from] different areas,” he says. “Only inmates are there for each other in happiness and gloom.” He also had time to read lots of books, mostly about his favorite subject: culture and media. “Other than that, I would read newspapers. But there wasn’t much to do,” he says. All the while, Mr. Shah says he felt like he was becoming a character in an article. The questions he so often asked as a reporter – about how long a person had been in prison, the charges against them, and what it was like being targeted by the state – were suddenly relevant to his own life. “There was a point when I was writing about these people, and then I became one of those people,” says Mr. Shah. “I became the character of my own story. Now it was about me.” journalist-Fahad-Shah-shares-his-story Dec 11, 2023 Amnesty International

INDIA: PROTECTION OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS OF THE PEOPLE OF JAMMU AND KASHMIR MUST GUIDE THE WAY FORWARD

Responding to Supreme Court’s verdict upholding the central government’s 2019 decision to abrogate Article 370 of the Indian Constitution which granted special status to the region of Jammu and Kashmir, Aakar Patel, chair of board at Amnesty International India, said: “For decades, the people of Jammu and Kashmir have faced grave abuse of their rights to physical and mental integrity, including arbitrary detention and unlawful killings, and to their freedoms of expression movement and from discrimination. The situation only exacerbated for them following abrogation of Article 370 in 2019. Today’s reported house arrest of regional political leaders ahead of the verdict is a stark reminder of the fear and uncertainty that persists in the region.

The people and their human rights need to be at the heart of the steps taken ahead in Jammu and Kashmir. Aakar Patel, chair of board at Amnesty International India “In this context, while the Supreme Court’s decision today can provide hope in restoring the inclusion of Kashmiri voices, any initiative must fully respect the human rights of people of J&K, including access to justice, truth and reparations. “In this regard, the call for setting up of an ‘impartial Truth and Reconciliation committee’ to investigate the human rights abuses in Jammu and Kashmir by state and non- state actors since the 1980s presents an opportunity to the Indian government to right the wrongs. The government needs to take up this call and demonstrate a strong political will to ensure there is a transparent and consultative process to set up an independent committee with a strong legal foundation, and funding and powers consistent with international law and standards. “The people and their human rights need to be at the heart of the steps taken ahead in Jammu and Kashmir.”

Background

On 11 December 2023, a Constitution Bench headed by the Chief Justice of India DY Chandra chud unanimously upheld the 2019 decision of the central government to abrogate Article 370 of the Indian Constitution. The revocation in 2019 was followed by the deprivation of Jammu & Kashmir’s statehood within India and splitting it into two separate union territories directly governed by the central government. Further, the Court today ordered the restoration of statehood of Jammu and Kashmir as soon as possible and proceeded to order the Election Commission of India to hold elections to the Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Assembly by 30 September 2024. In a concurring opinion, Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul recommended “the setting up of an impartial Truth and Reconciliation committee to investigate and report on the violations of human rights” both by state and non-state actors at least since the 1980s and “measures for reconciliation”.

Leaders of prominent political parties in Kashmir and former Jammu and Kashmir chief ministers Omar Abdullah and Mehbooba Mufti claimed they have been put under house arrest in the state. However, the Jammu and Kashmir Lieutenant Governor and police denied placing anybody under house arrest. Amnesty International has documented the continued repression of rights in Jammu & Kashmir since the change in status of the region in 2019 through the abrogation of Article 370 and has called for the Indian government to end the use of unlawful measures and unjust barriers impeding the exercise of various human rights in the region.

‘JAIL CRUSHES YOU SLOWLY’: KASHMIRI JOURNALIST REFLECTS ON PRISON ORDEAL

During his more than 600 days behind bars, Fahad Shah, a Kashmiri journalist, had begun to lose hope that he would ever see freedom again. It was in February last year that Shah, 34, the editor of the Kashmir Walla, one of the last remaining independent news websites in the region, was arrested on charges of “glorifying terrorism” and publishing “anti-national content”. What followed was a crushing 21 months for Shah as his high-profile case became a symbol of the growing harassment faced by Kashmiri journalists. He was granted bail in one case, only to be swiftly re-arrested and hit with new, more draconian charges. Even as the charges against him were gradually quashed and he was given bail in three of his four cases, it was not until last month that he was finally granted relief by the courts, who found insufficient evidence to charge him with terrorism. On 23 November, on the back of a fresh bail order, he walked free from Kashmir’s Kot Bhalwal jail.

How a terrorism law in India is being used to silence Modi’s critics Though filled with deep relief and happiness to be back with his family, Shah, speaking from his home in Srinagar, looked frail and drawn, huddled beneath a blanket. He spoke quietly about what he had endured and said he was not able to freely discuss the cases against him. “Jail crushes you slowly from inside,” he said. During his time behind bars, Shah was moved around to different jails and faced months of interrogation. “You get affected mentally and physically,” he said. “You reach a point where you are broken and you make peace with this new personality you become in the prison.” At one point he was kept for 20 days in solitary confinement in a 6ft-by-6ft cell, with no communication with the outside world. The harsh conditions made him ill and he began to hallucinate. “I did not know what was going on, that was a really worse period in this whole time,” he said.

Prior to his arrest, the Kashmir Walla had been one of the few news platforms in the region still publishing critical news and investigations about human rights abuses, amid an ongoing crackdown on independent media. Shah had also been an occasional contributor to the Guardian. After August 2019, when the ruling Bharatiya Janata (BJP) government in Delhi decided to strip Kashmir of statehood and bring it under direct government control, an internet and communications blackout was imposed for months and a systematic crushing of independent journalism began. Several journalists were jailed or have been charged in cases, some under draconian anti-terror laws, while others have endured police intimidation or days of interrogation and been forced to reveal their sources.

Many have been put on a blacklist and banned from travelling abroad. Strict regulations were passed to control the media and the once thriving press club was shuttered. Local newspaper adverts, their main source of revenue, were cut to bring the publications in line, barring them from reporting anything critical of the government. Kunal Majumder, the Committee to Protect Journalists’ India representative, said: “Fahad’s ordeal reflects the challenges journalists in Jammu and Kashmir endure for doing their work. Authorities in Jammu and Kashmir must stop this trend of criminalising journalists and be tolerant of critical and dissenting voices.” Days after Shah’s bail, a court quashed terrorist charges against another Kashmiri journalist, Sajad Gul, who has been in jail since January 2022. He is yet to be released, his family told the Guardian. There are three more Kashmiri journalists who remain incarcerated.

Despite struggling with resources, the Kashmir Walla had continued its work after Shah’s arrest, even when it could afford only six staffers, until authorities unilaterally blocked its website and shut down its office in August without warning. Though his publication has closed down, Shah vowed to continue working as a journalist in Kashmir, but he said his outlook on the world had changed. “I will be able to see things differently when I resume my work. I think the time spent in prison formed in me a new lens, through which I will be able to see things a little differently now.” Shah said he ultimately made peace with the reality of jail after being shifted to Kot Bhalwal, in the city of Jammu, in June last year, where he got access to books and newspapers and started interacting with inmates.

To his surprise, many prisoners knew him already, either because they had seen his work or he had interviewed them at some point as a reporter. Shah said he was still struggling to adjust to normal life at home. “In jail I had made plans about the things I would do after my release, the food I would eat, but allof those things have suddenly become unimportant,” he said. “My family is around and my colleagues have been visiting me, showing care and compassion. It feels like they have been waiting for this day.” kashmiri-journalist-fahad-shah-reflectson- prison-ordeal

INDIA’S SUPREME COURT UPHOLDS DECISION TO STRIP KASHMIR OF SPECIAL STATUS