International concerns HRC56

International concerns HRC56

INTRODUCTION

The following document presents a comprehensive compilation of international reactions to the issue of human rights violations in Indian occupied Jammu and Kashmir, spanning the period from January 2024 to April 2024. This report aims to provide a consolidated overview of the statements made by prominent personalities and organizations, as well as the extensive coverage provided by leading newspapers and magazines, concerning the grave situation unfolding in this disputed region.

The conflict in Indian occupied Jammu and Kashmir has long been a matter of international concern, stemming from the aspirations of the Kashmiri people for self-determination. Throughout the years, numerous reports and testimonies have shed light on the violation of fundamental human rights and the immense suffering endured by the Kashmiri people. This report endeavours to bring together the voices of influential individuals and organizations that have expressed their concerns regarding the human rights situation in Indian occupied Jammu and Kashmir. It incorporates coverage of international the media outlets including prominent newspapers and magazines, offering a comprehensive overview of the prevailing discourse surrounding the ongoing crisis.

By compiling these international reactions and media coverage into a single document, we seek to underscore the urgent need for international attention and action in addressing the human rights abuses occurring in Indian occupied Jammu and Kashmir. Through highlighting the perspectives of those who have spoken out against these violations, we aim to emphasize the pressing nature of the situation and advocate for the resolution of the Kashmir issue in a manner that upholds the rights and aspirations of the Kashmiri people. It is our sincere hope that this report will contribute to raising awareness about the challenges faced by the Kashmiri people and foster informed discussions among stakeholders and decision- makers. By comprehending the gravity of the human rights situation, we can collectively work towards promoting peace, justice, and the realization of the legitimate right to self-determinationfor the people of Indian occupied Jammu and Kashmir.

We encourage readers to thoroughly review the findings of this report, engage in constructive dialogue, and explore opportunities to support initiatives aimed at finding a just and lasting resolution to the Kashmir conflict. Together, we can strive for a future where human rights are upheld, and the aspirations of all communities in Indian occupied Jammu and Kashmir are respected. Please note that this report represents a compilation of various sources and does not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of any specific individual or organization.

INDIA: UN EXPERTS URGE CORRECTIVE ACTION TO PROTECT HUMAN RIGHTS AND END ATTACKS AGAINST MINORITIES IN LEAD UP TO ELECTIONS

GENEVA (7 March 2024) – UN human rights experts* today sounded the alarm over reports of attacks on minorities, media and civil society in India and called for urgent corrective action as the country prepares to hold elections in early 2024. “We are alarmed by continuing reports of attacks on religious, racial and ethnic minorities, on women and girls on intersecting grounds, and on civil society, including human rights defenders and the media,” the UN experts said, expressing concern that the situation is likely to worsen in the coming months ahead of national elections.

They noted reports of violence and hate crimes against minorities; dehumanising rhetoric and incitement to discrimination and violence; targeted and arbitrary killings; acts of violence carried out by vigilante groups; targeted demolitions of homes of minorities; enforced disappearances; the intimidation, harassment and arbitrary and prolonged detention of human rights defenders and journalists; arbitrary displacement due to development mega-projects; and intercommunal violence, as well as the misuse of official agencies against perceived political opponents.

“We call on India to implement its human rights obligations fully and set a positive example by reversing the erosion of human rights and addressing recurring concerns raised by UN human rights mechanisms,” the experts said. They deplored the low level of response from India to their communications, noting that of the 78 communications sent by UN human rights experts over the past five years, from 7 March 2019 to 6 March 2024, only 18 received replies from the Government that could be made public. During the reporting period between 1980 and 12 May 2023, 445 cases referred to India by the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (WGEID) under its humanitarian procedure remained pending, with the fate and whereabouts of the alleged victims unknown (A/HRC/54/22).

The experts also regretted that despite India’s standing invitation to UN Special Procedures since 2011, there have been no country visits since 2017, with 15 active pending requests by UN human rights experts to which there is no reply from the Government on their permission to conduct official visits to the country. They urged India to take concrete measures to address concerns raised in their previous communications and reports. The experts called on the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to continue to monitor the evolving human rights situation in India, and for the Human Rights Council to consider measures that could contribute to the prevention of human rights violations in the country, in line with its mandate under General Assembly resolution 60/251.

“In light of continuing reports of violence and attacks against religious, racial and ethnic minorities, and other grave human rights issues, and the apparent lack of response by authorities to concerns raised, we are compelled to express our grave concern, especially given the need for a conducive atmosphere for free and fair elections in accordance with the early warning aspect of our mandates,” they said. *The experts: Reem Alsalem, Special Rapporteur on violence against women and girls, its causes and consequences; Dorothy Estrada Tanck (Chair), Claudia Flores, Ivana Krstić, Haina Lu, and Laura Nyirinkindi, Working group on discrimination against women and girls;

Mary Lawlor, Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders; Priya Gopalan (Chair- Rapporteur), Matthew Gillett (Vice-Chair on Communications), Miriam Estrada-Castillo, Mumba Malila, Working Group on Arbitrary Detention; Nazila Ghanea, Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief; Clément Nyaletsossi Voule, Special Rapporteur on freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; Ashwini K.P., Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance; Aua Baldé (Chair- Rapporteur), Gabriella Citroni (Vice-Chair), Angkhana Neelapaijit, Grażyna Baranowska, and Ana Lorena Delgadillo Perez, Working Group on enforced or involuntary disappearances; Nicolas Levrat, Special Rapporteur on minority issues; Cecilia M. Bailliet, Independent

Expert on human rights and international solidarity; Paula Gaviria Betancur, Special Rapporteur on the human rights of internally displaced persons; Irene Khan, Special Rapporteur on the right to freedom of opinion and expression; Ben Saul, Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism; Alice Jill Edwards, Special Rapporteur on Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; Balakrishnan Rajagopal, Special Rapporteur on the right to housing.

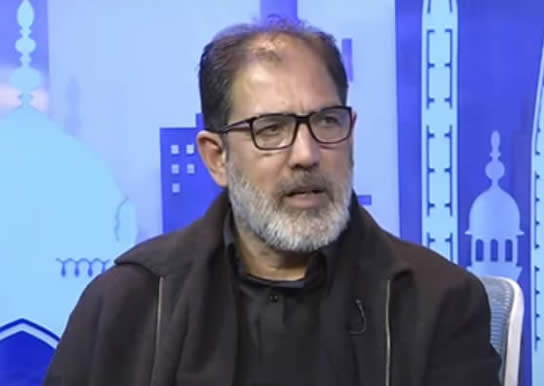

IMMEDIATELY RELEASE IRFAN MEHRAJ– A CALL FROM CIVIL SOCIETY ON THE FIRST ANNIVERSARY OF HIS CONTINUING ARBITRARY DETENTION

(20 March 2024) We, the undersigned civil society organisations, call for the immediate and unconditional release of Kashmiri journalist and human rights defender Irfan Mehraj. While on a professional assignment on 20 March 2023, Mehraj was summoned for questioning and arbitrarily detained by India’s National Investigation Agency (NIA) in Srinagar under provisions of the Indian Penal Codeand the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act.

Mehraj is a well-regarded Srinagar-based independent journalist. He is the founding editor of Wande Magazine and a senior editor at TwoCircles.net. He was a frequent contributor to leading news publications in Kashmir, India and internationally (including Deutsche Welle and TRT World). Mehraj also previously worked as a researcher at the Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS), an internationally recognized leading civil society organisation in Indianadministered Kashmir that has done ground-breaking and extensive human rights documentation work inthe region.

