Enforced Disappearances and India's Inaction in IoK

Enforced Disappearances and India's Inaction in IoK

Abstract

This paper explores the ongoing crisis of enforced disappearances in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir (IoK), examining the scale and systemic nature of these human rights violations. Despite widespread documentation, enforced disappearances remain largely unaddressed by the Indian government and international bodies. Drawing on a human rights framework and the theoretical lens of liberal institutionalism, the study critiques the failure of international institutions to hold India accountable. The research combines qualitative interviews with survivors and human rights activists, alongside secondary data from organizations such as the IPTK and APDP. The paper highlight the emotional and societal toll on families, particularly women, including widows and "half-widows," and the presence of unmarked graves as symbols of erasure. The study argues that enforced disappearances in IoK reflect a broader human security crisis, demanding urgent legal and institutional reform within international human rights frameworks.

Keywords: Enforced disappearances, human rights, liberal institutionalism, Jammu and Kashmir, unmarked graves.

Enforced Disappearances and India's Inaction in Jammu & Kashmir

Enforced disappearances (EID) have become one of the most devastating and controversial human rights violations in Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IoK), where they have been a central feature of the conflict that has raged since the partition of British India in 1947. The region’s unresolved political status has fuelled decades of tension, with the central issue revolving around the question of Kashmir's right to self-determination. Jammu and Kashmir, a princely state at the time of the partition, was given the choice to accede either to India or Pakistan. However, the decision made by the then-Maharaja Hari Singh to join India, without the consent of the Kashmiri people, sparked immediate and lasting conflict, as the majority Muslim population of Kashmir believed they should align with Pakistan. This dispute has not only caused military confrontations but has also led to persistent uprisings in Kashmir, where Kashmiri Muslims have demanded either greater autonomy or complete independence from Indian rule. In the late 1980s, following a long period of political unrest and frustrations over the region’s governance, the resistance movement for Kashmiri self-determination grew in intensity. The Indian government, aiming to suppress this rising freedom struggle, responded by deploying a large military presence and justifying its actions as necessary to counter what it labelled as insurgency and separatism. In the process, India resorted to a range of brutal counterinsurgency tactics, including mass arrests, torture, extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances, with devastating consequences for the civilian population.

The use of enforced disappearances emerged as a particularly pervasive and chilling method to break the spirit of resistance and quash calls for independence. Enforced disappearances are one of the most egregious violations of human rights, as they not only strip individuals of their liberty but also deny them any legal protection or acknowledgment, placing them outside the bounds of justice. Defined by the UN, this crime occurs when individuals are arrested, detained, or abducted by government authorities or organized groups, with their fate concealed and their whereabouts undisclosed.

The impact is devastating, depriving victims of their right to a fair trial, the right to life and basic human dignity, while leaving their families in torment and uncertainty. In 2010, the UN General Assembly, in resolution 65/209, expressed profound concern about the rising prevalence of enforced disappearances globally and designated 30 August as the International Day of them Victims of Enforced Disappearances, starting in 2011, to raise awareness and seek justice.1 Despite the global consensus on the need to address this crisis in Indian occupied Jammu & Kashmir, India, while signing the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED)2 in 2007, has yet to ratify the treaty or pass domestic laws to criminalize enforced disappearances. During the third Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of India in May 2017, the Indian government rejected all eight recommendations urging the ratification of the ICPPED, highlighting a lack of commitment to addressing the issue.3

Additionally, the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (WGEID) made formal requests to visit India in 2010 and 2018 to investigate ongoing cases, but as of 2018, the Indian government failed to respond positively.4 This persistent lack of accountability and unwillingness to implement international legal standards has allowed human rights violations to persist unabated, particularly in regions like Jammu and Kashmir, where enforced disappearances remain widespread. The failure to take meaningful action not only perpetuates the suffering of victims and their families but also undermines India's obligations under international human rights law.

The international community must hold India accountable for this grave issue, pressing for urgent reforms and justice for the victims of enforced disappearances. The Indian state has justified its use of such repressive measures as a means to restore order and suppress terrorism, but the widespread nature of these violations reflects a pattern of colonial-style repression that undermines the basic rights and freedoms of the Kashmiri people. The trauma inflicted by the uncertainty surrounding the fate of loved ones has left families devastated, with many unable to mourn properly or seek legal redress.

