Humman Rights Report

Humman Rights Report

INTRODUCTION

As of August 5, 2023, it has been four years since the fundamental human rights of the people in Indian occupied Kashmir were stripped away, coinciding with the end of a seven-decade-long special status under Article 370, as the Modi administration charted a new course.

The Modi regime’s actions stand in clear defiance of fundamental human rights and humanitarian principles, disregarding not only the thirteen United Nations Security Council resolutions on Jammu & Kashmir, but also the very essence of international consensus.

The BJP’s determined implementation of “settler colonialism” is primarily directed at reconfiguring demography and land ownership patterns, thereby significantly affecting the livelihoods of Kashmiri residents.

A pivotal juncture was reached on August 2, 2023, as India’s Supreme Court began hearing of a cluster of petitions, which rigorously contest the constitutional validity of the BJP’s seminal 2019 maneuver.

However, during these ongoing legal proceedings, a common sentiment emerges from the IoK, marked by a sense of doubt and lack of optimism, because of India’s historical non-compliance with international humanitarian laws and its track record of human rights violations in Kashmir.

NEW AMENDMENTS

Following the Indian government’s decision to abrogate Article 370, a series of unjust laws have enforced in Indian occupied Jammu & Kashmir. Around 890 new central laws and 130 state laws have been extended to the region. One noteworthy shift was the replacement of the J&K State Human Rights Commission (JKSHRC) with the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), thereby eliminating the distinct human rights commission that was previously established for the region. This move contradicts the recommendations of the J&K Law Commission, which had suggested the creation of a separate entity for safeguarding rights. Another change involved the repeal of the J&K Right to Information (RTI) Act, 2009, after the abrogation of Article 370. Furthermore, the dissolution of the State Commission for Protection of Women and Child Rights by the central administration in New Delhi is noteworthy, particularly considering the prominence of women’s rights discussions in relation to Article 35A.

The Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Act of 2019 led to the dissolution of seven commissions and the repeal of around 200 protective laws by the Indian government. The Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Orders of 2020 have repealed 12 Acts and amended 14 land-related laws in the region. Not a single law passed in the last four years has had inputs from the Kashmiri population whose lives these laws are meant to radically alter.

STRUGGLING ECONOMY

Indian occupied Jammu and Kashmir has encountered significant economic challenges, experiencing an estimated loss of approximately $2.81 billion and over 496,000 job reductions in sectors such as handicrafts, tourism, and information technology in just a span of five months following the events of August 5th. The statistics are telling: investments have plummeted by 55 percent over the course of the last four years. For the fiscal year 2021-22, total investment in Jammu and Kashmir amounted to $46 million, marking a decrease from the previous year’s $50.5 million and a stark contrast to the $102.8 million invested in 2017-18.

In the financial year 2021-22, investments were $46 million, down from $50.5 million the year before, and a significant fall from the $102.8 million invested in 2017-18. Importantly, the biggest drop in investments occurred even before the COVID-19 pandemic, with the amount invested decreasing by half from $72.3 million in 2018-19 to $36.3 million in 2019-20.

NEW DOMICILE LAW

Under Article 370, outsiders were prohibited from permanently settling or purchasing property in Indian administered Kashmir. Nevertheless, a domicile law introduced in 2020 allows individuals who have resided in the region for 15 years or have completed seven years of education there to apply for a domicile certificate. This certificate grants them the right to seek land and employment opportunities.

Approximately 5 million domicile certificates have been granted in J&K. The local government, acting under the directives of New Delhi, has conveyed the possibility of imposing a penalty of Rs 50,000 ($660) on officials failing to issue a domicile certificate within the prescribed 14-day period. This timeframe, however, is seen as challenging for properly verifying applicants’ claims.

LAND OWNERSHIP

The startling numbers indicate a rise in interest from outsiders, as property purchases by non-local individuals went up from just one in 2020 to 127 in 2022. This increase raises questions about the makeup of the local population and how the demography of the region is changing.

The Indian government has specifically targeted ancestral agricultural and non-agricultural lands for its settlement and development efforts. They have set aside 178,005.213 acres of land in Kashmir and 25,159.56 acres in Jammu for these projects. A substantial 70 hectares of land have been marked as strategic areas for use by the Indian armed forces.

Administrative decisions also included amendments to the Control of Building Operations Act, 1988, and the J&K Development Act, 1970.

The Jammu and Kashmir administration has given approval to designate over a thousand kanals of land in Gulmarg and 354 kanals in Sonamarg as “strategic areas.” This land, totaling 178,005.213 acres in the Kashmir region and 25,159.56 acres in Jammu, was taken by Indian authorities without any prior notice to the rightful owners.

The Revenue department’s list of ‘State land,’ spanning 11,737 pages across 20 districts of IIOJK, is primarily owned by Kashmiris under various Acts and orders passed by the previous state government in favor of landless peasants.

A policy proposal suggests providing five marlas of land (about 0.031 acres) and building houses under the Prime Minister Housing Scheme-Rural, a government initiative to offer housing to impoverished rural residents.