Mehraj is facing multiple politically motivated charges including ‘sedition’ and ‘funding terror activities’ along with internationally renowned human rights defender Khurram Parvez,1 the Program Coordinator for JKCCS. Parvez has been arbitrarily detained for over,two and a half years. The NIA targeted Mehraj for being ‘a close associate of Khurram Parvez.’ Both Mehraj and Parvez are presently in pre-trial detention in the maximum-security Rohini prison in New Delhi, India. In June 2023, United Nations experts expressed serious concerns regarding the charges against and arrest of Mehraj and Parvez, stating that their continued detention is ‘designed to delegitimize their human rights work and obstruct monitoring of the human rights situation in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir.’

On 7 March 2024, UN experts sounded the alarm on the “harassment and prolonged detention of human rights defenders and journalists” in the country. The cases against Mehraj and Parvez seek to criminalize human rights work in Indian administered Kashmir and the support for any such work under the guise of countering financing of ‘terrorism. The UAPA is a counter-terrorism law often used against human rights defenders by the Indian authorities to target, harass, intimidate, and detain them on bogus and politically motivated charges.

In May 2020, UN experts expressed concerns over the non-conformity of various UAPA provisions with international human rights standards. In October 2023, they reiterated their concerns, stating that the pre- trial detention period of 180 days–which can subsequently be increased–is beyond reasonable. They called for a review of the UAPA in line with international human rights standards and with recommendations made by the Financial Action Task Force. Irfan Mehraj’s detention is part of a growing crackdown against journalists and human rights defenders in Indian-administered Kashmir.

Since August 2019, when Jammu and Kashmir’s special status was arbitrarily revoked, there has been increasing harassment against the media. Journalists have been arrested, media outlets shut down, and self-censorship has become pervasive. In another emblematic case, on 29 February 2024, journalist Asif Sultan was re-arrested by the Jammu and Kashmir police shortly after being released and having spent five years in detention under the UAPA and the Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act. Kashmiri journalists also face travel bans and revocation of their passports by Indian authorities. Consequently, information flow from Kashmir– especiallyon human rights violations–has been severely restricted.

Mehraj’s continuing arbitrary detention is emblematic of the Indian authorities’ escalating crackdown on human rights including the rights to freedom of expression and association in Indian-administered Kashmir. The detention of Mehraj and Parvez creates a chilling effect among other human rights defenders and journalists, thereby allowing grave and systemic human rights violations to continue with impunity and minimal transparency. Our organisations, therefore, call for the immediate release of Irfan Mehraj and Khurram Parvez and for an end to all reprisals against Kashmiri human rights defenders and journalists. We urge Indian authorities to repeal or amend the UAPA and to bring it in conformity with international human rights standards, and to end the criminalisation of human rights defenders, journalists, and their invaluable work.

We also call upon Indian authorities to comply with their international human rights obligations by respecting, protecting, promoting, and fulfilling the human rights of everyone as well as byallowing civil society and the media to freely operate in Indian-administered Kashmir and India. In addition, the authorities must cease their longstanding targeting, harassment, and forced closure of international civil society. Likewise, the authorities must refrain from attacking intergovernmental organisations, including UN Special Rapporteurs and other human mechanisms. These entities should have unfettered access to Indian-administered Kashmir and Kashmiri detainees Signed by: Amnesty International Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA) Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances (AFAD) CIVICUS: World Alliance for Citizen Participation Front Line Defenders FIDH (International Federation for Human Rights), within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders Human Rights Watch International Service for Human Rights (ISHR) Kashmir Law and Justice Project.

RE: REVIEW OF THE ACCREDITATION STATUS OF THE NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION OF INDIA

Dear Chairperson,We, the undersigned, are writing to bring to your attention serious concerns regarding the National Human Rights Commission of India (NHRCI) ahead of the fifth review of its accreditation status by the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI) Sub- Committee on Accreditation (SCA).

On 9 March 2023, several signatories to this letter had written to your office sharing their concerns about the functioning of the NHRCI.1 Taking cognizance of the letter and other civil society submissions, in March, GANHRI-SCA deferred the NHRCI’s re-accreditation by 12 months after considering the NHRCI’s failure to effectively discharge its mandates to respond to the escalating human rights violations in India, lack of pluralism in selection and appointments of its duty holders and insufficient cooperation with human rights bodies, amongst others.2 GANHRISCA also recommended the NHRCI to improve its processes and functions in line with the United Nations

Principles relating to the Status of National Institutions (The Paris Principles).3 However, both the NHRCI and Indian government have yet again failed to make the requisite improvements. The upcoming review comes shortly after the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Volker Türk, raised concerns about the increasing restrictions on the civic space and discrimination against minorities in India ahead of the country’s General Elections.4 These concerns were further underlined by various UN human rights experts who drew attention to “attacks on minorities, media and civil society” in the country.5 India has also constantly been downgraded on various development and human rights indices over the past few years.6 In light of this, we strongly urge GANHRI-SCA to amend the current ‘A’ rating of the NHRCI to accurately reflect its failure to comply with the Paris Principles and address the deteriorating human rights situation in India. We provide detailed reasons below.

Involvement of Police officers in NHRCI investigations

The Protection of Human Rights Act (PHRA),1993 empowers the Indian government to appoint police officers of the rank of Director General of Police or above as necessary for the efficient performance of the NHRCI.7 In the 2017 and 2023 reviews, the SCA had recommended the real or perceived conflict of interest in engaging police officers for the investigation of human rights violations, particularly those committed by the police.8 It had further noted that the Paris Principles require a national human rights institution to operate independent of government interference and recommended amendment of the PHRA in a manner that allows independent appointment of suitable and qualified persons for investigative positions.9

However, the Indian government has not undertaken any legislative process to fulfil the SCA’s recommendation to date nor has it initiated any consultation on the same. On the contrary, the NHRCI’s website boasts of “multi-dimensional” inquiries by the Investigation department, termed as “specialised”, but comprising solely of police officers.10 Consequently, according to the NHRCI’s most recent human rights cases statistics published on its website, a total of 469 cases of deaths in police custody and during police encounters remain pending.11 Furthermore, by its own admission, of all the cases in which the NHRCI recommended monetary relief in the month of February 2024, not a single case related to death in police custody.

12 In an emblematic case, in October 2022, the Gujarat police used batons to beat nine Muslim men after tying them to a pole for allegedly throwing stones at a Hindu festival celebration.13 While India’s Supreme Court criticized the Gujarat police and remanded the errant police officials to 14- days in custody14, the NHRCI did not take cognizance of the matter. In another long-standing case where 16 peaceful protesters were killed due to excessive use of force by the police in Thoothukudi town of Tamil Nadu, the NHRCI has repeatedly tried to undermine victims’ access to justice.

On 22 May 2018, the protesters were marching against the expansion of a copper smelter that was linked to water contamination, air pollution and other forms of environmental degradation when the police opened fire on them.15 In May 2018, eight UN special rapporteurs condemned the use of excessive force by the police in the case and called on the Indian government to carry out an independent and transparent investigation, without delay.16 While the NHRCI was quick to take cognizance of the matter, it disposed of it within five months based solely on the response of the Tamil Nadu government.17 The NHRCI did not make the report of the investigation public, nor did it provide a copy to the complainant. It was only after the intervention of the Tamil Nadu state’s High Court in 2021 that the NHRCI shared the report with the Court and the complainant in a sealed cover.18 Despite the Court’s order, the NHRCI has not reopened the case, nor has it indicted a single police officer for the killings.

Lack of Pluralism and Opacity in the Selection Criteria

The SCA has repeatedly raised concerns about the lack of diversity in the NHRCI and recommended a “pluralistic balance in its composition and staff” by ensuring the representation of a diverse Indian society including, but not limited to religious or ethnic minorities.19 In response, the Indian government expanded the eligibility criteria for a chairperson to include a person who has been Supreme Court judge without adequate legislative consultation.20 Earlier, only a person who had been the Chief Justice of India was eligible for the position of a chairperson. Similarly, despite the SCA’s recommendation to amend the PHRA, the legislation continues to empower the Indian government to recruit a civil servant with the rank of Secretary to the Government for the role of Secretary General of the NHRCI.21 This stands squarely in violation of the Paris Principles that are premised on independence from government interference. A civil society analysis of the recruitment for chairpersons in the other concurrent thematic commissions on minority rights, child rights, women, persons with disabilities and backward classes, between 2018 and 2023 demonstrate that such recruitments continue to act as defacto extensions for former government servants or parliamentary members associated with the ruling political party.22 This constitutes a direct attack on the independence of the commissions and stands to compromise their autonomy.

