HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT

HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT

INTRODUCTION

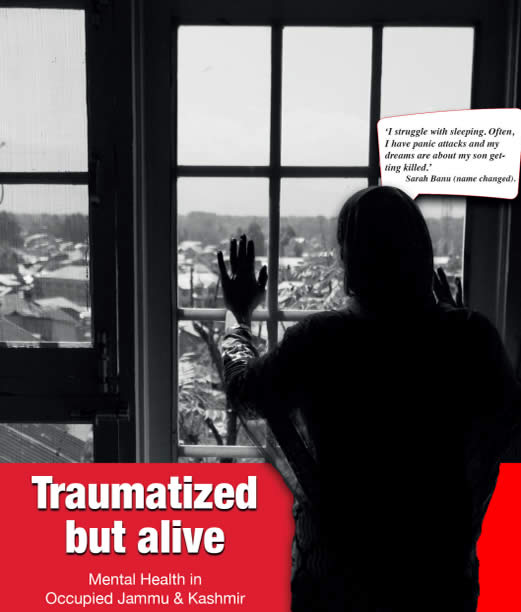

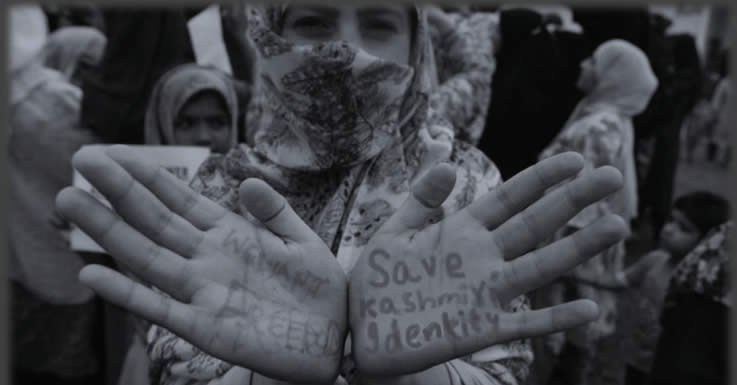

The period from September to December 2025 represents a critical phase in the continuing human rights crisis in Indian Illegally Occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IIOJK). These months did not mark a departure from earlier patterns of repression but rather exposed the cumulative consequences of policies imposed since 5 August 2019, when India unilaterally revoked the region’s special status. Despite repeated official claims of peace and normalcy, the lived reality across IIOJK remained defined by militarization, fear and the systematic denial of fundamental rights.

Since August 2019, the administration of IIOJK has been governed through extraordinary control measures rather than democratic engagement. Civilian life has been tightly regulated through checkpoints, surveillance, cordon-and-search operations and recurring curfews. Legal instruments such as the Public Safety Act (PSA) and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) have been used extensively to enable arbitrary detention and to suppress political dissent. Under this framework, the absence of visible protest has been portrayed as peace, even though it has largely been the result of intimidation and coercion. By early 2025, the civic and cultural space in IIoJK had shrunk to alarming levels. Journalists faced censorship and harassment.

Students and activists were monitored and detained. Educational institutions came under direct state control. In February 2025, several books were banned in schools and libraries, a move widely seen as an attempt to regulate ideas and narratives. The renewal of these bans on 5 August 2025 reinforced the perception that education and literature had become new fronts in the campaign to silence independent thought. These measures further deepened public alienation and mistrust. The Pahalgam attack in April 2025 occurred in an environment already saturated with rights violations. Rather than prompting restraint, the incident intensified existing patterns of raids, arrests and surveillance. Ordinary civilians found themselves increasingly vulnerable, with daily life marked by uncertainty and fear. The attack became another justification to normalize collective punishment and to further erode legal protections.

A decisive escalation followed the Red Fort blast in November 2025. The authorities launched a sweeping crackdown across IIOJK, transforming long-standing repression into an overt campaign of intimidation. Mass arrests were carried out, including of doctors, students and professionals with no connection to violence. Houses were raided or damaged and properties, often belonging to political activists, were seized. Entire neighborhoods were transformed into militarized zones, with families subjected to harassment and intimidation, making fear a central instrument of governance. Property confiscations accelerated across Pulwama, Shopian and Srinagar, targeting residents, business owners and farmers, further deepening socio-economic grievances.

Between September and December 2025, these developments revealed a clear pattern. This period also saw the emergence of “white-collar terrorism,” used as a tool to systematically pressure Kashmiris through legal, administrative and economic means. The violations were not isolated responses to security incidents. They reflected a deliberate strategy to suppress political expression, dismantle social cohesion and prevent any challenge to state authority. The erosion of civil liberties, the targeting of education and livelihoods and the use of collective punishment underscored the reality that IIOJK continues to be administered through force rather than consent.

This report examines the human rights situation during this period, documenting key trends, patterns and impacts on civilians. It affirms that Jammu and Kashmir remains a disputed territory under international law, where the people continue to be denied their rights to dignity, justice and security. The findings highlight the urgent need for accountability, international scrutiny and a rights-based approach grounded in dialogue rather than repression.

Methodology

This report employs a mixed- method approach, combining quantitative and qualitative analyses to provide a comprehensive overview of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh from September to December 2025. Data were systematically collected from verified media reports, local news outlets, press releases, X platform posts. Each September October November December Sep - Dec 2025 (Documented Incidents) Total Killings Custodial Killings Property Destroy ed / At tached Women Widowed Chidren Ophaned 5September – December 2025 documented incident, ranging from property seizures, arrests, CASOs to socio-economic and cultural developments, was cross- verified through multiple sources to ensure accuracy.

The analysis acknowledges that the intensity of measures is far beyond the cases included here; only those incidents with verifiable documentation are referenced. Thematic analyses were conducted to examine the broader implications of post-Pahalgam and post-Red Fort intensification measures on civilian life, economic activity, social cohesion. The report emphasizes empirical evidence, chronological sequencing, contextual interpretation to produce an objective, stakeholder-focused assessment of ongoing developments.

LADAKH ON BOIL: WHY A ONCESILENCED REGION ROSE IN PROTEST

Ladakh did not descend into unrest suddenly. The protests and violence witnessed in September 2025 were the outcome of longterm political exclusion, demographic manipulation and the denial of constitutional rights following India’s unilateral actions of 5 August 2019, when it revoked Jammu and Kashmir’s special status and reorganized the territory (HRW, 2025). When Ladakh was separated from the former State of Jammu and Kashmir and downgraded to a Union Territory without a legislature, its people were stripped of representative governance. Despite repeated assurances by New Delhi, statehood was never restored, nor were constitutional safeguards extended. What was presented as integration became, for Ladakhis, a loss of agency and dignity.

For years, the Indian government projected Ladakh as calm and cooperative. In reality, this socalled normalcy was enforced through administrative control and political silence. Decisions concerning land, employment and governance were centralized in Delhi. Local voices were marginalized. Peaceful appeals by community leaders went unanswered. By 2024, frustration had deepened across both Leh and Kargil, cutting across religious and regional lines. This alienation intensified in June 2025, when India introduced new domicile, reservation and language policies in Ladakh. Under the revised domicile rules, individuals with 15 years of continuous residence since 2019 could qualify as Ladakh domiciles by 2034 (The Statesman, 2025). Children of government officials who had served ten years and students studying locally for seven years were also included. These provisions raised fears of largescale nonnative settlement, threatening Ladakh’s fragile demographic balance. At the same time, the government announced 85 percent reservation for Scheduled Tribes in government jobs, even though over 97 percent of Ladakh’s population already belongs to ST communities, reinforcing perceptions of administrative control rather than genuine empowerment (Business Standard, 2025; Times of India, 2025).

Language policy further aggravated tensions. While English, Hindi, Urdu, Bhoti and Purgi were officially recognized, indigenous languages such as Shina, Balti, Brokskat and Ladakhi received limited institutional support. Critics argued that these measures, framed as inclusive reforms, were part of a broaderstrategy of cultural and demographic assimilation (Vision IAS, 2025).In response, the Leh Apex Body (LAB) and the Kargil Democratic Alliance (KDA) jointly submitted a 29page draft framework titled “Sixth Schedule Provisions and a Case for Statehood: Draft Framework for Ladakh” to the Indian Ministry of Home

Affairs. The document demanded full statehood, inclusion of Ladakh under the Sixth Schedule and the creation of a 30member Legislative Assembly, with 28 seats reserved for Scheduled Tribe communities. It also proposed replacing the existing Hill Development Councils with Autonomous District Councils and retaining the High Court of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh as a common judicial institution. LAB cochairman Chering Dorjay Lakruk stated that domicile and reservation issues had already been addressed and that the core demand remained constitutional protection and democratic restoration. The situation reached a breaking point on 24 September 2025. Indian forces opened fire on unarmed protesters in Leh, killing Tsewang Tharchin, a Kargil War veteran of the Ladakh Scouts, along with Rinchen Dadul (21), Stanzin Namgyal (24) and Jigmet Dorjay (25) (Reuters, 2025). At least four people were killed and dozens were injured when protesters demanding statehood and job quotas clashed with police, according to international reporting (AP News, 2025).

