The State of No Story

The State of No Story

INTRODUCTION

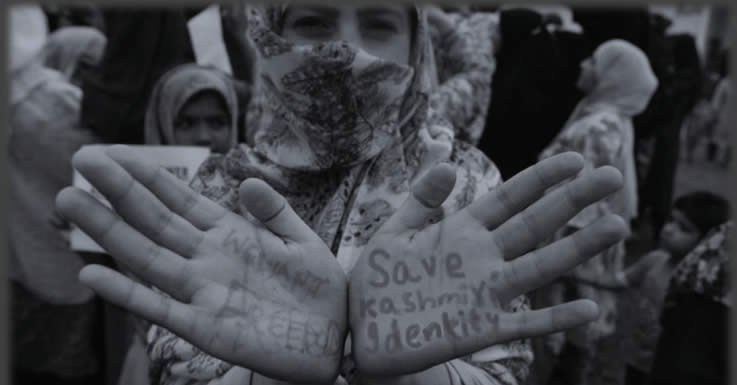

Freedom of expression is the foundation of democracy. It enables citizens to question power, demand accountability and contribute to public life. India’s Constitution guarantees this freedom under Article 19(1)(a), affirming the right to speak, publish and dissent. At the international level, India has pledged to uphold these same principles through its ratification of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Articles 19 and 21 of the Covenant protect the right to expression, peaceful assembly and access to information. These are not abstract ideals but legal and moral commitments that define democratic legitimacy. Yet, in practice, these protections have been steadily eroded, most visibly in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K).

Since the abrogation of Article 370 in August 2019, the region has become a laboratory for state-controlled information management. The constitutional changes were accompanied by a communications blackout, the longest ever imposed in a democracy. This blackout was not only a security measure; it was a political statement. It signaled the beginning of a new order in which truth itself would be regulated, mediated and often silenced. Journalism in Kashmir now functions under siege. The act of reporting has become an act of resistance. Newsrooms are routinely raided, editors questioned and reporters detained. Counterterrorism and preventive detention laws, such as the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) and the Public Safety Act (PSA) are selectively deployed to criminalize journalists. These laws blur the line between journalism and subversion.

By labeling reporting as “anti-national” or “terror-linked,” the state reframes truth-telling as a threat to sovereignty. The arbitrary application of these laws has created an environment of constant fear, forcing journalists to choose between silence and persecution. The erosion of press freedom is not accidental; it is systematic. Legal frameworks, administrative controls and digital surveillance work together to suppress dissenting voices. The new Media Policy introduced in 2020 institutionalized censorship by granting government officials the power to determine what constitutes “fake news” or “anti-national content.”

This effectively transforms public information departments into instruments of propaganda. Journalists in Kashmir now operate in a shrinking space, where every article, image, or tweet can be construed as sedition. The consequences are both professional and psychological. Independent journalists face travel bans, confiscation of equipment and denial of accreditation. Many have been forced to abandon their profession or relocate. News organizations are crippled by the withdrawal of government advertising, their primary source of revenue. This economic strangulation complements the legal and administrative repression, ensuring that compliance is not just expected, it is enforced. The once vibrant local press, which provided a counter-narrative to state narratives, now survives only in fragments.

This systematic silencing has broader socio-political consequences. Censorship breeds alienation. When local voices are muted, the collective memory and lived experiences of a people are erased from public discourse. The fear of reprisal has created a generation of self-censoring journalists. The loss is not only theirs, it is Kashmir’s and it is the world’s. Without a free press, the suffering of ordinary citizens remains undocumented and the global community is deprived of credible, firsthand accounts of human rights violations.

Internationally, this crisis has drawn growing concern. Reports by the United Nations, Amnesty International, the Committee to Protect Journalists and Reporters Without Borders have repeatedly highlighted India’s misuse of security laws to intimidate journalists. India’s ranking in global press freedom indices has sharply declined, reflecting the deepening hostility toward independent media. Yet, despite international scrutiny, accountability remains elusive. India continues to frame its repression as a domestic issue, shielded by narratives of counterterrorism and national integrity.