We also reiterate our concerns about the opaque selection process characterised by diminishing opposition voices. According to the PHRA, the chairperson and other members of the NHRCI are appointed by the President based on the recommendation of a committee consisting of the Prime Minister, the Speaker of the House of the People (Lok Sabha), the Minister of Home Affairs, the Leader of the Opposition in the House of the People (Lok Sabha), the Leader of the Opposition in the Council of States (Rajya Sabha), and the Deputy Chairperson of the Council of States (Rajya Sabha).23 However, since 2019 the post of the opposition leader in the Lok Sabha has been vacant, leaving only a single opposition voice in the selection committee, with all others belonging to members of the ruling political coalition. In this background, it is hardly surprising that the current NHRCI chairperson, Justice Arun Kumar Mishra, who has delivered several judgements in favour of the government and against marginalised populations24 continues to hold the position despite heavy criticism from the political opposition including Mallikarjun Kharge, the sole opposition voice in the selection committee and civil society.25

Further, in November 2023, the NHRCI appointed seven former officers of the Indian Police Service as special monitors.26 One of the officers was accused of corruption in 2018 while working as Special Director of Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), India’s federal investigation agency.27 The person has been given the responsibility to oversee the thematic areas of terrorism, counterinsurgency, communal riots and violence.28 We also remain concerned about the appointment of a former director of the national Intelligence Bureau as a member of the commission.

29 As highlighted in the earlier letter, the appointment of a former high-level intelligence and security official in the decision- making body of the commission is clearly contrary to the Paris Principles.30 The Intelligence Bureau has been known for targeting civil society organisations for opposing projects that harm the environment and accused them of backing armed groups – accusations that have acted as barriers for organisations to secure funding and operate freely.31 During the 2023 review, the SCA had also noted that three of the six positions in the NHRCI remain vacant.32 Two of the three positions remain vacant to date. It had also highlighted the lack of gender balance in leadership positions with only 95 out of 393 staff positions held by women in the NHRCI.33

Lack of cooperation with human rights bodies

During the March 2023 review, the SCA had taken note of the NHRCI’s lack of effective engagement with civil society and human rights defenders (HRDs) in India and recommended additional steps to increase its cooperation with them outside of the Core Groups of non- governmental organisations (NGOs) and HRDs that the NHRCI has created.34 The SCA had also recommended the NHRCI to interpret its mandate in a “broad and purposive manner to promote a progressive definition of human rights”.35 It had also called upon the NHRCI to address all human rights violations and ensure consistent follow up with state authorities.36 In August 2023, the NHRCI held the first meeting of the re-constituted Core Group on NGOs and HRDs but failed to take note of the deliberate and sustained targeting of religious minorities and human rights defenders under a range of overly broad and vague laws and policies, leading to hate crimes, particularly against Muslims,

Christians and Dalits.37 It also failed to recognise the ongoing erosion of their human rights, including access to education, employment, housing, and violations of their rights to freedom of expression, religion, association and to non-discrimination, which continue to go unpunished. Instead, in what can be perceived as a tokenistic gesture, the NHRCI announced national and lifetime awards for human rights defenders while numerous human rights defenders languish in detention without trial under various draconian laws including the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) – India’s primary counter terrorism law for years now.38 This includes the 16 human rights defenders, nine of whom continue to be detained in connection with the Bhima Koregaon-Elgar Parishad case for more than five years now;39 Kashmiri human rights defender Khurram Parvez who has been in detention since November 2021;40 and Muslim student activist Umar Khalid and other human rights activists whose bail appeals in connection with the February 2020 Delhi riots have been repeatedly denied by various courts since October 2020.

41 The NHRCI has not taken any concrete steps to respond to the situation of the HRDs or intervene in a timely manner despite various UN special rapporteurs calling on Indian authorities to release the HRDs.42 It has also failed to take meaningful and timely action on the rising ethnic violence in Manipur which started in May 2023,43 the intensification of repression in Jammu & Kashmir after the abrogation of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution in August 2019,44 the communal violence in Haryana in August 2023,45 Uttarakhand in June 2023,46 the human rights violations during the February 2024 farmers protests,47 the misuse of the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act48 that has been used to silence peaceful dissent, and the Citizenship Amendment Act that was operationalised on 11 March 2024.49 Human rights defenders have also repeatedly raised concerns about the inordinate delays by the NHRCI to effectively dispose of cases.50

Further, in March 2022, the Asia Pacific Forum (APF), a coalition of national human rights institutions in the Asian region, including the NHRCI, released a Regional Action Plan for HRDs as mentioned under the 2018 Marrakesh Declaration that established a global framework of actions by national human rights institutions to support the rights of HRDs.51 However, the NHRCI failed to acknowledge let alone discuss the Action Plan during the meeting of the Core Group. In another insincere effort to feign cooperation, in September 2023, just four days before the 2023 G20 summit was hosted by India, the NHRCI convened a last-minute meeting with civil society organisations, resulting in a rushed and inadequate consultation.52

The cumulative picture that emerges reflects the NHRCI’s and the Indian government’s clear lack of political will to act and the apparent reluctance to effectively respond to and address the deteriorating human rights violations in the country and to uphold transparency and accountability. The failure to create a truly independent NHRCI stands to perpetuate impunity and hinder any effort to ensure that the Indian authorities respect and uphold human rights. Therefore, taking into consideration the clear defiance of the SCA’s recommendations in 2006, 2011, 2016, 2017 and most recently in 2023, by the NHRCI, we strongly urge your office to evaluate the NHRCI’s rating carefully during the upcoming accreditation process.

We also write to inform that we intend to publish the letter on Tuesday, 26 March 2024 on our website. The letter may also be uploaded on the websites of the other co-signees.

Yours sincerely,

Amnesty International

CIVICUS: World Alliance for Citizen Participation

CSW

FORUM-ASIA

Front Line Defenders

FIDH (International Federation for Human Rights), within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders Human Rights Watch International Service for Human Rights (ISHR) World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders.

INDIA: VIOLENCE MARKS RAM TEMPLE INAUGURATION

(New York) – Indian authorities should urgently act to prevent further escalation in communal violence following the consecration of a controversial Hindu temple in Uttar Pradesh state on January 22, 2024, Human Rights Watch said today. Hindu processions that day led to sectarian clashes as well as incidents of vandalism, threats, and assault against Muslims and other religious minorities in several parts of the country.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who led the temple inauguration, had warned that those celebrating the temple should “show faith, not aggression.” However, as thousands of supporters of Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) joined cavalcades of vehicles across the country and shouted the slogan “Jai Shri Ram,” endorsing the god Ram, communal skirmishes broke out in a number of states including in Karnataka, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, Kerala, Maharashtra, and Telangana. “Prime Minister Modi’s explicit instructions against aggression often went unheeded, a casualty of violence emboldened by longstanding impunity, political patronage and protection,” said Elaine Pearson, Asia director at Human Rights Watch.