Nearly 100 civilians were injured, many by live ammunition and buckshot. In the aftermath, authorities imposed continuous curfews across Leh, Kargil, Zanskar, Nubra, Changtang, Padam, Drass and Lamayuru, while internet and mobile services were suspended, effectively sealing the region from external scrutiny (Reuters, 2025). Indian reporting confirmed that the clashes followed a shutdown called by the LAB youth wing and that protesters vandalized a BJP office and a police vehicle (AP News, 2025). Lieutenant Governor Kavinder Gupta described the unrest as a deliberate attempt to disturb peace and authorities blamed activist Sonam Wangchuk for “provocative” speeches that triggered the violence (Reuters, 2025). The protests were led by LAB and supported by KDA after a 35day hunger strike spearheaded by climate activist Sonam Wangchuk, two participants of which were hospitalized (The Week, 2025). Wangchuk later described the violence as an eruption of “Gen Z frustration,” driven by years of political exclusion and broken promises. Indian police arrested Wangchuk under the National Security Act (NSA) two days after the clashes, framing his arrest as linked to alleged incitement, a charge he denied, insisting that he called for calm and peaceful protest (NDTV, 2025). Dozens of others were arrested under preventive and criminal laws. Cremations of the victims took place under heavy security presence, reinforcing a climate of collective punishment and fear.

Political dialogue collapsed after the violence. LAB and KDA boycotted talks scheduled for 6 October 2025, resuming engagement only on 22 October after the government announced a judicial inquiry headed by a retired Supreme Court judge. Even then, the bodies insisted that no meaningful dialogue was possible without a judicial probe, release of detainees and general amnesty for those arrested after September 24. Tensions deepened further in December 2025, when five councillors of the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council (LAHDC), Kargil, challenged Lieutenant Governor Kavinder Gupta in the IIOJK High Court. The petition contested the nomination of Reyaz Ahmed Khan, a BJPaffiliated advocate, to a seat reserved for the principal religious minority. Citing the 2011 Census, which shows Kargil as 77 percent Muslim and 14.29 percent Buddhist, the councillors argued that Buddhists were the rightful minority and that the nomination violated the LAHDC Act, 1997. Observers warned that the move risked sowing divisions between Muslim and Buddhist communities, undermining their united struggle for rights (Times of India, 2025; TOI News Desk, 2025). Ladakh is on boil because democratic demands were ignored, constitutional protections were denied and peaceful dissent was met with bullets. The events of September to December 2025 exposed the failure of governance by coercion. Ladakh’s uprising is not a rejection of democracy; it is a demand for it.

EXTRAJUDICIAL KILLINGS IN IIOJK

Since 5 August 2019, when New Delhi revoked the special constitutional status of Jammu and Kashmir and bifurcated the region into two Union Territories, the human rights situation in IIOJK has deteriorated sharply. The political reorganisation was justified by the Indian state as necessary for stability and development. However, the periods following major flashpoints such as the Pahalgam terror attack of April 22, 2025 and the Red Fort blast in November 2025 reveal a pattern where security imperatives have repeatedly overshadowed legal norms, leading to widespread rights abuses, including extrajudicial killings and custodial deaths (Kashmir Media Service, 2025). 7September – December 2025 Pahalgam Attack and the Escalation of Security RepressionThe Pahalgam attack of 22 April 2025, which killed at least 26 civilians, most of them tourists, occurred at a time when Indian authorities were aggressively projecting IIOJK as having achieved full “normalcy.” Official narratives emphasised restored peace, record tourism and complete security control. The scale and location of the attack directly contradicted these claims.

In a region under intense militarisation and surveillance, the incident exposed serious inconsistencies in assertions of stability and raised questions about how such an attack could occur amid claims of peak security dominance (Reuters, 2025).Instead of transparent accountability, the attack was followed by Operation Sindoor, marked by widespread raids, mass detentions and punitive demolitions across Kashmir, particularly in Bandipora and Pulwama. Entire communities were targeted under the banner of counter-terrorism, blurring the line between security operations and collective punishment. Homes were destroyed without due process, civilians were detained on suspicion alone and reports of excessive force increased. The episode demonstrated how security incidents are used to justify intensified repression, with Kashmiri civilians becoming the primary targets of occupation policies rather than beneficiaries of protection or justice (KMS, 2025).

Custodial Killings as State Violence

The case of Firdous Ahmad Mir exemplifies how this securitised context has translated into gross violations of human rights. On 11 September 2025, Mir, a father of three from Hajin in Bandipora, was detained by troops of the Indian Army’s 13 Rashtriya Rifles and taken to a military camp. Days later, his tortured body was recovered from the River Jhelum, with visible injury marks indicating severe abuse in custody. His death sparked protests in Hajin, yet accountability remains unaddressed (KMS, 2025). Mir’s killing is not isolated. Instances in 2025 also include the discovery of a Kashmiri student’s body in Jammu city on 12 December 2025, with family and local reports alleging abduction, killing and the dumping of his remains in a location away from his hotel. Local protests erupted demanding an impartial investigation into the student’s death, highlighting how suspicions of state or statelinked involvement further eroded trust in lawful processes (Hindustan Times, 2025). These custodial deaths occur in a climate where security agencies operate with broad powers under laws such as the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) and the Public Safety Act (PSA), which critics argue enable arbitrary detention and shield perpetrators of abuse from accountability (KMS, 2025).

Red Fort Blast and Crackdown Dynamics

The Red Fort blast in Delhi on 10 November 2025, a deadly car explosion near a major national monument that killed and injured dozens, triggered yet another wave of heightened security measures. Indian authorities treated the incident as a terror attack under antiterror laws and the National Investigation Agency (NIA) took over the investigation. Subsequent raids and arrests included individuals from Kashmir, with Indian media reporting suspects linked to the blast and alleged supportive networks being apprehended in and around Kashmir (Times of India, 2025). In the aftermath, occupation forces expanded investigative operations into Kashmir, a development that risked conflating civilian populations with suspected terror modules. These actions, justified as necessary for national security, also contribute to an escalated environment of suspicion and repression, where due process and presumption of innocence can be sidelined, especially for Kashmiri residents (AP News, 2025).

Patterns of Killings and Accountability Deficits

Across these events, from postPahalgam operations to postRed Fort crackdowns, several patterns emerge.Securitization of Everyday Governance: Major security incidents are used to justify increased deployments and sweeping powers for forces, often at the expense of civil liberties. · Casualties Beyond Combatants: Civilians, whether detained suspiciously or caught in punitive responses, face lethal outcomes in custody or during operations labelled as antiterror measures. Lack of Independent Oversight: Investigations into custodial deaths and lethal force are often internal, lacking inde- pendent judicial or human rights oversight, undermining accountability. · Public Distrust and Resistance: These patterns reinforce distrust among Kashmiri communities towards state institu-tions, prompting protests and demands for accountability rather than compliance.

Impact on Civil Society and Political Dissent

Cases such as the custodial killing of Firdous Ahmad Mir and the suspicious death of Khalid Sharif Butt in Jammu illustrate how tragedy intertwines with political expression and resistance. Far from quelling unrest, such incidents deepen grievances among Kashmiris, who see them as part of a broader strategy to suppress dissent rather than address underlying political and constitutional issues. The recent waves of crackdown following the Pahalgam attack and the Red Fort blast reflect how security narratives can be employed to legitimise harsh measures, even when these measures violate basic human rights. In Kashmir’s context, where political aspirations and civil rights have long been contested, these patterns strengthen the argument that extrajudicial killings and custodial deaths are not aberrations, but symptomatic of a broader coercive governance framework (Hindustan Times, 2025).