This research, therefore, seeks to unravel how state power, under the guise of security, is weaponized to silence truth in Kashmir. It asks three core questions. First, how do India’s security frameworks criminalize journalism in the region? Second, what are the social and political costs of this prolonged intimidation? And third, how does the international community interpret India’s accountability within the global human rights system? Together, these questions reveal the anatomy of a controlled narrative, a system in which speech is monitored, truth is negotiated and silence becomes the safest language.

In the post-2019 order, journalism in Kashmir is no longer a profession; it is an act of endurance. The shrinking space for truth reflects the shrinking space for democracy itself. The press, once the voice of The Strategic Erasure of Independent Journalism in Jammu & Kashmir5 the people, now stands at the intersection of fear and defiance. What unfolds in Kashmir is not merely a local crisis but a global warning, of how quickly democratic frameworks can be dismantled when the right to speak freely is treated as a crime.

Research Rationale

The present study examines the systematic erosion of press freedom in Jammu and Kashmir as both a political strategy and a human rights crisis. It argues that the state’s suppression of journalism is not incidental but structural, embedded in the legal, administrative and economic mechanisms of governance. In Kashmir, truth-telling has been transformed into a punishable act, while silence has become the precondition for survival.

The rationale behind this research lies in understanding how journalism, once a space for public debate, has been absorbed into the state’s security apparatus. The control of information serves a dual function: it neutralizes dissent at the local level and manages international perception by projecting an image of normalcy. The Media Policy of 2020 institutionalized this control by empowering bureaucrats to decide what qualifies as “fake,” “anti-national,” or “seditious” reporting. Through selective disbursal of government advertisements and accreditation, the state has created an economic chokehold on independent media. At the same time, digital surveillance and social media monitoring have blurred the line between journalism and activism. Online posts, photographs, or interviews that challenge official narratives are now grounds for detention under counterterrorism laws. The chilling effect of these measures extends beyond journalists to the entire civil society, reinforcing a culture of fear and self-censorship.

Methodology

The study adopts a qualitative and analytical approach rooted in media studies, human rights law and political analysis. It draws upon primary and secondary sources, including court judgments, verified news reports and investigative documentation from organizations such as Amnesty International, Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Free Speech Collective and Human Rights Watch. The research also relies on case-based analysis of individual journalists such as Fahad Shah, Aasif Sultan, Sajad Gul and Irfan Mehraj whose experiences illustrate the structural nature of repression. Their cases are examined not merely as isolated incidents but as indicators of a deliberate pattern of criminalization.

Furthermore, the study engages with international human rights instruments—the ICCPR, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the UN Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists to assess India’s compliance with global norms. By cross-comparing the situation in Kashmir with other conflict zones such as Palestine and Myanmar, it situates Kashmir’s experience within the broader framework of “mediatized authoritarianism,” a governance model where control over information becomes central to sustaining occupation and political legitimacy.

Significance and Thematic Focus

The significance of this study lies in its attempt to reclaim journalism as an act of truth-telling in an environment where truth has been systematically suffocated. It highlights how press freedom is not merely a professional issue but a measure of democratic health and human rights protection. In Jammu and Kashmir, the suppression of journalism is inseparable from the suppression of political agency itself. By tracing the transformation of the media landscape, through legal instruments, economic dependency and digital coercion, this research lays the foundation for understanding the broader collapse of civic space in the region.

It further examines how journalists are detained under preventive laws, how media policies institutionalize censorship and how fear has redefined professional ethics in the Valley. The crisis of journalism in Jammu and Kashmir must be understood within the larger narrative of democratic regression and systematic human rights denial. The vanishing space for truth in the Valley is not only a local tragedy but a global warning, a reminder that when a state criminalizes journalism, it begins to criminalize democracy itself.

MEDIA TRANSFORMATION POST–2019

The Restructuring of Jammu & Kashmir The year 2019 marked a decisive rupture in the political and constitutional history of Jammu & Kashmir. On 5August 2019, the Government of India abrogated Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, dissolving the region’s special status and autonomy (Amnesty International, 2020). The move also revoked Article 35A, which had defined permanent residency and local rights over land and employment. Together, these constitutional provisions had symbolised a federal accommodation between India and Jammu & Kashmir since 1949. Their removal was neither consultative nor consensual. It was imposed through a Presidential Order and parliamentary enactment in the absence of an elected state legislature (Al Jazeera, 2024).