The federal rural development ministry has set a goal of constructing 199,550 new houses in the region for the financial year 2023-24. These homes are intended for economically weaker sections (EWS) and low-income groups in the area, including urban migrants like laborers, street vendors, and rickshaw pullers. Any Indian citizen who has temporarily or permanently migrated for work, education, or an extended tourist visit is also eligible, as stated by the Jammu and Kashmir Housing Board.

The Union Territory has seen an influx of investments from both Indian and multinational corporations, with a total of 1,559 companies investing in Jammu and Kashmir. This represents a significant increase from 310 entities in the 2020-2021 financial year to 1,074 entities in 2022-2023. As the region undergoes changes, it is vital to consider how these shifts are affecting the local population and their way of life.

CRACKDOWN ON GOVERNMENT EMPLOYS

In April 2021, the local government established a special task force to review cases of employees suspected of engaging in activities that could warrant action under Article 311. This legal provision pertains to the potential dismissal, removal, or reduction in rank of individuals employed in civil roles within the Union or a State, following an inquiry. Since 2019, over 50 government employees in Indian-administered Kashmir have been dismissed from their positions based on unclear allegations of posing a “threat” to the state’s security.

The law used for these terminations allows the government to terminate employees without providing an explanation. Out of the 66 senior bureaucrats serving in the region, 38 are individuals from other Indian states. Many other non-locals hold positions in various central government institutions such as banks, post offices, telecommunication facilities, security organizations, and universities.

CULTURAL INVASION

The Narendra Modi government has been changing names of historical places and institutions, part of its efforts to reshape the political history of Jammu and Kashmir.

On January 30, 2023, the Jammu and Kashmir government approved the naming of 57 infrastructure assets, like schools, roads, bridges, and sports stadiums, after the Indian army. This renaming of schools, colleges, roads, and buildings in Jammu and Kashmir is similar to what the BJP has been doing in the rest of India since 2014, aiming to erase Mughal influences.

For instance, in October 2019, the Chenani-Nashri Tunnel became the Dr. Shyama Prasad Mookerjee Tunnel. The Public Health Engineering, Irrigation and Flood Control Department was changed to the Jal Shakti Department. The Sher-e-Kashmir police medals for gallantry and meritorious service were renamed the Jammu and Kashmir police medals for the same, as of January 26, 2020.

In July 2021, the Divisional Commissioner’s office in Jammu instructed Deputy Commissioners to identify government schools in villages and municipal wards that could be named after the Indian Army, Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), and the police.

More changes are on the horizon, including renaming the Government College for Women, Srinagar, after Prof Riyaz Punjabi, and the Boy’s Higher Secondary School Jawahar Nagar after Prof Hamidi Kashmiri. The Government Degree College, Hyderpora, is proposed to be named after Padma Shri awardee Moti Lal Keemu, and Lal Mandi Road might be named after Sahitya Academy awardee poet Zinda Koul, or Masterji.

JK ADHAR/FAMILY CARD

The Modi government has launched a ‘unique family ID database,’ aiming to gather personal information of citizens. This database would include details about every family member in the area, such as their names, ages, educational background, employment status, and marital status, among other particulars.

Interestingly, there is already an Aadhar-linked system for direct beneficiary transfers. However, this move is seen as an additional surveillance measure adopted by the Jammu and Kashmir government. Back in 2018, India’s extensive Aadhar database suffered a reported breach that impacted over a billion ID

PROPERTY VANDALISM

The actions of the State Investigative Agency, involving the confiscation and destruction of personal property like homes and valuable belongings, result in a form of collective punishment affecting the people of Kashmir. Since 1989, more than 110,498 private properties have been demolished in IOK. Notably, there were 657 homes set ablaze in 2020, followed by 130 in 2021, and 196 in 2022.

holders. According to a report from Surfshark VPN, a cybersecurity firm based in the Netherlands, India ranked sixth among countries susceptible to digital attacks. The potential exposure of sensitive personal information in a region affected by conflict, particularly in the absence of a national data protection law, raises significant concerns about data security.

NEW EDUCATION POLICY

The recently introduced education policy of 2022-2023 appears to be aimed at reshaping the narrative of Kashmir’s history and potentially diminishing the Muslim identity associated with the region. This policy raises concerns about the potential impact on the cultural and historical heritage of Kashmir, as well as the preservation of its diverse identity

NEW LANGUAGE POLICY

The region’s population predominantly speaks several languages, with Kashmiri being the most common at 53%, followed by Dogri at 20%, Gujjar at 9.1%, Pahari at 7.8%, Hindi at 2.4%, and Punjabi at 1.8%. However, a significant development occurred in September 2020 when the Indian parliament enacted The Jammu and Kashmir Official Languages Act, 2020. This legislation added Kashmiri, Dogri, and Hindi to the list of official languages in Indian-occupied Kashmir (IOK). The announcement sparked intense reactions from Kashmiris and swiftly escalated conflicts centered around language matters within the region.