Village Defence Guards as Enablers of Extrajudicial Violence

The Village Defence Guards (VDGs), a volunteer force historically notorious for involvement in the killing of civilians, represent a grave threat to the rule of law and civilian protection in the territory. Originally framed as a community-based security initiative, VDGs have instead functioned as armed auxiliaries operating with minimal oversight, blurred chains of command and near-total immunity. Their documented involvement in violent incidents against civilians has long raised concerns that these groups operate outside legal constraints, effectively normalising vigilantism under state patronage (The Hindu, 2025). Recent statements by the region’s Director General of Police, Nalin Prabhat, praising the “exceptional contribution” of more than 110 VDG members in past operations, mark a dangerous escalation. By publicly endorsing and promising rewards for their actions, the authorities are legitimising a paramilitary-style force already accused of targeting pro-freedom leaders, activists and ordinary Kashmiris (Kashmir Media Service, 2025). Human rights observers warn that such endorsement creates the structural conditions for extrajudicial killings, where lethal force is exercised without judicial scrutiny and later justified through security narratives.

The proposed integration of VDGs into formal policing structures further entrenches this risk. Rather than enhancing accountability, this move threatens to institutionalise a parallel force that operates at the margins of legality, where killings can be framed as counter-terror operations and shielded from investigation. In conflict settings globally, similar militia formations have been used as tools of deniability, enabling the state to distance itself from unlawful killings while retaining effective control over coercive violence. This development must also be viewed within the broader context of intensified militarisation in civilian and border areas of occupied Jammu and Kashmir. By empowering irregular armed groups and valorising their violence, the state signals that extrajudicial force is not only tolerated but rewarded. For civilians, particularly in rural and border districts, this translates into heightened vulnerability, pervasive fear and the erosion of any meaningful distinction between lawful security operations and unlawful executions. The continued expansion and legitimisation of VDGs thus deepens a culture of impunity and accelerates the normalisation of extrajudicial killings in the occupied territory.

ARBITRARY DETENTIONS IN IIOJK

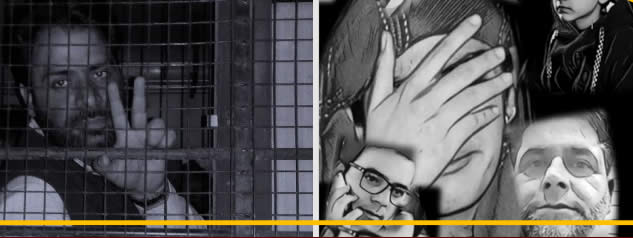

From September to December 2025, detentions under arbitrary and preventive laws escalated sharply IIOJK. Civilians, professionals, activists and even elected representatives were arrested under laws such as the Public Safety Act (PSA) and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). These laws, intended for national security, were repeatedly misused to suppress dissent and silence critical voices without credible evidence or due process. The pattern of detentions during this period demonstrates both the breadth and arbitrariness of the Indian state’s approach to civil liberties in the territory. 9September – December 2025

One of the most prominent cases during this period was that of Imtiyaz Ahmad Ganie from Chee village in Anantnag. Ganie, a34yearold tractor driver with no history of violent activity, was arrested in April 2024 under PSA. The Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh High Court quashed his detention in September 2025, noting a mistake of identity and lack of independent reasoning by the detaining authority. Despite the ruling, Ganie remained in custody. He missed the birth of his son and the funeral of his mother because he was not released even temporarily, illustrating the severe human cost of prolonged arbitrary detention (Cross Town News, 2025).

The High Court’s intervention in Ganie’s case points to a broader legal recognition that PSA detentions are often based on superficial dossiers and poor adjudication. The court described the detention order as “shameless” and criticized authorities for failing to apply their mind in issuing the order, a phrase that resonated with many legal observers reviewing PSA practices (NewsArenaIndia, 2025).

September October November December Arbitrary Detentions in IIoJK

Sepetember - December 2025 (Documented Cases) Detentions were not limited to individuals like Ganie. In October 2025, the High Court struck down a PSA order against Mohd. Kalu, noting multiple procedural flaws, including failure to inform the detainee of his rights and judging the detention order to be a mere reproduction of a police dossier without independent analysis (Cross Town News, 2025). Another quashing occurred in November 2025, when the court annulled the PSA detention of a 27yearold Pulwama resident, stating that the grounds were based on stale FIRs that lacked any live connection to current security concerns, reflecting a longstanding judicial concern about procedural abuse (KNS Kashmir, 2025).

This judicial criticism shows a fundamental flaw: in many PSA detentions, the detaining authority relies on old or vague allegations, sometimes years old, to justify preventive custody. In policing parlance, this “copy–paste” approach produces orders that are legally unsustainable but remain in effect unless challenged in court (Kashmir Times, 2025). The surge in detentions also coincided with intensified arrests under the stringent UAPA. According to government data presented in the Indian Parliament, IIOJK accounted for 42% of all UAPA arrests in India in 2023, with 1,206 out of 2,914arrests made in Jammu and Kashmir despite a conviction rate below 1% for that year (NDTV, 2025). This stark imbalance between arrests and convictions underscores a systemic misuse of antiterror laws to detain individuals on minimal evidence.

Many of those detained under UAPA and PSA were professionals and individuals with no proven links to violence. For instance, reports from the latter part of 2025 described arrests of Kashmiri doctors and civilians in Punjab and New Delhi under pretexts related to wider security cases, raising concerns that charges were being used to stigmatize educated Kashmiris and frame them as security threats without transparent evidence. These actions fueled a sense that the legal system was being stretched to silence voices perceived as too visible or influential (Times of India, 2025).

The arbitrary nature of detentions was further highlighted by routine cordonandsearch operations (CASOs) conducted during these months. According to civil society statements, hundreds of civilians were detained during these operations, many booked under preventive laws rather than for specific criminal conduct. Property was damaged or seized during raids, families were harassed and communities were left reeling in the absence of credible justification for such broad police actions, a form of collective punishment rather than targeted law enforcement (Democratic Freedom Party, 2025).

Beyond individual cases, the sheer volume of detentions drew legal and political criticism. In other instances, High Court rulings throughout 2025 repeatedly found PSA orders to be based on nonapplication of mind, procedural lapses and delays that undermined any legitimate claim of imminent threat. Such rulings affirm that detaining authorities often base orders on police dossiers filled with vague assertions and recycled allegations rather than facts demonstrating a real threat to public order (TheWeek, 2025). Another worrying development during this period was the detention of public figures, including an Aam Aadmi Party legislator in September 2025, who was held under PSA on broad charges of disrupting public order, a signal that the government was willing to use preventive detention against political actors, not only civilians (Reddit news reporting noted this political detention, 2025).

The period from September to December 2025 saw a sharpened pattern of arbitrary detentions in IIOJK. Authorities aggressively used PSA and UAPA to detain individuals with minimal or stale evidence. Courts frequently quashed these detentions, underscoring their legal infirmity, yet enforcement remained stubbornly unchanged. Arrests under UAPA dominated national figures despite low conviction rates and preventive detention orders were based on deficient dossiers and procedural shortcuts. This environment has raised fear and uncertainty across Kashmir’s civil society. Families are torn apart, communities are traumatized and the criminal justice system is co-opted into projecting repression as security. The detentions from September to December 2025 demonstrate a pattern where the law is wielded not to protect citizens but to suppress dissent and silence critics.

In this context, the use of preventive detention in IIOJK is less about protecting public order and more about consolidating control through coercion, intimidation and a systemic denial of basic legal rights, a trend that demands urgent scrutiny and reform. 11September – December 2025

Digital Detention Becomes the New Norm in IIOJK

The latest iteration of this systemic repression is the imposition of GPS-enabled ankle monitors on undertrial detainees, a practice that transforms legal release into continued surveillance and control. The case of Mukhtar Ahmed, a resident of Poonch, illustrates this shift vividly. Arrested on charges widely reported as fabricated, he was granted bail by the Court of the Principal District & Sessions Judge, Udhampur. However, the court mandated the installation of a GPS tracking anklet as a bail condition. This device continuously transmits his location to authorities, effectively turning him into a monitored prisoner, despite his legal entitlement to freedom. Reports suggest that similar devices have been imposed on numerous undertrial detainees across IIOJK since November 2023, when GPS tracking was first introduced in the region by J&K Police, marking a new dimension of control over an already policed population.