The use of enforced disappearances has also had a lasting impact on the broader Kashmiri society, leading to a sense of fear, suspicion and social fragmentation. While the international community has condemned these actions, no substantial measures have been taken to hold the perpetrators accountable, leaving the people of Kashmir to endure a cycle of suffering with little recourse for justice. Thus, the practice of enforced disappearances remains an enduring symbol of the brutal and unresolved nature of the Kashmir conflict, highlighting the human cost of a geopolitical dispute that shows no signs of resolution.

Methodology:

This study adopts a secondary qualitative research approach, relying on existing literature, reports and case studies to investigate enforced disappearances in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir (IoK). The research analyzes reports from international human rights organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and local NGOs such as the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) and the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS). It also examines legal documents, government reports and academic articles to explore the scale, patterns and impacts of enforced disappearances.

This study uses a human rights-based approach, with a focus on the theoretical framework of liberal institutionalism, to critically assess the role of both national and international institutions in failing to prevent or address these human rights violations. By synthesizing and analyzing secondary data, the research seeks to highlight the ongoing human security crisis and its social, political and emotional consequences for affected families.

Scale and Impact: The Continuing Reality of Enforced Disappearances

Human rights organizations, including the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), estimate that between 8,000 and 10,000 individuals have been forcibly disappeared in Jammu and Kashmir since the early 1990s,5 with the vast majority of these cases occurring during military crackdowns and operations. In 2011, an investigation uncovered over 2,700 unmarked graves across four districts in north Kashmir.6 Although local police claim these graves contain the bodies of "unidentified militants," the report compellingly reveals that 574 of the bodies were identified as those of local civilians who had been forcibly disappeared. Seventeen of these bodies were exhumed and reburied by their families, offering a painful confirmation of their fate.

This tragic evidence, along with the large number of unmarked graves, serves as undeniable proof of mass killings carried out under state authority. Whilethese findings are deeply disturbing, they represent only a fraction of the true extent of the crisis, as many disappearances remain unreported and unaccounted for. The victims include men, women and children who were often detained during siege and search operations, where entire villages were targeted and individuals were arbitrarily rounded up based on suspicion of supporting insurgent activities. This systemic and brutal repression underscores the devastating human toll of the ongoing conflict in the region.

These disappearances have taken place primarily in rural and border areas, where resistance to Indian rule is often most intense. The forced disappearances usually follow a pattern: individuals are detained in illegal crackdowns, tortured and executed. Many victims are never seen again, leaving their families to endure a long period of uncertainty about their loved ones' fate. While some bodies have been found in unmarked graves, the Indian government has continued to deny the scale of these violations, attributing the disappearances to militants fleeing across the border into Pakistan.

International human rights law has long condemned such practices, framing enforced disappearances as violations of fundamental human rights, including the right to life and the prohibition on torture. Despite ample documentation from organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and the APDP, the Indian government’s refusal to engage meaningfully with these reports has allowed the cycle of impunity to persist. The inability of the international community to challenge India’s actions in Kashmir further perpetuates this tragic situation. The lack of independent international investigations into the disappearances reflects the limitations of existing human rights frameworks and the geopolitical realities that often prevent meaningful action.

The Paradox of Liberal Institutionalism

The response of the international community to the issue of enforced disappearances in Jammu and Kashmir has been tepid at best, despite the widespread recognition of these abuses. The Kashmir conflict itself is a highly contentious issue in international relations, as it involves two nuclear-armed countries, India and Pakistan, whose respective territorial claims have made it a focal point of both regional and international diplomacy. The international community, especially key global powers, has largely avoided taking strong action against India due to strategic considerations, including India’s growing influence in global politics and its position as a counterbalance to China.

Liberal institutionalism offers a compelling lens for understanding the potential and limitations of international institutions in addressing human rights violations, such as enforced disappearances in Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IOK). The theory emphasizes the role of international organizations in promoting norms, fostering cooperation and addressing collective challenges, including conflict resolution and the protection of human rights. However, the application of liberal institutionalism to the crisis in IOK reveals a significant paradox: while multilateral frameworks aim to build consensus and promote accountability, they are often constrained by the voluntary nature of state compliance and the absence of robust enforcement mechanisms.