“Indian authorities need to take stronger action to end human rights abuses by Hindu militants.” The most concerning incidents occurred in Maharashtra state, where a coalition government that includes the BJP took office in June 2022. In the Mira Road suburb of the state capital, Mumbai, arguments between Hindu men participating in a temple procession and Muslim residents soon flared into violence. The police arrested 13 men allegedly implicated in the violence. Muslim witnesses said that in the evening before the temple inauguration, brawls broke out when Hindu mobs chanted slogans while brandishing sticks and swords in front of a mosque. When a militant Hindu mob returned to the same area on January 23, pelting stones and attacking shops, the police did little to control them. “The police are defending only one side,” Azeemuddin Sayed, a local social worker, told Human Rights Watch. “They should protect everyone. Or will they only protect based on religion?”

Abdul Haq Chaudhary said that the mob attacked his son and two workers, and damaged his vehicle. “They asked my son to chant ‘Jai Shri Ram,’ and when he refused, they started beating him,” Chaudhary said. He said that the mob attacked after they identified their vehicle as Muslim-owned as it had Islamic symbols. Chaudhary said he had filed a complaint, but the police had yet to make any arrests. “We have all the information. But the police are making excuses and saying they cannot spot anyone in the CCTV footage.” After the Mira Road violence, the municipal authorities brought in bulldozers to demolish alleged illegal structures, most of them belonging to Muslims, that had been standing for decades. Local activists alleged that the government actions resulted in summary and collective punishment against Muslim residents.

Even as Prime Minister Modi declared on January 22 that the Ram temple was “a symbol of peace, patience, harmony and coordination in Indian society,” over a dozen instances of violent clashes were recorded across several Indian states. Many followed a similar pattern of young Hindu men displaying aggression, publicly brandishing sticks, swords, and in one case a gun. Violence did not escalate after the police intervened, showing that when ordered to do so, law enforcement can act in a rights-respecting manner, Human Rights Watch said.

A Muslim woman in Mumbai alleged that men chanting “Jai Shri Ram” harassed her on the streets. In Karnataka state, police arrested four men after a 17-year-old Dalit boy was assaulted and forced to say “Jai Shri Ram” for insulting Hindu gods because he had included a photo of the Dalit leader Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar on his WhatsApp status. Hindu mobs in Bihar celebrating the temple consecration allegedly set ablaze a Muslim cemetery. In Uttar Pradesh, police arrested 11 people after the caretaker of a Mughal-era mosque in Agra complained that members of a Hindu procession forcibly placed saffron flags – symbolic of Hinduism the structure.

In the state’s Sant Kabir Nagar district, police arrested five local residents who allegedly tried to enter a mosque twice while celebrating the temple consecration in a procession on January 22. In Telangana state, Muslim residents filed a police complaint after members of a Hindu procession allegedly threw shoes and papers at a mosque. In some places, the violence followed confrontations between local Muslim and Hindu residents. In Gujarat, some threw stones when members of a Hindu procession lit firecrackers and played loud music in a Muslim neighborhood. In Telangana’s Sangareddy district, mobs set a shop on fire after an argument in which someone there a shoe at the Hindu procession. In Panvel, Maharashtra, a scuffle ensued in a Muslim-dominated neighborhood after local residents confronted men chanting “Jai Shri Ram.”

In Nagpur district, a brawl ensued between local Muslim residents and Hindu men celebrating the consecration. A communal clash in West Bengal on January 24 left at least 14 people injured. The consecration of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya is widely seen as a culmination of Hindu majoritarian and political demands led by the ruling BJP and its affiliates. The temple was constructed around the site where the 16th century Babri Mosque stood until a Hindu mob demolished it in 1992. Many Hindus believe that the mosque had been built on the ruins of a previous temple marking the birthplace of the Hindu god Ram.

Thousands died in religious clashes and riots across the country following the demolition. Secular and liberal groups in India organized screenings of documentaries during the temple inauguration to recall the brutalities that had marked the campaign for its construction. Both the authorities and Hindu groups targeted the screenings. In Hyderabad, three people were arrested after members of a Hindu group filed a complaint and allegedly vandalized the screening, accusing its organizers of “creating a communal issue.” In Kerala, a Hindu mob threatened students of KR Narayanan National Institute of Visual Arts and Sciences, and disrupted the screening of the same documentary on the evening of January 22.

In Pune, several men chanting slogans entered the Film and Television Institute of India to protest the screening of a documentary criticizing the Ram temple movement, vandalized the premises, and attacked students. The authorities should act immediately to stem the deteriorating human rights situation in the country, particularly for freedoms of religion, expression, and association, Human Rights Watch said. Ahead of elections slated for this year, it is crucial to address rising fears of violence and discrimination against India’s Muslims and other religious minorities. “A political campaign that enables violent triumphalism harms governance, rule of law, and India’s reputation as a democracy,” Pearson said. “The authorities need to ensure that the law is enforced impartially, and not to the benefit of the ruling party’s supporters.” inauguration

Feb 20, 2024 Foreign Affairs INDIA’S FEET OF CLAY

How Modi’s Supremacy Will Hinder His Country’s Rise This spring, India is scheduled to hold its 18th general election. Surveys suggest that the incumbent, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is very likely to win a third term in office. That triumph will further underline Modi’s singular stature. He bestrides the country like a colossus, and he promises Indians that they, too, are rising in the world. And yet the very nature of Modi’s authority, the aggressive control sought by the prime minister and his party over a staggeringly diverse and complicated country, threatens to scupper India’s great- power ambition

INDIA: FUNDAMENTAL FREEDOMS DETERIORATE FURTHER IN MODI’S SECOND TERM

India will hold the world’s largest national election over almost seven weeks starting from 19 April 2024 to choose its next Prime Minister and fill the 543 seats of the Lok Sabha, the lower house of parliament. The election is taking place within a context of restricted freedoms. Since the nationalist conservative Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi won a second consecutive term in 2019, there has been an alarming deterioration of fundamental freedoms and civic space in India. Over the past 10 years, the Modi government and BJP supporters have attempted to silence dissent by targeting critics including civil society groups, human rights defenders and independent media.

The government uses the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), a draconian anti-terror law, and other repressive laws to target, harass, intimidate and detain activists, human rights defenders and journalists on fabricated and politically motivated charges in response to their work. The authorities also block access to foreign funding for civil society organisations (CSOs) through the restrictive Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA). Human rights defenders and journalists in Indianadministered Jammu and Kashmir also continue to be targeted. Due to this, the CIVICUS Monitor, a global initiative to track the state of civic freedoms, downgraded India’s rating to repressed in 2019, the secondworst rating available.

Further, the National Human Rights Commission of India (NHRCI), which lacks independence and accountability, has repeatedly failed to deliver on its mandate, in particular to protect the rights of people, especially human rights defenders. The Indian government’s actions are in contravention of its international human rights obligations to protect freedoms of association, expression and peaceful assembly under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which it ratified in 1979.

Further, in March 2023, the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council adopted India’s Universal Periodic Review, with around 30 recommendations relating to civic space. The government accepted recommendations to ensure a safe and enabling environment for civil society and noted recommendations to review restrictive laws, including the FCRA and UAPA. However, there has been no progress in implementing the recommendations to date. Modi is running for his third term in the election and there are serious concerns about a pre-election crackdown on his political opponents, with raids and arrests by federal agencies. This brief will highlight how these actions reflect a pattern of repression by the Modi government to undermine democracy and civic space, as documented by the CIVICUS Monitor.

PORTFOLIOS OF HATE

‘Portfolios of Hate’ comprises a curated list of non-exhaustive of 70 instances of hate speech, meticulously recorded by national media houses from across various regions in India. Of the 70 incidents analysed, involving 36 personalities, a striking trend emerges. During the first term of the BJP-led NDA government (2014-2019), 23 incidents of hate speech were recorded. However, this number doubled during the second term (2019-2024), with 47 cases reported. This significant surge in hate speech instances underscores the re-ascendance of Hindutva ideology to parliamentary power. It has emboldened politicians to propagate Islamophobia, Xenophobia, and other forms of targeted hate with impunity.