This “detention after detention” effect is reinforced by the broader surveillance ecosystem in IIOJK. Kashmiris routinely face phone confiscations, online monitoring, biometric data collection for basic services and pervasive military and police checkpoints. In this context, a GPS anklet becomes not an isolated measure but a digital extension of incarceration, reinforcing a continuous state of restriction. The device functions as a permanent reminder that freedom outside prison walls is conditional, monitored and ultimately controlled by the state. This practice raises profound concerns. Under Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), every individual is presumed innocent until proven guilty. GPS monitoring of undertrial detainees violates this principle, creating a presumption of guilt by imposing continuous restrictions on movement and privacy. Articles 9 and 12 of the ICCPR protect against arbitrary deprivation of liberty and safeguard the right to freedom of movement. Continuous electronic monitoring constitutes a direct infringement of both rights, especially when applied without clear legal safeguards or proportionality.

Globally, electronic monitoring is meant to serve as an alternative to incarceration for convicted, low-risk individuals. In IIOJK, however, the technology is weaponized against politically vulnerable populations, targeting civilians accused on dubious grounds. The UN Human Rights Committee has emphasized that surveillance measures must be necessary, proportionate and non-discriminatory; GPS tracking in IIOJK fails on all three counts. In effect, GPS tracking transforms detention into a state-sanctioned, technology-driven continuum of confinement. Individuals leave physical prisons only to enter a digital one. Movement is monitored, privacy is violated and freedom becomes an illusion. The practice exemplifies a troubling evolution of occupation strategies, where control shifts seamlessly from tangible detention to invisible, technologically enforced surveillance.

CORDON-AND-SEARCH OPERATIONS IN IIOJK: A SIEGE ON CIVILIANS AND WOMEN

Cordon-and-search operations (CASOs) in IIOJK have increasingly evolved from purported counter-terrorism measures into instruments of systemic intimidation and collective punishment. Since the abrogation of Articles 370 and 35A in August 2019, these operations have become normalized under Indian security policy, targeting civilians without due process and violating core legal protections under both international humanitarian law and human rights law (The Hindu, 2025). CASOs are routinely conducted without judicial warrants or accountability mechanisms, resulting in home invasions, prolonged confinement, arbitrary arrests and psychological coercion. Between September and November 2025, at least 41 cordon-and-search operations (CASOs) were carried out across IIoJK, including 19 in September, 10 in October and 12 in November, spanning multiple districts such as Kathua, Samba, Rajouri, Anantnag, Kupwara, Udhampur, Poonch, Srinagar, Ganderbal and Jammu.

This pattern reflects a deliberate and systematic campaign of surveillance and control over the civilian population. The indiscriminate nature of CASOs undermines the principles of necessity, proportionality and distinction. Intelligence inputs triggering operations are often vague or outdated, leading to mass searches, entire neighborhoods being sealed off and residents subjected to threats, humiliation and invasive scrutiny. The gendered consequences are particularly pronounced: Kashmiri women, expected to inhabit the domestic sphere as a safe space, are instead exposed to harassment, intimidation and trauma. Human rights defenders report that women routinely experience dawn or late-night raids while sleeping, dressing, or nursing children, with verbal threats and mockery a frequent part of these operations (The Wire, 2025).

Testimonies from across IIOJK indicate that women face intrusive searches, verbal degradation and threats that disrupt daily life, limit education and employment opportunities and perpetuate long-term social isolation.The case of Sameera, a 17-year- old student from Village Khanak Nursery, Kathua, exemplifies the coercive power of CASOs. On 25 November 2025, Border Security Force personnel, preceded by local police, forcibly entered her home during a CASO. Her belongings were thrown about and she was directly threatened by the troops, who implied potential sexual assault. When her mother attempted to intervene, she too was threatened. The operation instilled fear so profound that Sameera’s parents instructed her to stop attending college and remain at home. This illustrates how CASOs exercise control without formal arrests by curtailing education, mobility and aspirations (Rising Kashmir, 2025).

Arbitrary arrests during CASOs have increasingly involved Indian agencies such as the State Investigation Agency (SIA) and the National Investigation Agency (NIA). These agencies target women linked to political or kin relations associated with the Kashmiri struggle for self-determination. Prominent examples include Dukhtaran-e-Millat leaders Aasiya Andrabi, Fehmeeda Sof and Nahida Nasreen, who remain detained under stringent laws. Other cases, such as Shahzada Akhtar and her husband Dr.Umer Farooq Bhat, arrested during a CASO in Kulgam, highlight the systematic targeting of women under so-called “blacklaws” (Hindustan Times, 2025). Since 2017, over three dozen women, married and unmarried, have languished in detention, reflecting the gendered and punitive dimension of CASOs.

CASOs also function as a threshold into a wider regime of repression. They blur the lines between investigation and punishment, criminalizing civilians arbitrarily and disproportionately. Testimonies from Kathua, as well as other districts, indicate that fear generated by CASOs is intended to discipline behavior rather than gather intelligence. Women’s testimonies repeatedly describe fear of recurrence, leading families to withdraw daughters from education and public life, thereby achieving the intended suppression of mobility and autonomy without formal arrests. The psychological and social impact of CASOs is profound. Victims report heightened anxiety, trauma and constrained family life. Educational disruption and curbed mobility disproportionately affect young women, while social isolation is exacerbated when male family members are arbitrarily detained or when family properties are confiscated. CASOs often operate alongside draconian laws such as PSA and UAPA, which facilitate long-term arbitrary detention. For instance, citizens in Kathua, Anantnag and Srinagar have reported arrests under these laws immediately following CASOs in September–December 2025, linking searches directly to punitive detention strategies (NDTV, 2025).

The intent behind CASOs extends beyond tactical security objectives. By targeting women and families, these operations weaponize domestic spaces to instill fear, curtail social participation and silence dissent. The operation in Sameera’s home, alongside similar raids in Kathua, Rajouri and Anantnag, demonstrates that CASOs are systematically deployed to assert control over the civilian population, particularly women. International norms prohibiting collective punishment, intrusion into family life and gender-based abuse are repeatedly violated (Amnesty International, 2025). Despite widespread documentation of abuses, CASOs remain underreported due to social stigma, fear of retaliation and lack of credible complaint mechanisms. Local women emphasize that silence should not be mistaken for consent; rather, it is a survival strategy. Testimonies collected from Kupwara, Udhampur and Poonch show consistent patterns of verbal threats, humiliation and intimidation, reflecting the routine nature of CASOs as tools of governance by fear (The Wire, 2025).

CASOs in IIOJK are neither routine security measures nor proportional law enforcement operations. They are instruments of coercion, designed to discipline civilian behavior, target women and suppress political and social participation. From intrusive dawn raids in Kathua to operations across Anantnag, Kupwara and Srinagar between September and December 2025, the evidence points to a systematic and gendered abuse of power. International attention is urgently required to address the widespread violations, ensure accountability and restore the dignity and security of Kashmiri women living under occupation.

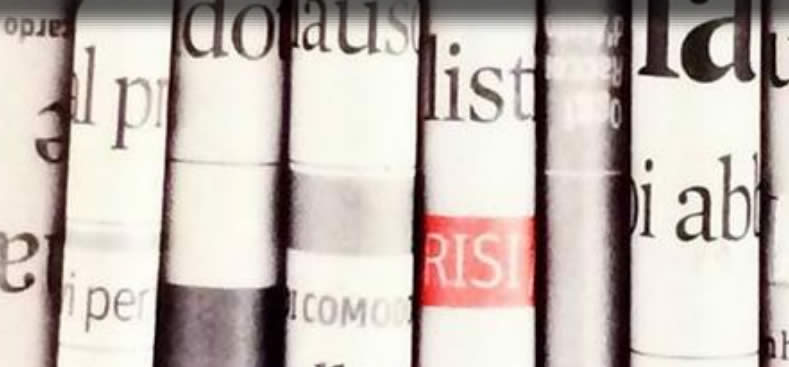

THE CRISIS OF JOURNALISM IN IIOJK

The collapse of journalism in Jammu and Kashmir reflects a deeper democratic breakdown. Press freedom in the region has declined alongside political disenfranchisement, legal exceptionalism and expanded security governance. Journalism no longer functions as an independent institution. It operates as a constrained activity under constant risk. Data trends, employment losses and case trajectories demonstrate a deliberate restructuring of the media ecosystem.

Quantitative Patterns of Repression and Legal Exposure

Legal pressure against journalists follows a measurable pattern. Between August 2019 and early 2025, at least 75 journalists in Jammu and Kashmir faced police questioning, formal cases, or prolonged investigations. Of these, over 30 were subjected to repeated summons, often without charge sheets. At least 18 journalists experienced detention or preventive custody lasting from days to several months.