In theory, institutions like the United Nations are well-positioned to address the systematic human rights abuses in IOK, including enforced disappearances. The UN has adopted resolutions emphasizing the right to self-determination for Kashmiris and established mechanisms to monitor and address such atrocities. However, in practice, these mechanisms remain largely ineffective due to the lack of cooperation from India, a powerful member state that maintains the issue is a domestic matter. This reflects a core limitation of liberal institutionalism: while international institutions provide a platform for norm-setting and mediation, their success depends on the willingness of states to adhere to and implement these norms. India’s refusal to ratify the ICPPED and its rejection of recommendations during the UPR process underscore this challenge.

Despite global condemnation of enforced isappearances in IOK, India has used its geopolitical leverage to evade accountability. These dynamic highlights a critical weakness in liberal institutionalism’s reliance on voluntary compliance, as powerful states can obstruct multilateral efforts, rendering institutions ineffective in addressing gross human rights violations. The failure of international institutions in IOK also exposes the broader tension between state sovereignty and the enforcement of international norms. While liberal institutionalism champions the idea of shared governance and collective responsibility, it struggles to reconcile this with the entrenched principles of sovereignty that dominate the international system. India’s strategic importance as an emerging global power further complicates the situation, as many states are reluctant to challenge its actions in Kashmir for fear of jeopardizing bilateral relations or economic interests. This underscores the realist critique of liberal institutionalism, which argues that power dynamics and national interests often trump normative commitments.

Nonetheless, the importance of multilateralism and norm-building cannot be dismissed. Institutions like the United Nations, despite their shortcomings, play a vital role in keeping human rights violations in the global spotlight, fostering dialogue and providing a framework for future accountability. The adoption of global conventions, even when not universally ratified, helps establish benchmarks for acceptable state behavior and empowers civil society organizations to demand justice. In the context of IOK, multilateral efforts have amplified the voices of victims and human rights advocates, creating pressure for reform and accountability. The liberal institutionalism highlights both the potential and the limitations of international institutions in addressing enforced disappearances in IOK. While these bodies are essential for promoting multilateral cooperation and building norms, their effectiveness is undermined by the lack of binding enforcement powers and the dominance of state-centric interests. Addressing these challenges requires strengthening international mechanisms, ensuring greater accountability for powerful states and fostering a more inclusive and equitable multilateral framework that prioritizes human rights over political expediency.

Unmarked Graves and the Human Security Crisis in IoK

Since the early 2000s, the discovery of unmarked graves in IoK has raised serious concerns about the extent of enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings carried out by Indian occupation forces. A report by the Jammu and Kashmir State Human Rights Commission identified 2,730 bodies in unmarked graves across four districts.7 The International People's Tribunal on Human Rights and Justice reported over 6,000 unmarked and mass graves in the region.8 These graves are concentrated in remote areas, particularly in Baramulla and Uri, where military operations have been most intense. In 2005, the APDP uncovered evidence of at least 940 unmarked graves in Baramulla,9 many believed to contain the remains of missing Kashmiris. Indian authorities often labelled these graves as those of "foreign militants," but local residents insist they hold the bodies of civilians, victims of military detentions and executions.

Witness testimonies have described disturbing practices by occupation forces, such as throwing bodies into the River Jhelum or burying them in secret locations. Despite these reports, the Indian government has maintained that the graves contain the remains of insurgents, resisting independent forensic investigations and downplaying the international legal implications of these acts. The reluctance to investigate and the refusal to allow external scrutiny have prompted widespread scepticism, with many believing that these graves conceal the bodies of innocent Kashmiris. Mass graves in Jammu and Kashmir, particularly in Baramulla, Kupwara and Bandipora, offer grim evidence of state-led extrajudicial executions. Investigations by the International Peoples' Tribunal on Kashmir (IPTK) and APDP have revealed over 2,700 graves, containing more than

2,900 bodies, scattered across 55 villages. A staggering 87.9% of these graves remain unnamed,deepening the uncertainty surrounding the victims' identities.

• Baramulla: 1,122 graves with 1,321 bodies, 90.3% unnamed.

• Kupwara: 1,453 graves with 1,487 bodies, 87.9% unnamed.