The creation of a language policy necessitates a comprehensive consideration of diverse factors, including historical, political, societal, religious, and national elements, as well as the practical needs of the population.

MEDIA POLICY 2020 AND CRACKDOWN ON JOURNALISTS

Journalists reporting from Kashmir have always faced great challenges, including intimidation, physical attacks, and arrests. In May 2020, the Jammu and Kashmir Department of Information and Public Relations (DIPR) introduced a revised Media Policy 2020. This policy aims to control the information shared in Kashmir, making media a tool for the government’s intended news and preventing the spread of “fake” news and activities seen as “anti-national.”

Local journalists are vital sources of information about the region, but they often experience harassment and intimidation, which have become common, unfortunately. Some journalists like Asif Sultan, Manan Gulzar Dar, Fahad Shah, and Sajad Gul are facing unjust detentions under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) and Public Security Act (PSA) for their writings about the ground situation.

In October 2022, Kashmiri woman journalist Sanna Irshad Mattoo was stopped from traveling to New York to receive her Pulitzer Prize during the Pulitzer Prize event. Despite having a valid visa and ticket, she was prevented from boarding her flight at New Delhi’s IGI Airport. This incident marked the second time she was stopped by Indian authorities from traveling abroad. In an earlier instance in 2022, she was prevented from traveling to France to accept a grant she had been awarded.

The number of foreign correspondents in Kashmir has significantly decreased due to a media policy implemented in June 2020, which required background checks for journalists. To further tighten control, the Modi government issued an order in September 2021, mandating that “unauthorized” journalists obtain approval before performing their jobs.

DELIMITATION PROCESS

On May 5, a commission appointed by the government introduced a delimitation plan outlining 90 assembly constituencies for the former state of Jammu and Kashmir, excluding Ladakh. Among these, 43 seats were designated for Jammu, while 47 were allocated for Kashmir. Previously, Jammu held 37 seats and the Kashmir valley had 46. The delimitation commission placed considerable emphasis on factors like “geographical area and

accessibility” when crafting electoral maps for the Himalayan region. By analyzing the commission’s December 20 statement, it becomes evident that an average assembly seat in the Kashmir valley would represent around 146,000 people, while in Jammu, a constituency might encompass an average of 125,000 residents.

The proposed reallocation of assembly seats seems heavily skewed in favor of Jammu, potentially leading to a political shift where Muslims could become a minority in India’s sole Muslim-majority area. In the previous assembly elections held in 2014 in Indian-administered Kashmir, the Hindu nationalist BJP secured 25 out of 37 seats in the Jammu region, while failing to secure any seats in the valley.

Over the past seven decades, all chief ministers in Indian-administered Kashmir have been of Muslim faith. Nevertheless, the right-wing BJP has long promised its supporters in the Muslim-majority region the appointment of a Hindu chief minister. These proposals as being imbued with the ideological leanings of the BJP. The party has expedited the delimitation process in the region, in contrast to the freeze imposed in the rest of India until 2026.

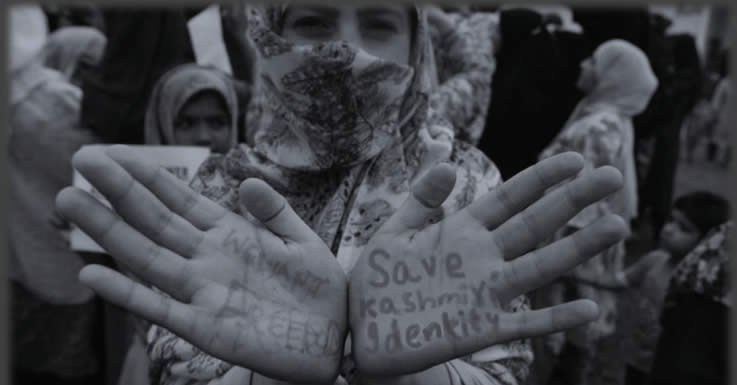

HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS

The Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir has been facing a complex struggle. Kashmiri people are fighting for their rights and freedom against India’s strong military presence and control. During the months from June 23 – August 23, Indian forces in the area have caused a lot of suffering and damage. The facts show a worrying picture – there were 67 reported killings. Also, they arrested 130 people, showing they are cracking down on regular people.

The violence didn’t spare even the vulnerable – 75 people got injured because of the Indian forces’ actions. They also did 82 siege and search operations, adding to the feeling of fear and uncertainty.

The impact of this conflict is more than just loss of life and harm. 34 cases of property damage were recorded, making things worse for Kashmiri people. In response, authorities cut off the internet 92 times, which stopped people from communicating and getting important information.

Sadly, over 8 women became widows and 11 children lost their parents, showing how families and society are deeply affected.

These numbers remind us of the ongoing human rights violations and the suffering caused by the Indian forces in this region. The world should keep a close watch on this situation and work towards a peaceful solution that respects the basic rights and dignity of the people in Kashmir.

Related Reports