In 2025 alone, multiple cases reinforced this trend. Journalist Irfan Mehraj remained incarcerated under terrorism-related charges linked to civil society documentation work. His detention extended beyond 600 days by early 2025. Journalist Majid Hyderi continued to face legal uncertainty, professional restrictions and repeated questioning following earlier arrests. Aasif Sultan, previously imprisoned for years, remained under surveillance and faced barriers to full professional reintegration. In IIoJK, the revolving-door arrest model persists. Authorities release journalists on bail only to re-arrest them under new provisions. This pattern applied to Fahad Shah, who faced multiple cases across different police stations before prolonged incarceration disrupted his newsroom entirely.

Travel restrictions constitute another quantifiable control mechanism. Since 2019, at least 12 journalists from Jammu and Kashmir have been stopped from traveling abroad despite valid documentation. Sanna Irshad Mattoo faced repeated airport stops, including in 2022 and lingering administrative scrutiny through subsequent years, affecting assignments and income. Digital expression also attracts criminal liability. Between 2020 and 2024, more than 20 journalists faced cybercrime-related questioning for social media posts, archived images, or commentary. Even reposting content triggered police action. These measures institutionalized self-censorship. Journalists now assess legal risk before publishing basic facts. 15September – December 2025 The cumulative impact is measurable. Surveys conducted by local journalist bodies show that over 65 percent of journalists in Kashmir avoid reporting on security operations and over 70 percent avoid human rights documentation. Fear, not editorial judgment, now shapes coverage.

Economic Collapse, Employment Loss and Professional Exit

Economic strangulation remains the most effective instrument of media control. Government advertising historically accounted for 60 to 80 percent of revenue for local newspapers in Jammu and Kashmir. After 2019, ad allocation shifted sharply. Independent outlets experienced sudden withdrawal without explanation. Between 2020 and 2024, at least 15 local newspapers ceased regular publication. Print circulation dropped dramatically. Newspapers that once printed 25,000–30,000 copies daily now print fewer than 7,000. Some reduced publication to weekly editions. Others stopped entirely. Employment data reveals the scale of collapse. Conservative estimates indicate that over 350 journalism jobs disappeared in the region since 2019. These included reporters, sub-editors, photographers, designers and distribution workers. District-level bureaus shut down. Rural reporting nearly vanished. Wages declined sharply. Entry-level journalists now earn 40–60 percent less than pre-2019 averages. Freelancers often receive no contracts, insurance, or legal protection. Payment delays of three to six months have become common. The shutdown and prolonged disruption of platforms such as The Kashmir Walla illustrate this economic coercion. Raids, seizures and ad denial forced staff layoffs. Investigative reporting halted. Audience reach collapsed.

Television and radio outlets also suffered. Sponsorship dried up. National advertisers avoided association with politically sensitive outlets. Private sector fear reinforced state pressure. Journalism education mirrors this decline. Enrollment data from universities in Srinagar and Jammu shows a drop from over 100 annual graduates in the early 2010s to 25–30 graduates today. Female enrollment declined even more steeply due to safety concerns and lack of prospects. This decline feeds a talent drain. Experienced journalists migrate to Delhi or exit the profession entirely. Younger reporters lack mentorship. Institutional memory erodes. Newsrooms lose depth and continuity. Quantitative indicators reflect this erosion. Public access to investigative reporting declined sharply. In 2024, fewer than 10 in-depth investigative stories on governance or rights issues emerged from local outlets, compared to dozens annually before 2019.

Red Fort Blast Aftermath: Escalating State Intimidation Against Journalists in

After the Red Fort blast, state action against journalists in Jammu and Kashmir escalated from arrests and interrogations to overt acts of intimidation designed to send a chilling message across the media landscape. A stark illustration of this trend is the case of journalist Arafat Ahmad Dar. Following the incident, authorities demolished his residential house in the presence of a significant police and security contingent, framing the action as an administrative measure. In reality, the demolition, carried out without any transparent judicial process, functioned as punitive retaliation. Beyond material loss, it symbolically erased a journalist’s identity, signaling that professional independence could invite personal and collective punishment. The immediate consequences were profound: reporting halted, sources withdrew and colleagues curtailed engagement with sensitivestories. Data collected from journalist associations indicates that after such high-profile demolitions involving media workers, newsroom output on security and human rights issues declined by more than 40 percent in the ensuing months, while coverage shifted toward non-political and less contentious topics.

The intimidation of Arafat Ahmad Dar was not an isolated act. On December 16, 2025, the Jammu office of Kashmir Times, one of the region’s oldest independent newspapers, was raided by authorities, documents were seized and the premises were sealed. Founded in 1954 by Ved Bhasin and led after 2015 by his daughter Anuradha Bhasin, the newspaper had long chronicled the lives, struggles and aspirations of Kashmiris with unflinching honesty. Post-2019, following the abrogation of Articles 370 and 35A on August 5, 2019, the publication became a prime target for state repression. Communications blackouts, enforced under the longest internet shutdown in a democracy, severely restricted journalistic activity, while the 2020 Media Policy institutionalized censorship, allowing authorities to label reporting as “fake news” and withhold government advertisements from dissenting outlets. Multiple FIRs were filed against Anuradha Bhasin, including charges of “inciting disaffection” for reporting protests factually. Offices had been forcibly closed before: the Srinagar office in 2020 and multiple raids on the Jammu office in the years following 2019 illustrate a deliberate strategy of administrative and legal pressure to bankrupt and isolate independent media.

The connection between the demolition of Dar’s home and the Kashmir Times raids lies in the message conveyed: journalism itself has become a liability. These measures are not isolated incidents but part of a systematic campaign to suppress dissenting voices and monopolize the narrative. The cumulative effect on media operations has been devastating. Fear, self-censorship and structural intimidation have become normative. Editors report that reporters increasingly avoid security, political, or rights- based coverage, prioritizing safety over public interest. The targeting of both individual journalists and institutional media, through home demolitions, raids, FIRs and travel restrictions, demonstrates a coordinated strategy to convert independent reporting into a liability rather than a democratic function.

The cases of Arafat Ahmad Dar and Kashmir Times highlight the transformation of press freedom in Jammu and Kashmir: from harassment and legal action to structural intimidation and narrative control. By linking professional activity to personal risk and material loss, authorities have created a pervasive climate of fear, ensuring silence is the rational response. In such an environment, the act of journalism is no longer a pursuit of truth but a potential avenue for reprisal, eroding both the independence of the press and the democratic accountability it is meant to safeguard.

DIGITAL CENSORSHIP AND INFORMATION CONTROL AFTER OPERATION SINDOOR

The digital space has undergone systematic contraction following Operation Sindoor. What began as a so-called security operation after the Pahalgam attack, which killed 26 people, including 25 tourists and one resident, quickly expanded into a broader strategy of information control. Measures taken after the operation moved beyond physical surveillance and cordon operations and entered the realm of online expression and digital visibility (Jammu and Kashmir Police Briefing, 2024). Following Operation Sindoor, X (formerly Twitter) confirmed that over 8,000 accounts were withheld in India, including numerous accounts linked to IIOJK. X stated that these actions were taken in response to executive orders issued by the Indian government. The company publicly acknowledged that it disagreed with the orders but complied due to the risk of heavy financial penalties and the possibility of imprisonment of local employees under domestic law (X Transparency Statement, 2024).

X further clarified that the blocking was geographically restricted, meaning that the accounts remained visible outside India but inaccessible within India and IIOJK. The company stated that this form of compliance was adopted to avoid complete platform disruption while still adhering to binding legal directives, a practice increasingly used in jurisdictions with expansive executive powers over intermediaries (X Global Affairs Update, 2024). In its public disclosure, X stated that in most cases, the authorities did not specify which posts violated Indian law. In a significant number of cases, no evidence or justification was provided. Entire accounts were withheld instead of individual posts. X warned that such actions amount to censorship of both existing and future content, undermining the fundamental right to freedom of expression (X Legal Compliance Note, 2024). Despite these concerns, X confirmed that it is legally barred from publishing the government’s takedown orders. Indian law restricts intermediaries from disclosing executive blocking directions, preventing public scrutiny and meaningful legal challenge. This secrecy leaves affected users without clarity, notice, or effective remedy (Information Technology Act Compliance Framework, 2023).