UNITED STATES COMMISSION OF INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FAITH (USCIRF) ANNUAL REPORT 2024: INDIA

‘HATE THY NEIGHBOR’ AS AN ELECTION SLOGAN IN MODI’S INDIA

India’s Narendra Modi seems to have decided that he can win a third five-year term as prime minister only through campaign rhetoric targeting the Muslim religious minority as a threat not just to national security, but to the 80 percent Hindu majority among the country’s

1.40 billion people. Muslims, in the census last held in 2011, account for just under 15 percent, with Christians at a little over 2.30 percent.

The Election Commission of India, its three members handpicked by Modi from among the pool of his former officials in Gujarat, where he was chief minister for 14 years, and in New Delhi since he became prime minister in 2014, has been deaf to loud protests by civil society which is monitoring the elections carefully. On May 11, civil society groups protested against the election commission for its inaction on violations of the model code of conduct by Modi, saying the officials should “grow a spine or resign.” Former judges, retired election officials, bureaucrats, military officers, professors, artists and editors, are apprehensive that the ruling Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) may take extreme measures in the general elections now underway to blunt popular anger against Modi’s policies that have impacted employment, agriculture, education and social harmony.

Religion is seen as the super weapon in this no-hold-barred election — a “Brahmastra,” a divine force. Modi styles himself as the “Hindu Hriday Samrat,” or “he who rules the hearts of the Hindus.” He sought to appease his ‘vote bank’ by rushing through the consecration of a still-incomplete Ram temple being built on the ruins of the 500-year- old Babri mosque in Ayodhya which was demolished by rapturous mobs in 1992. It did not work. “Modi and his long-term friend and Home Minister Amit Shah seem to have shocked even some of their cabinet colleagues” In a wink, he fell back on rousing anti-Islam passions, a tried and proven tactic that has often worked for right-wing politicians since the Indian subcontinent’s bloodstained partition in 1947.

Modi had successfully used targeted hate against Muslims in retaining power in Gujarat, and then as the engine of his electoral campaigns to become prime minister in the general elections of 2014 and 2019. In the general elections, he had deftly padded them with promises of “Acche Din” or “better days,” and a return to the golden age of Hindu mythology. But the gloves are off this time. Modi and his long-term friend and Home Minister Amit Shah seem to have shocked even some of their cabinet colleagues and allies with their vitriolic lampooning of Muslims.

The opposition parties, who are part of the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA), are accused of harboring and nurturing people successively described as termites, traitors, saboteurs, infiltrators, seducers of Hindu women in alleged ‘love jihad,” and in final imagery, creatures out to displace Hindus from their homeland. The last was through a vicious short animated film. It shows the Muslim as a Cuckoo bird, the South Asian Cuculidae. The bird is well known for its sharp song in the summer months. But, alas, it is better known for laying its eggs in the nests of crows and much smaller songbirds. The chick hatches, grows big very fast, expels and kills its weaker nest mates, till, finally, it alone survives.

This was a short film shown as election advertising on paid and unpaid social media. The imagery will not be lost on a four-year-old child. It was not lost on the electorate. It took a long and bitter fight by civil society, first with the lethargic election commission, and in courts of law, before the animated film was proscribed. No one has been punished so far. India, like its neighbor Pakistan, has perhaps the world’s most stringent law against blasphemy and targeting of religious communities. Blasphemy not just against the God of Abraham, but against any god, of the millions in the Hindu pantheon, for instance.

“The BJP has repeatedly used religious tropes in its poll pitch and incited communal feelings” No one calls them anti-blasphemy laws anymore, and many have forgotten they are remnants of the penal code enforced by the colonial British Raj to maintain a semblance of law and order amidst India’s myriad religions, caste, and groups competing for scarce resources and fiercely guarding ‘purity’ lines.

The United Kingdom does not have this on its statutes anymore. Pakistan uses it, not unsparingly, to keep in check its tiny Christian population and its various Islamic sects such as the Shias, the Sufis, and the Ahmedias. Several sections of the Indian penal code call for action for hurting religious feelings or doing anything that can cause friction or violence between communities, including insulting religions and religious communities. These precautions have been carried over to the laws and rules governing elections and are an intrinsic part of the model code of conduct applicable to political parties and candidates.

As expected by a cynical civil society and political activists, election officials have been quick to act against opposition candidates if they fall foul of these regulations. Samajwadi (socialist) Party leader Maria Alam Khan at a public rally in Uttar Pradesh called upon her electorate to participate in a “vote jihad,” saying that voting as a religious duty was necessary to defeat the ruling party. Within hours, the election commission set up a “flying squad,” ordering the police to take action.

The BJP and its leaders seem to be immune to the law. With phases of the seven rounds over in this general election, the BJP has repeatedly used religious tropes in its poll pitch and incited communal feelings. Its official social media handles have shared such content and its leaders have openly made anti-Muslim remarks. The award-winning portal, Alt News, has exposed how the ruling party used the Hindu god Ram to stoke religious sentiments alleging that Congress leader Rahul Gandhi plans to lock up the temple gates. Modi said at an election rally in Dhar, in central Madhya Pradesh state on May 7, “...Modi needs 400 seats so that the Congress does not put a ‘Babri lock’ on the Ayodhya Ram Temple...” The Congress shall provide a quota based on religion in contracting, Modi claimed.

“They are also planning to prefer minority communities over others in sports, they will be deciding who will be selected for the cricket team based on religion. I want to ask Congress today, if this was your intention all along why did you break apart the country into three parts in 1947? You should’ve declared the country as Pakistan back in 1947 and removed the existence of India.” Lesser leaders have been outright vulgar. BJP legislator from southern Telangana state, T Raja Singh, in a recent video clip, can be seen singing from a campaign stage that strongman Modi will throw out all Pakistani mullahs. Sharing the hate video, right-wing influencer Sunanda Roy praised the courage of the legislator.

BJP’s youth leader Tejaswi Surya, a sitting MP has repeatedly targeted Muslims in Karnataka and other states. He tells the women present in the audience that the INDIA bloc and Congress will make them wear burqas. He also claimed that the Congress manifesto proposed the implementation of sharia law and would give freedom to Muslims for cow slaughter.

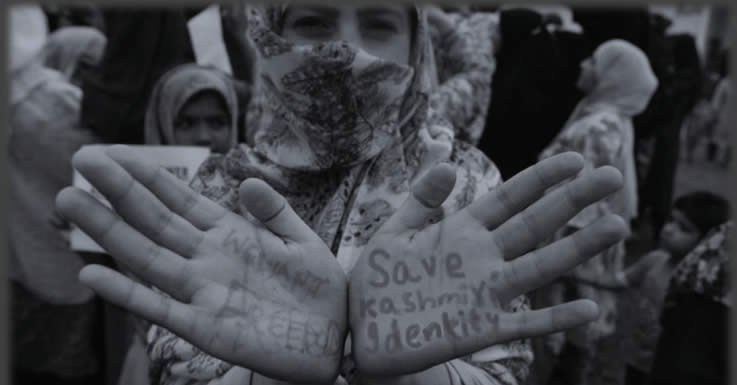

OIC GENERAL SECRETARIAT REITERATES ITS CALL FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION OF UN SECURITY COUNCIL RESOLUTIONS ON JAMMU AND KASHMIR

As 5 January 2024 marks 75 years since the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP) unanimously adopted a resolution espousing the right to self-determination of the Kashmiri people through a free and impartial plebiscite under the auspices of the United Nations, the General Secretariat of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) reiterates its call on the international community to honor the UNCIP decision, which is upheld by the United Nations Security Council in its subsequent resolutions. The General Secretariat reaffirms the OIC’s support for the Kashmiri people’s inalienable right to self- determination, and for the final settlement of the Jammu and Kashmir dispute in accordance with the relevant UN Security Council resolutions and calls again on the international community to ensure the implementation of those resolutions.