The abrogation effectively dissolved the state’s limited autonomy. The region was reorganised into two Union Territories, Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh, under the Jammu & Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019. This restructuring was more than administrative. It represented the consolidation of central authority through direct rule. The decision placed the region under the command of the Lieutenant Governor, an appointee of the central government, bypassing local institutions entirely (Free Speech Collective, 2025).

The shift to a Union Territory model transformed governance into a bureaucratic, security-driven enterprise. Decision-making migrated from Srinagarm to Delhi. Policies on land, employment, education and media were now dictated by central ministries rather than elected local representatives. This arrangement blurred the distinction between governance and occupation. The civil administration became an extension of security institutions, operating under counter-insurgency logic rather than civilian rule (Amnesty International, 2020). Simultaneously, an unprecedented communications blackout was enforced. Internet, mobile networks and landline services were suspended, isolating the region from the world. The blockade, which began in August 2019, continued in varying intensities until early 2021, making it the longest internet shutdown in a democratic country (Reporters Without Borders [RSF], 2019).

The blackout silenced journalists, academics and civil society alike. For months, newspapers could not publish and digital outlets shuttered. Only government-sanctioned information flowed through official channels (Press Council of India, 2022). The communications lockdown was accompanied by mass detentions of political leaders, activists and journalists. Former chief ministers, opposition legislators and human rights defenders were placed under preventive detention. The government justified these actions as necessary for law and order, yet they signalled a deeper project — the systematic dismantling of dissent (Al Jazeera, 2024). In the name of stability, the state erased political plurality.

This restructuring redefined the social contract between the Indian State and the people of Jammu & Kashmir. The promise of constitutional rights was replaced by administrative decrees. Where once limited self-rule existed, an unaccountable bureaucratic regime emerged. The central government’s control extended not only to territorial governance but also to narrative production. Information itself became a tool of governance (Free Speech Collective, 2025). The post-2019 transformation thus laid the foundation for the suppression of media freedom. By concentrating power in the hands of the Union government and its security apparatus, the state ensured that information about Kashmir could be curated, filtered or suppressed.

The blackout was not merely a security measure, it was the first phase of a larger architecture of information control that would later be institutionalised through new laws, policies and media frameworks (Kashmir Life, 2022). From Elected Representation to Controlled Governance Following the abrogation of Article 370, Jammu & Kashmir entered a prolonged phase of political dormancy. The state assembly, dissolved in 2018, was not restored. Instead, the Lieutenant Governor and a set of bureaucratic advisors assumed control over policy- making. This arrangement marginalised local political actors and undermined representative governance (Amnesty International, 2020).

Even after limited political activity was permitted, the scope of local decision-making remained symbolic. Political parties such as the National Conference and the Peoples Democratic Party, once central to the democratic process, found themselves constrained by the new administrative order. The detention of their leaders, including Farooq Abdullah, Omar Abdullah and Mehbooba Mufti, underscored the erosion of political legitimacy. When released, their participation was limited to heavily regulated engagements under central supervision (Al Jazeera, 2024).

The new political architecture replaced electoral accountability with bureaucratic dominance. The Lieutenant Governor’s office, supported by the Home Ministry and security agencies, became the focal point of all administrative authority. Decisions concerning land reforms, domicile laws and media regulation were issued unilaterally, often without public consultation. This bureaucratization created a governance structure The Strategic Erasure of Independent Journalism in Jammu & Kashmir7 insulated from local criticism and resistant to transparency (Free Speech Collective, 2025). The reconfiguration also redefined the relationship between the state and its citizens. Civilian oversight disappeared and the security establishment gained unprecedented influence. Policing became the primary mode of governance. Surveillance systems were expanded, checkpoints multiplied and digital monitoring became routine.