Journalists and independent media platforms reporting on IIOJK were disproportionately affected. Accounts withheld include Anuradha Bhasin, Managing Editor of Kashmir Times; Free Press Kashmir; The Kashmiriyat; Maktoob Media; and Muzzamil Jaleel, Deputy Editor at The Indian Express. Force Magazine also had content restricted, including a video by editor Pravin Sawhney (Press Freedom Tracker India, 2024). Each withheld account displayed the same message: “Withheld in India in response to a legal demand.” No account-specific explanation or violation notice was provided. This uniformity concealed the absence of due process and masked the selective targeting of Kashmir-focused reporting (Internet Freedom Foundation Analysis, 2024). Maktoob Media stated that it received no prior notice, no legal citation and no explanation for the withholding. Its Founding Editor, Aslah Kayyalakkath, confirmed that no specific post was flagged. Maktoob’s reporting included documentation of over 64 hate speeches, coverage of lynchings and early reporting from conflict-affected areas such as Poonch (Maktoob Media Statement, 2024).

The platform also published verified profiles of civilians and security personnel killed in violence, including Lt. Vinay Narwal and Adil Shah, a civilian pony rider. Maktoob stated its intention to challenge the restriction through legal channels, despite acknowledging limited remedies under current law (Maktoob Legal Notice, 2024). Individual digital creators were also targeted. Arpit Sharma, a content creator, had his account withheld after posting material that challenged misinformation, questioned security lapses and criticised communal mobilisation after Operation Sindoor. He stated that his content contained no incitement or unlawful material (Personal Affidavit, 2024). Other platforms experienced similar restrictions. The Instagram account “MO of Everything” was reportedly disabled, indicating cross-platform coordination. This reflected a broader enforcement pattern affecting multiple intermediaries simultaneously (Digital Rights Monitoring Group, 2024). 17September – December 2025

These platform-level actions coincided with a formal advisory issued by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. The advisory directed OTT platforms, streaming services, media platforms and intermediaries to discontinue access to specified digital content. The grounds cited were sovereignty, territorial integrity and security of the State (MIB Advisory, 2024). Following the advisory, 16 YouTube channels were blocked and multiple entertainment and drama channels became inaccessible within India. A formal communication was also sent to an international broadcaster objecting to its editorial language, reflecting increased state involvement in narrative policing (Media Policy Review, 2024). By September 2025, these measures had created a digital environment in IIOJK marked by executive opacity, platform compliance under coercion and absence of effective remedies. Legal challenges remained constrained due to statutory limitations on contesting executive orders (Civil Liberties Assessment, 2025).

Preventive Detention, Speech Regulation and the Architecture of Silence in IIOJK

The digital crackdown after Operation Sindoor unfolded alongside an intensified use of preventive detention under the Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act (PSA), 1978. After the Pahalgam attack, 90 individuals were booked under PSA, while approximately 2,800 people were rounded up for questioning or preventive detention (Home Department Data, 2024). The PSA allows detention for up to two years without trial, without filing a charge sheet and without applying ordinary bail standards. Detention orders are executive in nature, with minimal judicial scrutiny, making the law one of the most far-reaching preventive detention regimes in India (Amnesty International, 2023).

Senior police officials confirmed that the post-Operation Sindoor crackdown targeted individuals described as over-ground workers, sympathisers, or persons with an “inimical mindset.” The Inspector General of Police, Kashmir Zone, stated that the operation would be further intensified (IGP Kashmir Press Statement, 2024). Legal scholars reviewing over 100 PSA dossiers across a decade identified recurring patterns. Many detainees had prior detentions from 2016–2017. Several were minors at the time of earlier detentions. In numerous cases, no fresh FIRs existed (Independent Legal Audit, 2024). PSA dossiers frequently relied on recycled allegations, quashed cases and decade-old police records. Vague phrases such as “threat to public order” appeared without evidentiary detail, weakening any claim of necessity or proportionality (Supreme Court Bar Association Review, 2023).

Families of detainees often reported that they did not receive full PSA dossiers. Many avoided speaking to journalists due to fear of reprisals, reinforcing silence and under-reporting (Human Rights Defenders Collective, 2024). Majid Ali (name changed), aged 21, was detained under PSA on 23 April. His first detention occurred in 2016, when he was 12 years old. He was later detained at the Joint Interrogation Centre in 2022 before being sent to Kot Bhalwal Jail under a two- year PSA order (Case File Review, 2024). Other detainees include Nadeem, 23, detained on a 2017 record; Faizan, 19, booked after a 2021 Facebook post; Ishfaq, 25, detained based on a 2016 record; Rashid, 28, detained in 2016 and 2019; and Yawar, 22, detained based on juvenile records (Detention Monitoring Report, 2024).

The case of Rehmatullah Padder, a 30-year-old environmental activist from Doda, illustrates the link between speech and detention. Arrested on 9 November 2024, his PSA dossier accused him of “anti-State activities” and cited his oratory skills and social media presence (PSA Dossier Extract, 2024). Parallel to detention, speech control has been formalised through Circular No. 09-JK(GAD) issued on 24 March 2023. The circular enforces social-media restrictions on government employees under the Jammu and Kashmir Employees Conduct Rules, 1971 (GAD Circular, 2023). Invoking Article 19(2), the rules prohibit employees from discussing or criticising government policy or action on social media. Violations attract penalties under the J&K Civil Services Rules, 1956, including dismissal from service (Conduct Rules Commentary, 2023). By September 2025, these legal, administrative and digital measures operated together as a coherent architecture of silence in IIOJK. After Operation Sindoor, speech became conditional, visibility became punishable and silence became enforced policy (Civil Society Joint Assessment, 2025).

CONFISCATION AND ATTACHMENT OF PROPERTIES IN IIOJK: A SYSTEMATIC CAMPAIGN

Property confiscation and attachment in IIOJK has become a core instrument of governance and control. What Indian authorities frame as lawful enforcement under anti-terror or counter-insurgency laws is increasingly being used as a tool to punish political dissent, control communities and target families associated with freedom struggle movements. These actions have extended far beyond isolated cases, forming a pattern of systematic property seizures across residential, commercial and agricultural holdings, often without due process, judicial oversight, or transparency. The impact is not limited to individual economic loss. Entire households are disrupted, social leadership weakened and communities terrorized. The legal mechanisms invoked, including the UAPA and provisions under the Criminal Procedure Code, have facilitated large-scale confiscations, often based on alleged associations rather than proven acts (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights [OHCHR], 2019). This has allowed authorities to convert suspicion into structural punishment, creating an environment in which ordinary citizens face coercion through economic deprivation.

Scale, Scope and Legal Mechanisms of Property Seizures

The scope of property confiscation in IIOJK is substantial. Since 2019, hundreds of properties have been seized under the pretext of being linked to freedom fighters or their support networks. For instance, in 2025, authorities attached the house of a resident in Udhampur district (Monitoring Desk, 2025). On 14 November 2025, the ancestral property of Hurriyat leader Mohammad Yaqoob Sheikh in Pulwama was confiscated. On the same day, the property of former bar president Mian Qayoom in Srinagar was seized. These actions are often justified as “security enforcement” or “anti-terror measures,” but the scale and systematic application indicate broader objectives of intimidation (Monitoring Desk, 2025).

The legal framework facilitating these actions primarily relies on the UAPA, which allows the attachment of property alleged to be linked to unlawful activity. Section 8 and Section 25 empower agencies to freeze, attach, or forfeit assets purportedly used to support “freedom fighters” or organisations resisting state policies. For example, in 2025, the State Investigation Agency (SIA) and Jammu and Kashmir Police reported the attachment of 124 properties across 86 locations in IIOJK, most of which were linked to individuals or groups considered politically or ideologically opposed to New Delhi’s administration (Kashmir Life, 2025). While authorities claim these seizures are aimed at disrupting funding networks, in practice, many affected properties are residential homes or commercial establishments that are economically vital to families.

High-value seizures further illustrate the scale and strategic use of property confiscation. In 2022, assets worth hundreds of crores of rupees belonging to organisations considered freedom-supporting were seized across districts such as Baramulla, Bandipora, Ganderbal and Kupwara (NDTV, 2022). Similarly, in March 2019, the Enforcement Directorate attached 13 properties worth over INR 1.22 crore linked to associates of freedom fighters, followed by additional seizures exceeding INR 6.2 crore (Kashmir Times, 2023). These high-value confiscations send both a political and economic message: that families and communities associated with freedom struggle are vulnerable to state intervention at any time.

pattern extends to agricultural and rural land, a critical source of livelihood in Kashmir. In Ramban district, authorities attached over 1.25 acres of farmland linked to individuals accused of political opposition, prohibiting its sale or transfer under UAPA provisions (India Today, 2025). Such seizures disrupt local economies, threaten food security and destabilize entire villages dependent on agriculture.