ORAL STATEMENT ON ITEM 4: GENERAL DEBATE UN HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL 55TH

Mr. President,Amnesty International highlights here some of the many human rights situations that it is following with concern. Amnesty International continues to document serious human rights violations in Ethiopia. Members of this Council must take immediate steps to resume scrutiny of the human rights situation in Ethiopia and establish a process to follow up on the findings of the International Commission of Human Rights Experts on Ethiopia. On China Amnesty International condemns the recent passage of Hong Kong’s Safeguarding National Security Ordinance contrary to Hong Kong’s human rights obligations, and calls for it not to go into effect.

We further call on this Council to follow up on OHCHR’s assessment on Xinjiang published in 2022, request further updates from the High Commissioner and pursue options for accountability including through the establishment of an independent, impartial and international mechanism. Finally, in India, minorities continue to face violations of their right to education, housing, work, religion, employment and nationality. Recent events in Manipur and the intensification of repression of the people of Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir are illustrations of this. Coupled with the rising advocacy of hatred and violence against minority and marginalized groups by the member of the ruling political party and their supporters, this has instilled a grave sense of insecurity and fear.

The government has imposed dangerous restrictions on civil society by weaponizing laws to criminalise freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association. The gradual weakening of autonomous institutions such as the National Human Rights Commission of India has profound implications on people’s ability to enjoy their human rights. We call on States through this Council to address these violations, including in the context of the Council’s prevention mandate. Thank you.

CONDEMNATION AND CALL FOR THE IMMEDIATE RELEASE OF KASHMIRI JOURNALIST IRFAN MEHRAJ

Justice For All Canada vehemently condemns the recent arrest of Kashmiri journalist Irfan Mehraj by Indian authorities. During a professional assignment on March 20, 2023, Mehraj was summoned for questioning and arbitrarily detained by India’s National Investigation Agency (NIA) in Srinagar under provisions of the Indian Penal Code and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. [1] Mr. Mehraj’s arrest, based on allegations of association with the globally recognized human rights organization named the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS), is a blatant affront to freedom of speech and expression. The JKCCS has played a pivotal role in documenting extensive human rights violations in Kashmir and providing vital information to the United Nations. [2]

Mehraj is facing several politically motivated charges, including allegations of ‘sedition’ and ‘funding terror activities,’ along with Khurram Parvez, an internationally recognized human rights defender and the Program Coordinator for JKCCS. Parvez has been held in arbitrary detention for over two and a half years. The NIA singled out Mehraj on the basis of his association with Khurram Parvez, describing him as ‘a close associate.’ Currently, both Mehraj and Parvez are detained in pre-trial custody at the maximum-security Rohini prison in New Delhi, India. [1] The targeting of Mehraj is not an isolated incident but ratheremblematic of the broader pattern of harassment and intimidation faced by Kashmiri journalists since 2019. As outlined by the United Nations, such practices by the Indian government are designed to delegitimize human rights work and obstruct the monitoring of human rights abuses in the region.

This suppression of free speech contravenes international human rights law, including Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as well as Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. As the founding editor of Wande Magazine and a contributor to Two Circles.net, Mehraj’s journalistic endeavours have extended to reputable international media outlets such as Al Jazeera, TRT World and Deutsche Welle. [2] The arrest has sparked condemnation from prominent voices, including Amnesty India, Human Rights Watch, and UN Special Rapporteur Mary Lawlor. All have called for Mehraj’s immediate release, emphasizing the need to protect human rights defenders.

Additionally, the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and former Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti have voiced concerns over Mehraj’s targeting for exposing human rights violations. The Journalist Federation of Kashmir has also denounced the arrest, reporting Mehraj’s transfer. Furthermore, the Free Speech Collective has criticized the arrest as evidence of authorities’ efforts to suppress independent journalism. This widespread condemnation underscores the urgency of the situation and the global solidarity in demanding justice for Mehraj and the protection of press freedom in Kashmir. [2]

New Delhi’s deployment of over half a million soldiers to quash Kashmiris’ aspirations for self- determination underscores the oppressive tactics employed by the Indian government. The systematic detention of Kashmiri political figures under laws like the Public Safety Act and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, under spurious charges related to “terrorism,” “receiving foreign funding,” and “abetting secession,” are a grave violation of human rights. The draconian nature of these laws (such as the inclusion of a 180-day pre-trial detention period, which can be increased) has been criticized for violating international human rights standards. [3]

Rights organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and the United Nations have extensively documented severe human rights abuses perpetrated by the Indian army, often with governmental support. In addition, the Washington-based Genocide Watch has sounded alarms regarding India’s human rights abuses in Kashmir, and has called upon the United Nations to prevent a genocide in the region. India’s Hindu-nationalist regime’s unilateral revocation of Kashmir’s special autonomous status in 2019, purportedly to combat “terrorism,” has led to a relentless assault on press freedom. Journalists like Kashmiri counterparts Fahad Shah and Asif Sultan have been unjustly imprisoned under laws designed to deny them bail.

“We urge the Canadian government to unequivocally denounce the arbitrary arrest of Irfan Mehraj and demand his immediate release,” stated Taha Ghayyur, Vice-President of Justice For All Canada. “Journalists like Mehraj are indispensable in upholding democratic values and exposing human rights abuses. Canada must staunchly defend press freedom and human rights, both domestically and internationally,” he added. Justice For All Canada demands the immediate and unconditional release of Irfan Mehraj and calls upon the Indian government to fulfill its international obligations to safeguard journalists’ rights and ensure freedom of speech and expression, particularly in Kashmir.

We stand in solidarity with Irfan Mehraj, Kashmiri journalists, human rights defenders, and all those advocating for justice and human rights in Kashmir. Given the severity of the situation, Justice For All Canada implores the Canadian government to initiate a parliamentary investigation into: the arbitrary detentions of Kashmiri civil and political leaders, the egregious human rights violations perpetrated by the Indian army, India’s use of draconian legislation such as the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act and its non- conformity with international law.

INDIA: TECHNOLOGY USE SHOULDN’T UNDERMINE FREE, FAIR ELECTIONS

(New York) – Voters in India will cast their ballots in a six-week general election beginning April 19, 2024, amid concerns that Indian authorities exert considerable control over the digital ecosystem that can make for an uneven playing field, Human Rights Watch said in a question-and-answer document released today. The party or coalition of parties that wins a majority of 543 seats in the lower house of Parliament will nominate a candidate for prime minister and form a government. Human Rights Watch examined potential threats to India’s online environment ahead of the elections. The authorities have increased their control over digital platforms and amassed extensive amounts of personal data, which may affect the campaign environment. Human Rights Watch details the additional steps technology companies should take to meet their human rights responsibilities in this election.

“The risk of misuse of technology in India’s election is significant and could result in further tilting the playing field in favor of the ruling party,” said Deborah Brown, acting associate technology and human rights director at Human Rights Watch. “The Election Commission of India should ensure that all political parties comply with the model code of conduct and that their use of technology in campaigning respects human rights.” Human Rights Watch reviewed popular companies’ policies and found that all companies could do more to address any aspects of their products, services, and business practices that may cause, contribute, or be linked with undermining free and fair elections.

Indian political parties campaign extensively through digital platforms. Ahead of the upcoming elections, political advertising on Google surged in the first three months of 2024. The governing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been the largest advertiser among political parties on both Google and Meta over the past three months, and has built a massive messaging operation through WhatsApp. In recent years, Indian authorities have applied significant formal and informal pressure on tech companies, both to suppress critical speech and to keep online speech by government-aligned actors that would otherwise violate platforms’ policies. India shuts down the internet more than any other country, with the authorities frequently using internet shutdowns to stem political protests and criticism of the government, violating domestic and international legal standards.