Civil servants operated under the dual pressure of bureaucratic loyalty and security vetting. This produced a culture of compliance and silence, within government institutions and among the wider population (Kashmir Life, 2022). The erosion of representative institutions had direct implications for the media. In the absence of an independent legislature or local accountability mechanisms, the press lost its traditional interlocutors. Journalists could no longer rely on elected officials for information or verification. The state’s narrative was mediated through bureaucrats and police spokespersons, leaving little room for contestation. Press briefings were replaced by official hand-outs and dissenting voices were systematically marginalised (Al Jazeera, 2024).

This centralisation of authority also reconfigured the flow of public information. The government increasingly relied on controlled media releases to project a narrative of normalcy. These statements portrayed development, tourism and peace, while omitting references to detentions, protests or violence. The lack of representative governance meant there was no institutional challenge to these narratives. Media houses that deviated from the official line faced economic retaliation or legal intimidation (Free Speech Collective, 2025).

The brief experiment with elected representation after 2019, under the Lieutenant Governor’s supervision, exposed the limitations of the new order. Local bodies and district development councils were established but with minimal powers. Their budgets, staffing and policies remained under the control of central ministries. Even routine administrative decisions required approval from the Lieutenant Governor’s office. These bodies functioned more as instruments of political optics than of democratic empowerment (Amnesty International, 2020).

This controlled governance model ensured that the political space remained constricted. Public participation in policymaking was replaced by bureaucratic announcements. Dialogue was substituted with directives. Within this context, the press became both a witness and a casualty of democratic retreat. Journalists were expected to amplify official narratives of “peace and progress” rather than question their authenticity (Talk in Kashmir Life, 2022).

The fusion of political and administrative control also reshaped the socio-political psyche of the region.Citizens, accustomed to contesting authority through electoral and civil channels, now encountered an unresponsive system governed by decree. This alienation deepened the disconnect between the state and society, reinforcing the perception that democracy in Kashmir was performative rather than participatory (Free Speech Collective, 2025). The 2020 Media Policy: Institutionalizing Censorship

The culmination of post-2019 information control was the introduction of the Jammu & Kashmir Media Policy 2020. Issued by the Department of Information and Public Relations (DIPR), the policy was framed as a mechanism to “foster a positive image of the government” and “curb misuse of media” (Maktoob Media, 2024). In reality, it codified censorship. The policy granted government officials sweeping powers to determine what constitutes “fake news”, “anti-national content”, or “unethical reporting.” These categories were left deliberately vague, allowing for arbitrary interpretation. The DIPR, in coordination with security agencies, was authorised to vet content across print, electronic and digital platforms. Media outlets found in violation could face suspension of accreditation, withdrawal of government advertisements, or legal action under national security laws (Maktoob Media, 2024).

This framework institutionalised prior informal controls. Before 2020, journalists already faced police questioning and temporary detentions. After the policy’s enactment, such practices gained bureaucratic legitimacy. The state no longer needed to rely solely on intimidation; it now possessed a legal architecture to regulate speech. Every newsroom in Kashmir became subject to surveillance and scrutiny (Free Speech Collective, 2025).

The policy also linked financial viability to editorial loyalty. Government advertising, historically the primary source of revenue for local newspapers, was made contingent on “positive coverage”. Outlets critical of government actions faced immediate withdrawal of advertisements. Many small and independent publications were forced to shut down or scale back operations. This economic dependency became an effective mechanism of control (Maktoob Media, 2024).

The DIPR’s monitoring mechanisms extended to social media. Journalists’ personal accounts were routinely observed and posts critical of the government were flagged for investigation. The introduction of the new Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines) Rules, 2021 further expanded state surveillance and liability for online platforms. These rules required digital platforms to trace the origin of messages and remove content deemed unlawful. Together, these measures created an environment where expression was conditional upon obedience (Free Speech Collective, 2025). The 2020 Media Policy also altered the relationship between journalists and the public. Reporters began self-censoring, aware that any deviation from official narratives could trigger punitive action. Investigative journalism virtually disappeared. Coverage of protests, human rights abuses, or political dissent was replaced by stories on development schemes and tourism.