Patterns, Data and Socioeconomic Consequences

The patterns of property attachment and confiscation in IIOJK reveal systematic targeting rather than incidental law enforcement. Families of freedom fighters, political activists and those ideologically opposed to occupation policies are disproportionately affected. Case studies illustrate the scope and methodology: · Guree Village, Pulwama (2025): The two-storey home of Adil Thoker was demolished in a controlled explosion, leaving only the kitchen partially intact. Neighbors were forcibly relocated and Thoker’s father, brother and cousins were detained (Bilal Kuchay, NPR, 2025).

· Murran Village, Pulwama (2025): The home of Ahsan Ul Haq Sheikh was demolished at night, causing collateral damage to neighboring homes and terrorizing the local community (Bilal Kuchay, NPR, 2025). · Pulwama (2025): Asif Sheikh’s family home was destroyed after livestock were locked in sheds and doors and win-dows forcibly blown apart (Bilal Kuchay, NPR, 2025). · Kathua (25 November 2025): Sameera, a 17-year-old student, described the storming of her house during a siege-and- search operation, leaving her and her family in fear for their safety. Her parents forced her to discontinue college to avoid harassment (Kashmir Media Service, 2025). · Kulgam (2025): Shahzada Akhtar and her husband, Dr. Umer Farooq Bhat, were arrested during a house siege that encircled the property entirely, demonstrating the combination of intimidation, detention and property control.

These cases illustrate a broader strategy where suspicion or association, rather than legal conviction, triggers property seizure, effectively punishing entire families and communities. The approach amounts to structural and collective coercion, in which property becomes a tool for social and political control (OHCHR, 2019). The socioeconomic consequences are profound. Confiscated homes, businesses and farmland remove the economic base of families, disrupt education and livelihood and force communities into compliance. Women, in particular, bear a gendered impact, as they are often responsible for household management and face threats to personal safety during these operations. The cumulative effect is an environment of fear, economic vulnerability and social marginalization.

By framing these seizures under counter-terrorism law and security narratives, authorities reduce scrutiny, limit avenues for appeal and normalize a culture of coercion. Neighborhoods are locked down, possessions destroyed or damaged and families detained or threatened. The result is a de facto regime of collective punishment masked as legitimate law enforcement. Furthermore, the targeting of economic hubs such as shops, orchards and warehouses compounds the impact. Property attached in Hyderpora and HMT in previous years serves as precedents for the systematic extension of this strategy to multiple districts, reinforcing the perception of arbitrary and punitive governance.

The confiscation and attachment of properties in IIOJK represent more than isolated law enforcement; they constitute a systematic tool of occupation and social control. Between 2019 and 2025, hundreds of properties,including residential homes, commercial spaces and agricultural land, have been seized, often on the basis of association with freedom fighters, political dissent, or ideological affiliation rather than demonstrable criminal acts. These operations are carried out under broad statutory provisions, frequently with minimal judicial oversight and combined with house demolitions, forced detentions and intimidation. The social and economic consequences of this campaign are severe. Families lose homes, livelihoods and inheritance; women and children face disproportionate vulnerability; and communities are left in a permanent state of fear. The strategic pattern, documented across Udhampur, Pulwama, Srinagar, Kathua, Kulgam and Ramban, underscores that property attachment is deployed not just as law enforcement but as a tool for political, social and economic subjugation.

The use of property confiscation and attachment in IIOJK raises pressing concerns under domestic and international legal frameworks. Beyond immediate economic impact, these actions erode the fabric of civil society, limit mobility and education and enforce compliance through intimidation. Understanding these measures as a systematic campaign, rather than isolated actions, is critical for highlighting the scale of human rights challenges in the region and for informing international attention, advocacy and legal scrutiny (OHCHR, 2019; Kashmir Life, 2025).

Bulldozer and Demolition Policy in IIOJK: A Tool of Punitive Governance

The bulldozer-driven demolitions have become a systematic method of control in IIoJK. Authorities claim these operations target “terror infrastructure” or enforce law and order. In practice, however, they overwhelmingly target the properties of families associated with freedom fighters, political activists, or dissenting voices. The policy goes beyond law enforcement. Itis punitive. It is designed to intimidate, coerce and terrorize communities. The demolition policy is implemented under the guise of anti-terrorism laws, like UAPA and local administrative orders. Yet, many of the properties destroyed have no confirmed links to armed activity. Entire households are affected, including women, children and elderly family members. The operations often occur without prior notice, judicial orders, or any transparent process. Residents are sometimes forcibly removed from their homes before the demolition.

21September – December 2025 One of the most cited cases is Adil Thoker’s house in Guree, Pulwama. On 26 April 2025, occupation forces demolished his two-storey house using explosives. Neighbors were moved a hundred meters away for safety, but Thoker’s father, brother and cousins were detained. Only the kitchen remained partially intact. Local reports indicate this demolition was part of the post- Pahalgam crackdown, although Thoker’s extended family had no confirmed role in the incident (Bilal Kuchay, NPR, 2025). This case demonstrates how demolitions serve as collective punishment rather than targeted counterterrorism. In another Pulwama village, the home of Asif Sheikh was destroyed. Occupation forces tied the family’s livestock into sheds, ordered residents to cover their ears and detonated explosives that shattered doors and windows. Nearby houses also suffered structural damage. The family was left traumatized and the neighborhood lived in fear of similar operations (Bilal Kuchay, NPR, 2025).

Murran village in Pulwama also witnessed demolition. The house of Ahsan Ul Haq Sheikh was razed during a nighttime operation. The explosion caused damage to surrounding houses and terrified neighbors. Local Member of Parliament, Ruhullah Mehdi, confirmed that villagers consistently reported such demolitions were conducted by Indian authorities, though officials rarely acknowledge responsibility (Bilal Kuchay, NPR, 2025). The policy has spread to other districts as well. On 14 November 2025, ancestral property of Hurriyat leader Mohammad Yaqoob Sheikh in Pulwama was seized and demolished. On the same day, Mian Qayoom’s property in Srinagar was also destroyed under administrative orders (Monitoring Desk, 2025). In Udhampur, the home of a civilian resident was attached and demolished on 26 November 2025. The demolition strategy is applied broadly, targeting residential, commercial and religious properties, often justified under vague “security” claims.

The bulldozer policy is not limited to Pulwama or Srinagar. It has affected Kashmir Valley towns like HMT and Hyderpora. Past years’ cases show a consistent pattern: homes, shops and offices linked to freedom-supporting families were sealed or destroyed and occupants were left with little recourse. These demolitions are increasingly framed as a tool of deterrence. Authorities often warn residents of the consequences of alleged political associations. This extends the scope of punishment from individuals to entire households. The social consequences of these demolitions are profound. Families lose homes, businesses and community spaces. Children lose access to safe spaces for study and women bear a disproportionate burden of vulnerability. Fear of harassment, arrest, or further demolitions restricts mobility and curtails education. Many women in IIOJK now avoid public spaces and educational

institutions due to the psychological terror caused by these operations (Kashmir Media Service, 2025).

The policy also serves to weaken political and social leadership. Lawyers, teachers, shopkeepers and community organizers are often targeted. By destroying property, authorities dismantle both the economic base and social influence of key community members. This strategy reinforces compliance and suppresses dissent without formal charges or convictions. The Pahalgam incident in April 2025 exemplifies how demolitions are used strategically. Homes of freedom fighters’ families were destroyed shortly after the event, including those with no verified involvement. The demolitions acted as a warning to other communities that resistance or dissent would carry severe consequences. It also normalized the use of force against civilians, turning homes into instruments of collective punishment rather than spaces of shelter and safety.

Overall, the bulldozer policy is systematic and well-documented. Between 2019 and 2025, dozens of properties were demolished across Pulwama, Srinagar, Kathua, Kulgam and Udhampur. Reports indicate that more than a hundred households were affected by demolition drives post-Pahalgam alone. The method is deliberately public: neighbors see the demolition, creating fear and demonstrating the state’s coercive power. The bulldozer and demolition policy in IIOJK is a tool of punitive governance. It is neither incidental nor strictly a counter- terrorist measure. It targets communities associated with freedom movements, punishes households collectively and instills long-term fear. Cases such as Adil Thoker, Asif Sheikh and Ahsan Ul Haq Sheikh illustrate the human cost of these operations.