• Bandipora: 125 graves with 135 bodies, 65.6% unnamed.10

These findings suggest that many of the victims were executed under circumstances violating international human rights standards. The discovery of mass graves holding multiple bodies further indicates that the killings were systematic, not isolated incidents. A disturbing strategy employed by Indian occupation forces in Jammu and Kashmir involves "false encounters," where civilians are killed and falsely portrayed as militants to justify extrajudicial killings. One of the most prominent cases is that of Ali Mohammad Padder, a government employee who was abducted, killed and later presented as a militant in a staged encounter. His exhumed body confirmed the falsification, exposing the state's role in concealing the truth behind such killings.

In addition, local gravediggers, often coerced by the authorities, were made complicit by burying the bodies in unmarked graves, further aiding in the concealment of these unlawful acts. Many of these graves were dug on sacred or community land, intensifying the emotional trauma for local residents who witnessed the desecration of their cultural spaces. The gravediggers themselves suffered from significant psychological distress, carrying long-term emotional scars from their forced involvement in these practices, highlighting the far-reaching consequences of state-sanctioned violence and its impact on both the victims and the local population.

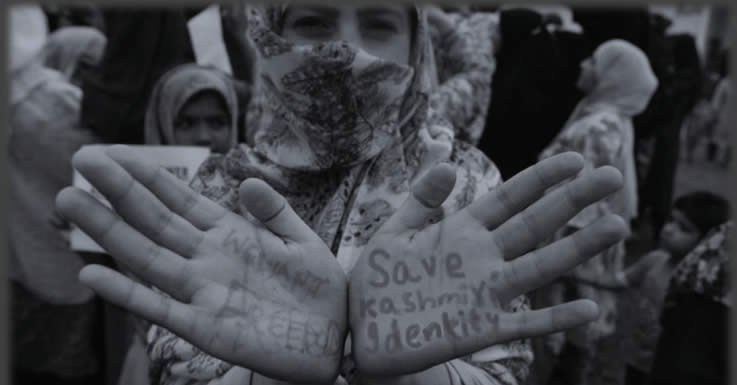

Widows & Half Widows

Enforced disappearances in Jammu and Kashmir have led to a unique form of suffering for women, referred to as "half-widows." These women, whose husbands have been abducted, are left in a state of perpetual uncertainty, with nearly 3,000 living under these traumatic circumstances.11 Since 1989, the conflict has resulted in 22,980 widowed women and 107,974 orphaned children. These women are trapped in limbo, unable to mourn or legally declare their husbands as deceased. In a region where traditional gender norms position men as the primary breadwinners, the disappearance of a husband results in immediate financial instability.

The loss of income, coupled with the lack of state support or compensation, forces many half widows into extreme poverty. Without closure or an official recognition of their husbands’ deaths, these women face social isolation, unable to remarry or move on. The community stigmatizes them, seeing them as symbols of unresolved tragedy. This ambiguity traps them in a cycle of psychological distress, social marginalization and financial hardship. The suffering of half widows and orphans is part of the broader gendered violence that permeates the conflict in Jammu and Kashmir. Women, already marginalized by traditional gender roles, bear the disproportionate brunt of the conflict’s violence, both in terms of physical abuse and psychological trauma.

The cases of sexual violence, such as the Kunan Poshpora mass rape and the Shopian case, are a testament to the systemic use of gendered violence by state forces.12 These crimes reflect the broader culture of impunity, where sexual violence is often dismissed or ignored, leaving women and families without justice or closure. The violence also affects women’s ability to contribute to their families and communities. With the loss of family members to enforced disappearances or violence, many women are forced to take on roles they are unprepared for, such as financial providers or community leaders. The psychological trauma that comes with these responsibilities, compounded by the lack of social support, further exacerbates the gendered impacts of the conflict.

Children of the Disappeared

The impact of enforced disappearances extends beyond women to children, particularly those who lose their fathers. Approximately 50% of the forcibly disappeared are young men, many of whom are fathers or primary caretakers. This leaves children without emotional and financial support, fostering a sense of abandonment and fear. The psychological toll on children is severe, with many experiencing PTSD, anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts. Witnessing the abduction of a parent or living in uncertainty about their fate exacerbates the emotional trauma.