Misuse of personal data, which can contain sensitive and revealing insights about people’s identity, age, religion, caste, location, behavior, associations, activities, and political beliefs, is a major concern in India’s elections. India has developed an extensive digital public infrastructure through which Indians access social-protection programs. The Indian government has collected massive amounts of personal data in the absence of adequate data protection laws to prevent misuse of this data during campaigning and to properly protect privacy rights.

There have already been reports of misuse of personal data in the campaign period, which started on March 16. On March 21, the Election Commission told the government to stop sending messages promoting government policies to voters, as it was a violation of the campaign guidelines. The message and accompanying letter from Prime Minister Narendra Modi to which it referred, had sparked concerns over data privacy as well as abuse of government communications for political purposes.

Social media platforms have come under scrutiny in recent years for failing to adequately invest in and address the use of their platforms to undermine participation in democratic elections. In India, Meta has faced criticism for failing to curb the spread of hate speech and incitement to violence, and for contributing to give the BJP an unfair advantage in political campaigning online during past elections. The widespread availability of low-cost generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools that require little technical expertise raises new concerns. Generative AI can be used to create deceptive videos, audio recordings, and images impersonating a candidate, official, or media outlets.

These are disseminated quickly across social media platforms, potentially undermining the integrity of the election or inciting violence, hatred, or discrimination against religious minorities. In the lead-up to the 2024 elections, several parties are using AI in their campaigns. Companies should resist threats from the authorities when responding to government requests for data or content removals, Human Rights Watch said. T

hey should treat all parties and candidates equitably, especially when it comes to addressing speech that incites violence or hatred. Under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, companies have a responsibility to respect human rights and remedy abuses, including by addressing any aspects of their practices that contribute to undermining the right to participate in democratic elections. “Ahead of India’s elections, tech companies need to demonstrate that their commitment to human rights is more than words,” Brown said. “This means adequately investing in content moderation, carrying out rigorous human rights impact assessments, and meaningfully engaging with civil society.

BJP WIN IN INDIA’S 2024 GENERAL ELECTION ‘ALMOST AN INEVITABILITY’

India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, has cut a confident figure in recent weeks. As his Bharatiya Janata party (BJP) swept three major state elections in December, Modi did not hold back from predicting that “this hat-trick has guaranteed the 2024 victory” It was a sign that with less than six months to go before the general election, in which Modi will be seeking a third term in power, campaign season has begun with gusto.

In India’s current political landscape, the consensus among political analysts is that a win for Modi and the BJP is the most plausible outcome. The prime minister’s popularity as a political strongman, alongside the BJP’s Hindu nationalist agenda, continues to appeal to the largeHindu majority of the country, particularly in the populous Hindi belt of the north, resulting in the widespread persecution of Muslims. At state and national level, the apparatus of the country has been skewed heavily towards the BJP since Modi was elected in 2014. He has been accused of overseeing an unprecedented consolidation of power, muzzling critical media, eroding the independence of the judiciary and all forms of parliamentary scrutiny and accountability and using government agencies to pursue and jail political opponents.

While regional opposition to the BJP is strong in pockets of south and east India, nationally it is seen as fragmented and weak. The main opposition Indian National Congress party won the state election in Telangana this month but is in power in only three states overall and is perceived as hierarchical and riddled with infighting. The recently formed coalition of all major opposition parties – which goes by the acronym INDIA – has yet to unite on crucial issues, though it has vowed to fight the BJP collectively. “The general sense is that a BJP win is almost an inevitability at this stage,” said Neelanjan Sircar, a fellow at the Centre for Policy research.

“The question is more: what factors will shape the scale of the victory?” The BJP has begun a nationwide pre-election push. A roadshow, titled Viksit Bharat Sankalp Yatra, will see thousands of government officers deployed to towns and villages across the country over the next two months, tasked with speaking about the BJP’s successes over the past nine years – despite criticisms of politicising government bureaucracy and resources for campaigning purposes. The Ministry of Defence is also setting up 822 “selfie points” at war memorials, defence museums, railway stations and tourist attractions where people can take photos of themselves with a Modi cutout.

The BJP’s recent domination in the states of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chattisgarh appeared to reaffirm the popularity of Modi. Though the prime minister has little to do with state elections, which are designed to elect local assembly members, the BJP strategically put Modi front and centre of their campaigns in the place of local leaders, where he appeared at dozens of rallies to directly appeal to voters and present himself as the embodiment of the party. Modi’s messaging in these campaign speeches combined an emphasis on the BJP’s paternalistic welfare schemes – which provide large amounts of free food and cash handouts – with nationalistic and religiously communal rhetoric, offering a glimpse of how the BJP intends to fight the election on a national scale.

Modi’s role in elevating India as a global power – be that in international politics or in the recent its moon landing in August – it was the first country to successfully land a spacecraft near the lunar south pole – was also prominent. Asim Ali, a political scientist, said the recent state election campaigns in the north were “some of the most religiously polarising I have seen” as the BJP played heavily on Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) sentiments to win the majority vote. In Rajasthan, Modi repeatedly evoked an incident where a Hindu tailor was murdered by extremist Muslims to claim that the opposition Congress party, which ruled the state, was “sympathetic to terrorists” and that it was their appeasement of Muslims that had led to the killing.

The BJP’s candidates included four Hindu priests, some with very hardline views, but no Muslims. In the tribal dominated state of Chhattisgarh, the BJP played on fears of forced conversions of tribal people away from Hinduism. Modi was brought to power in 2014 largely on the back of an anti- incumbency wave while his re- election victory in 2019 was all but secured after India carried out airstrikes on Pakistan, after a terrorist incident a few months before the polls, resulting in a storm of national security sentiment in his favour.

However, whether the BJP will win the same sort of sweeping parliamentary majority it secured in 2019 is unclear. Its position in certain crucial states, such as Bihar and Maharashtra, is uncertain and the party’s weakness on economic problems, particularly jobs and inflation, could also affect voting. Ali was among those who feared a Hindu-Muslim divide would be stirred up further to become “the dominant issue, at least in the Hindi heartland”. “Hindu-Muslim communalisation has become completely normalised, not just through political campaigning but by the television news channels and the messages people see on social media and WhatsApp,” said Ali.

“It can be activated by the BJP at their grassroots at any time. Just one or two slogans from Modi and other senior BJP leaders, a few coded communal dog whistles, and people get the message.” Indeed, one of the biggest issues likely to dominate the BJP’s agenda pre-election is the long-awaited opening of the Ram Mandir, a grand Hindu temple that has been built in the place of a demolished mosque. Construction of the building, in the north Indian town of Ayodhya, has long been a focal point of the Hindu nationalist movement in India, and the fanfare around Modi’s inauguration of the temple later this month in January is expected to be a national event. Baijayant Panda, national vice president of the BJP, said the party was very confident about the parliamentary elections. He credited the confidence in part to “the Modi premium”, which meant the BJP tended to perform better in national than state elections because of the “stratospheric popularity” of the prime minister.

“On the ground, there’s a huge surge of optimism, even in areas which we haven’t traditionally won,” said Panda. “Having had this kind of victory in the state elections completely cements our position.” Exactly what a third term for Modi would mean for India, particularly if it was another outright majority, was a cause for concern among some analysts and human rights groups. While Panda said it would be defined by economic success, and India becoming the world’s third largest economy, others feared a continued erosion of democracy and the rights of the Muslim minority, who exceed 200 million.

Ashutosh Varshney, the director of the Center for Contemporary South Asia at Brown University in the US, said he expected the rights of Muslims to continue to come under attack. He warned that a situation similar to the Jim Crow laws, which existed in southern American states in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and disenfranchised black people on the basis of race, could become a reality in India under a third Modi term.