Beyond immediate destruction, the policy undermines economic stability, social cohesion and the safety of women and children. Understanding these demolitions as deliberate strategies of control, rather than law enforcement, is essential to documenting human rights violations and advocating for accountability (OHCHR, 2019; Bilal Kuchay, NPR, 2025; Monitoring Desk, 2025).

KASHMIRIS BEARING THE BRUNT OF SO-CALLED DEVELOPMENT: DISPLACEMENT, ENVIRONMENTAL DEGRADATION AND LIVELIHOOD LOSS

In the name of economic growth and infrastructure development, the people of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) are being systematically displaced, dispossessed and silenced. Across districts from Bandipora and Kupwara to Budgam, Tosa Maidan and Reasi, the so-called “development projects” have turned into instruments of marginalization, harming livelihoods, cultural heritage and ecosystems. Communities that have coexisted with the environment for generations are facing ecological destruction, legal disenfranchisement and forced displacement, all under the guise of progress.

Road Projects: Broken Promises and Lost Livelihoods

Infrastructure projects, particularly road construction, are frequently presented as public welfare initiatives. In reality, they have become vehicles for dispossession and administrative neglect, leaving local populations struggling to survive. In Bandipora, residents sacrificed fertile apple orchards and land for NABARD-funded roads, yet construction has remained incomplete for over 1.5 years (Lone, 2025). For example, the PMGSY Halamatpora to Peer Baba Ziyarat Hasrat Sultan-e-Arifeen Binilipora road (1.5 km) is 80% incomplete, while the Ganie Mohalla Aloosa to Halamatpora road (3 km) is 60% unfinished. Despite these delays, locals have received no compensation for the orchards they lost, lands that represented not only livelihood but generational wealth.

The consequences are tangible and immediate. Poor roads disrupt school commutes, hinder access to healthcare and restrict market connectivity, directly undermining economic stability. Allocated funds, including Rs. 6.25 crore for Sheikh Muqam- Aloosa and Ganie Mohalla-Halamatpora roads (with Rs. 56.84 lakh for five-year maintenance) and Rs. 4.21 crore for PMGSY Halamatpora to Mohalla Daki Ketson (with Rs. 38.35 lakh for maintenance), have failed to translate into functional infrastructure. Detailed contracts, geo-tagging and maintenance clauses exist on paper but remain ineffective in practice. Further, satellite township projects along the Ring Road threaten both cultivable and horticultural lands, which sustain nearly two-thirds of J&K’s population, potentially leaving farmers landless and economically dependent. These developments illustrate an approach that prioritizes infrastructure over the welfare of people and ignores environmental and cultural costs.

Large-Scale Mining and Resource Exploitation

Communities along the Sukhnag River and Tosa Maidan have historically depended on small-scale sand, stone and timber extraction, practices that were both sustainable and integral to local livelihoods. Post-2019, however, state-sanctioned mechanized mining operations by corporate contractors have monopolized these resources, criminalizing traditional labor (EPG, 2025). Tractor owners and laborers who once transported river sand and boulders for an honest living are now forced to purchase the same materials at inflated rates. Mechanized extraction disrupts river ecosystems, damages fish habitats and reduces water quality, undermining centuries of sustainable practices. Legal instruments such as Public Interest Litigations (PILs) and National Green Tribunal (NGT) bans, intended to protect the environment, have often been weaponized against indigenous practices, while corporate actors continue unchallenged.

This directly violates the Forest Rights Act (2006), which guarantees Community Forest Rights and Gram Sabha authority over local natural resources, further disempowering communities. The experience of Tosa Maidan demonstrates both the potential of community-led initiatives and the consequences of legal harassment. The Tosa Maidan Bachav Front (TBF) successfully reclaimed the meadow from military and corporate exploitation, establishing eco-tourism ventures, cultural festivals and sustainable jobs. However, litigation alleging timber smuggling disrupted these grassroots initiatives, whereas corporate tourism enterprises continued unchecked, highlighting a structural bias favoring profit over local welfare (Mohiuddin, 2025).

Lithium Mining in Salal: Displacement Under National Green Energy Goals

The discovery of 5.9 million tonnes of lithium in Salal, Reasi in February 2023 underscores how green energy projects can threaten local communities. Approximately 330 families face imminent displacement, with insufficient rehabilitation planning or consultation (Upadhyay, 2023). Residents emphasize that displacement is not merely economic, it represents an existential threat to ancestral lands, forests and mountains central to their identity and survival. Historical precedent from the Salal Dam construction shows that compensation was inadequate and quickly exhausted, eroding generational wealth and stability. Environmental risks compound the human cost. Open-cast mining threatens seismic stability in this high-risk Zone 5 region, with explosive operations potentially triggering earthquakes by creating fissures in rock strata, a scenario documented in Basel, Switzerland and Alice Springs, Australia (Dutta, 2023). Crucial Environmental and Social Impact Assessments (EIA/SIA) remain absent or inaccessible, leaving communities uninformed about the full scope of risks.

The social and psychological trauma of displacement is profound. Villagers, including Vimla Devi (58) and elderly women reliant on forests for firewood, articulate the loss of daily practices, cultural bonds and intergenerational continuity. As one resident noted, uprooting the community would erase not only homes but also the very identity and livelihood systems that sustain life in Salal (Upadhyay, 2023). Srinagar-Pahalgam Road Project: Environmental and Livelihood Costs The proposed Srinagar-Pahalgam road, connecting Khrew, Pastuna and Tral, further exemplifies the ecological recklessness of so-called development.

The project requires cutting down 845 trees and acquiring 108 kanals (~13.5 acres) of forest land (EPG, 2025). The route passes through the Tral Wildlife Sanctuary, threatening biodiversity, wildlife habitats and exacerbating 23September – December 2025human-wildlife conflict. Tunneling operations raise geological and water source risks in a seismic zone 5 region, potentially endangering surrounding communities.

Local livelihoods are directly at risk. Khrew, already suffering from cement dust pollution, faces worsening air quality and health hazards. Saffron cultivation, a critical economic and cultural activity, is threatened by deforestation and dust. Orchardists in Rafiabad fear the destruction of generational apple orchards, representing both economic survival and cultural heritage. Public health consequences, including rising incidences of asthma, bronchitis, cardiac issues and other chronic illnesses, have already been documented (Showkat, 2025). Despite legal requirements under the Forest Conservation Act (1980), Wildlife Protection Act (1972) and Environment Protection Act (1986), authorities have advanced construction with minimal EIA or public consultation, risking judicial challenges and violating Article 21 of the Constitution.

Patterns of Systemic Neglect and Exploitation

Across J&K, a disturbing pattern emerges. Communities consistently sacrifice land, orchards and livelihoods in the name of development, yet projects are delayed, incomplete, or environmentally destructive. Legal and administrative frameworks, including litigation, NGT orders and corporate monopolization, tend to favor wealth and influence over the needs of local populations. Consultation, consent and transparency are frequently ignored, violating statutory and customary rights. The human toll is staggering: loss of income, displacement, health hazards, environmental degradation and erosion of cultural heritage are now common consequences of infrastructure and resource projects in Kashmir. Economic growth cannot justify dispossession, environmental destruction and the erasure of cultural identity.

Development that ignores community consent, environmental safeguards and social justice is exploitative, unsustainable and morally indefensible. Existing infrastructure often suffices; duplicating roads and building extractive projects unnecessarily destroys forests, orchards, rivers and ecosystems. Legal frameworks such as the Forest Rights Act, environmental laws and judicial precedents are routinely bypassed or misused to legitimize corporate exploitation. Green energy projects, such as lithium mining, cannot proceed at the cost of displacement and cultural annihilation. Kashmiris continue to bear the ultimate price for “progress” that is often ill-conceived and top-down in nature.

Calls for Reform and Sustainable Alternatives

To mitigate these impacts, development in Kashmir must be inclusive, participatory and environmentally sustainable. Communities should be central to decision-making processes, with Gram Sabhas approving projects affecting their lands. Transparent compensation and rehabilitation must be guaranteed before any displacement occurs.

Sustainable alternatives include:

◊ Improving existing roads rather than building new, ecologically destructive routes.

◊ Promoting small-scale, community-driven eco-tourism, agriculture and mining.

◊ Conducting comprehensive EIA and socio-economic impact assessments, with public disclosure.

◊ Enforcing FRA provisions and equitable access to natural resources.