The absence of closure prevents children from properly grieving their losses, leaving them in a state of social limbo. These children often face stigma and discrimination, as families of the disappeared are treated with suspicion. This social exclusion, combined with the ongoing trauma, severely impacts their mental health and development. The loss of a father or male caretaker often disrupts children’s education. With the primary breadwinner gone, many children are forced to abandon school to support their families. The absence of male family members not only compromises the household's economic stability but also limits children’s opportunities for education, further entrenching the cycle of poverty and marginalization. In IoK, where school closures due to curfews and military operations are common, children face additional barriers to education. This disruption leads to widening literacy gaps between boys and girls, exacerbating gender inequality and limiting the future prospects of these children.

Psychological Impact

The enforced disappearances and mass graves have a profound psychological impact on local communities, deeply affecting the families of the disappeared and the broader population. The psychological toll on half widows is profound. Deprived of the ability to grieve, they live with an unresolved sense of loss. The trauma of not knowing whether their husbands are alive or dead exacerbates these conditions, leaving these women in a constant state of uncertainty. Furthermore, half widows are often distanced from their husband’s families due to the stigma surrounding enforced disappearances, deepening their isolation. Mass graves, often situated close to homes, schools and places of worship, perpetuate an atmosphere of fear, uncertainty and trauma.

Families of the disappeared endure chronic anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) due to the uncertainty surrounding the fate of their loved ones. The inability to mourn or achieve closure exacerbates their emotional turmoil. A study highlighted that 99.7% of young adults in Kashmir felt the presence of violence, with 95.4% experiencing psychological distress.13 This uncertainty is compounded by the suppression of truth by the Indian government, which has consistently blocked independent investigations into the atrocities, leaving families in a state of social and emotional isolation.

The proximity of mass graves to vital community spaces intensifies the trauma, with the desecration of sacred lands further adding to the emotional burden. The pervasive fear of being targeted by occupation forces for demanding justice creates a toxic social environment, hindering public mourning and the pursuit of accountability. In this context, mass graves have become more than just physical sites of violence; they symbolize the state's deliberate attempt to erase dissent and suppress the collective memory of the Kashmiri people, exacerbating the psychological scars inflicted by enforced disappearances.

Conclusion

Enforced disappearances in IoK are both a humanitarian crisis and a significant threat to regional human security. These violations not only strip individuals of their basic rights, such 13 International Committee of the Red Cross, Psychological Impact of Conflict on Children and Young Adults in as life, liberty and protection from torture, but also create widespread fear and psychological trauma for families and communities. Beyond the immediate humanitarian impact, enforced disappearances undermine broader human security by destabilizing the region, eroding the rule of law and fostering an environment of distrust and violence. This pervasive insecurity prevents the establishment of lasting peace, as individual rights are subordinated to political and military agendas, further fueling instability and conflict in the region.

Bibliography:

Amnesty International. "India: Need for Urgent Action as Police Report Confirms Existence

of Mass Graves in Kashmir." July 2011. https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-

content/uploads/2021/07/asa200432011en.pdf.

Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), Kashmir: The Impact of Enforced

Disappearances on Families, 2020, https://www.apdpkashmir.org.

Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP). Report on Unmarked Graves in

Baramulla. 2005. Accessed January 9, 2025. https://apdpkashmir.com.

International People's Tribunal on Kashmir (IPTK) and Association of Parents of

Disappeared Persons (APDP). Report on Mass Graves in Jammu and Kashmir. 2009.

https://www.iptk.org.

International Committee of the Red Cross, Psychological Impact of Conflict on Children and

Young Adults in Kashmir, 2018, https://www.icrc.org.

Jammu and Kashmir State Human Rights Commission. Report on Unmarked Graves.

Accessed January 7, 2025. https://www.jkshrc.in.

J&K State Human Rights Commission, Impact of the Conflict on Families of the

Disappeared in Kashmir, 2019, https://www.jkshrc.org.

United Nations General Assembly. A/RES/65/209 - International Day of the Victims of

Enforced Disappearances. New York: United Nations, December 21, 2010.

https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/701284?ln=en.

United Nations Treaty Collection. International Convention for the Protection of All Persons

from Enforced Disappearance. Accessed January 9, 2025.

https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-

16&chapter=4&lang=en.

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Ratification Status for

India. Accessed January 8, 2025.

https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-

16&chapter=4&lang=en.

Related Reports