“If Modi comes back to power we can imagine a scenario of a Jim Crow-style Hindu nationalist order in BJP-ruled states,” said Varshney. “It will establish Hindu supremacy, deprive Muslims of equality and create a secondary citizenship for Muslims, which will likely eventually remove their right to vote.” Panda pushed back against allegations of BJP communalism. “I dare anyone to point out where a minority, whether a Muslim or a Christian or Buddhist or a Sikh has been discriminated against in the governance of India, you will not find a single example,” he said

NDIA: INCREASED ABUSES AGAINST MINORITIES, CRITICS

(Bangkok) – The Indian government undermined its aspirations for global leadership as a rights- respecting democracy during 2023 with its persistent policies and practices that discriminate and stigmatize religious and other minorities, Human Rights Watch said today in its World Report 2024. The Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led government also arrested activists, journalists, opposition politicians, and other critics of the government on politically motivated criminal charges, including terrorism.

“The BJP government’s discriminatory and divisive policies have led to increased violence against minorities, creating a pervasive environment of fear and a chilling effect on government critics,” said Meenakshi Ganguly, deputy Asia director at Human Rights Watch.“Instead of holding those responsible for abuses to account, the authorities chose to punish the victims, and persecuted anyone who questioned these actions.” In the 740-page World Report 2024, its 34th edition, Human Rights Watch reviews human rights practices in more than 100 countries. In her introductory essay, Executive Director Tirana Hassan says that 2023 was a consequential year not only for human rights suppression and wartime atrocities but also for selective government outrage and transactional diplomacy that carried profound costs for the rights of those not in on the deal. But she says there were also signs of hope, showing the possibility of a different path, and calls on governments to consistently uphold their human rights obligations.

Indian authorities harassed journalists, activists, and critics through raids, allegations of financial irregularities, and use of the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act, which regulates foreign funding of nongovernmental organizations. In February, Indian tax officials raided the BBC offices in New Delhi and Mumbai in an apparent reprisal for a two-part documentary that highlighted Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s failure to provide security for Muslims. The government blocked the BBC documentary in India in January, using emergency powers under the country’s Information Technology Rules. On July 31, communal violence broke out in Nuh district in Haryana state during a Hindu procession and swiftly spread to several adjoining districts. Following the violence, as part of a growing pattern, the authorities retaliated against Muslim residents by illegally demolishing hundreds of Muslim properties and detaining scores of Muslim boys and men.

The demolitions led the Punjab and Haryana High Court to ask the BJP-led state government whether it was conducting “ethnic cleansing.” Over 200 people were killed, tens of thousands displaced, hundreds of homes and churches destroyed, and the internet shut down for months, after violence erupted in May in Manipur state, in northeastern India, between the majority Meitei and the minority Kuki Zo communities. BJP’s state chief minister, N. Biren Singh, fueled divisiveness by stigmatizing the Kuki, alleging their involvement in drug trafficking, and providing sanctuary to refugees from Myanmar. In August, the Supreme Court said the state police had “lost control over the situation,” and ordered special teams to investigate the violence, including sexual violence. In September, over a dozen United Nations experts raised concerns over the ongoing violence and abuses in Manipur, saying the government’s response had been slow and inadequate.

Indian authorities continued to restrict free expression, peaceful assembly, and other rights in Jammu and Kashmir. Reports of extrajudicial killings by security forces there continued throughout the year. The government attempted to shield a BJP parliament member, Brij Bhushan Singh, after female athletes filed complaints of sexual abuse spanning a decade, when he was president of the Wrestling Federation of India. Security forces tackled and forcibly detained women wrestlers, including Olympic medalists, as they demanded justice and safety for female athletes. In September, India, holding the rotating presidency, hosted the summit of the Group of Twenty (G20), the world’s largest economies, and pushed to include the African Union as a permanent member and make the group more representative and inclusive. India actively promoted the use of a digital public infrastructure toexpand delivery of social and economic services. However, rampant internet shutdowns, lack of privacy and data protection, and uneven access among rural communities harmed those efforts.

AHEAD OF INDIA ELECTION, TENSION BREWS IN KASHMIR OVER TRIBAL CASTE QUOTAS

Tral, Indian-administered Kashmir – Like many people from his nomadic tribal community, Bashir Ahmed Gujjar, a 70-year-old shepherd, never went to school. Poor and often on the move, formal education was not an option. Things changed for the Gujjars, his community, after the government introduced quotas for what are known in India as Scheduled Tribes (STs), in state-run educational institutions and government jobs in 1991 as part of an affirmative action programme for historically marginalised groups. Gujjars were included in the beneficiaries. Families decided to send their children to school and college. “My children, my nieces and nephews have all been fortunate enough to have received education because of the ST status bestowed on us by the government,” Bashir told Al Jazeera at his home in the region’s Pulwama district.

He said his niece now works as a teacher in a government school in Tral because of the job quotas that Gujjars can avail. Now, he fears the next generation of his community could lose out on those gains of the past three decades. Earlier this month on February 6, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government passed a legal amendment to include another community, the Paharis, within the list of STs. At the time, federal Tribal Affairs Minister Arjun Munda said the law would not erode the education and job quotas currently available for existing tribes — but would add additional quotas for new communities.

But the government is yet to explain how it plans to do that, leading to fears among the Gujjars and Bakarwals, two major tribal communities originally covered by the affirmative action, that they will now need to split their benefits with the Paharis who have historically been seen as better off. “We have no hope for the future. The government is giving our share of guarantees to others,” Bashir said. The government move has sparked a wave of protests by Gujjar and Bakerwal community groups, demanding that the amendment be repealed. The move has also spawned caste divisions in a region already on the edge over other controversial moves by the Modi government in recent years. The decision to add Paharis to the list of STs could affect the national elections, expected to be held between March and May.

India’s Modi visits Kashmir: How has the region changed since 2019? Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Thursday made his first visit to Kashmir since his government’s controversial 2019 decision to scrap the region’s special semi-autonomous status. Addressing a crowd at a football stadium in the region’s largest city, Srinagar, Modi claimed that the removal of Article 370, which granted a measure of autonomy to Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir, had ushered in development and peace. “I am working hard to win your hearts, and my attempt to keepwinning your hearts will continue,” Modi said even as the region was placed under a security blanket, with thousands of soldiers and paramilitary forces deployed and new checkpoints set up. The 2019 decision was hailed by the Hindu nationalist movement that Modi represents, but was met with anger in Kashmir – one of India’s only two Muslim-majority regions – which has seen a decades- long armed rebellion against Indian rule.

Since then, Modi has visited Hindu-majority Jammu region, but has stayed away from Kashmir, until now, on the eve of the 2024 national elections. Modi and his government have claimed that the scrapping of Article 370, and their subsequent policies in Kashmir, have helped transform the region for the better. Here’s a look at key changes brought to Kashmir by Modi’s government since 2019: Special status under Article 370 removed Article 370, which was enshrined in India’s constitution signifying Kashmir’s unique relationship with New Delhi, granted the Himalayan region a large measure of autonomy: Kashmir had its own constitution and flag, it could make its own laws in all matters except finance, defence, foreign affairs and communications.

Until 1965, the Indian-administered region had its own prime minister under whom property and domicile laws were passed to protect the interests and territorial rights of the region’s Indigenous people. Indian-administrated Kashmir bifurcated into two Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir was bifurcated into two regions – Jammu and Kashmir in the west and Ladakh in the east. Neither region has statehood any more, as a consequence of the Modi government’s 2019 decisions. Both are governed directly from New Delhi. But people have expressed their grievances against their lack of democratic rights, with Ladakh too seeing frequent protests for more political rights and authority in local governance.

No elections for state legislature There have also been elections to fill seats in the village councils, also called panchayat, and municipal bodies, but they have very limited power, with the region ruled by New Delhi’s representative and bureaucrats. India’s Supreme Court in December ordered the government to hold local elections by September 30, 2024. Kashmir’s pro-India political parties have been demanding that elections be held in the region. Modi and his government, however, have not indicated when they will hold the elections.

Clampdown on free speech