The shift was not merely editorial but existential—the survival of media organisations now depended on compliance (Maktoob Media, 2024). Institutionalised censorship also had profound implications for truth and accountability. By monopolising information, the state controlled the narrative of conflict and governance. Reports of enforced disappearances, arbitrary detentions and civilian killings were either under-reported or omitted. International media access was heavily restricted, ensuring that the world saw only curated images of calm and progress (Amnesty International, 2020).

This policy-driven transformation aligns with a broader national trend of shrinking press freedom in India. However, in Jammu & Kashmir, the stakes are higher. Here, media control intersects with military occupation and political disenfranchisement. The press is not only censored but also criminalised. The policy effectively redefines journalism as a potential threat to national integrity, equating dissent with disloyalty (Al Jazeera, 2024).

The cumulative effect of these developments is the near- collapse of independent media in Kashmir. Traditional newspapers such as Greater Kashmir and Rising Kashmir have curtailed critical reporting. Digital outlets face constant takedown notices and intimidation. Freelance journalists, particularly women, encounter harassment and travel restrictions. The space for factual reporting has narrowed to a degree unseen in previous decades (Kashmir Times, 2025).

What began in 2019 as a constitutional restructuring has evolved into a comprehensive regime of narrative management. The 2020 Media Policy did not emerge in isolation; it completed a trajectory that began with the abrogation of Article 370. The blackout silenced voices. The bureaucratic regime centralised control. The policy institutionalised censorship. Together, these measures transformed Kashmir’s information ecosystem into a state-managed apparatus where truth is filtered through political imperatives (Kashmir Life, 2022).

THE CRIMINALIZATION OF JOURNALISM

Instruments of Repression In Jammu and Kashmir, journalism has been transformed from a profession of truth-seeking into a high-risk activity defined by fear and uncertainty. The state has weaponized law, policy and technology to suppress dissent and discipline independent voices. The most potent instruments of this repression are the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), the Public Safety Act (PSA) and an ever-expanding surveillance regime that fuses digital monitoring with physical intimidation (Kashmir Times, 2025; Al Jazeera, 2023).

The UAPA lies at the core of India’s national security architecture. In Kashmir, it has evolved into a tool for silencing journalists. Its vague and expansive definitions of “unlawful activity” and “terrorist act” give authorities unchecked power to interpret reporting as an act of subversion (Al Jazeera, 2024; RSF, 2025). Journalists can be accused of “spreading disaffection,” “inciting disloyalty,” or “supporting terrorism” merely for questioning official narratives or publishing eyewitness accounts that contradict state versions of events (Kashmir Times, 2025). Once charged under the UAPA, pre-trial detention can last for years, as the law reverses the presumption of innocence (Front Line Defenders, 2024; Article14, 2024). Bail becomes nearly impossible and trials drag on indefinitely. This process itself becomes punishment (Guardian, 2023).

Through the UAPA, the Indian state has effectively equated the act of reporting in Kashmir with a threat to sovereignty. This legal manipulation not only The Strategic Erasure of Independent Journalism in Jammu & Kashmir9 criminalizes journalism but also redefines it as an anti- state activity. By collapsing the line between journalism and terrorism, the state erases the legitimacy of press freedom. The consequences are far-reaching: newsrooms self-censor, editors withdraw critical content and the public loses access to independent information (RSF, 2025; Kashmir Times, 2025). The PSA complements this system by enabling what has been described as “revolving-door arrests.”

Under the PSA, individuals can be detained for up to two years without trial (Newslaundry, 2024). Even when courts quash detention orders, journalists are often rearrested under new dossiers within days (IFJ, 2022). This endless cycle of release and re-arrest ensures that a journalist remains under constant threat. The law’s preventive nature allows authorities to imprison individuals not for what they have done, but for what they might do. This speculative logic destroys the basic premise of justice (Kashmir Times, 2025). In Kashmir, the PSA serves not as a preventive measure but as an instrument of control. It targets not only journalists but also activists, academics and ordinary citizens who express dissenting opinions (Kashmir Times, 2025). The vagueness of its language—phrases like “acting in a manner prejudicial to public order”— gives security agencies almost limitless discretion. The effect is chilling: those detained lose not just their liberty but their livelihoods, reputations and psychological well- being (RSF, 2025). Many return to their work fearful and restrained, while others abandon journalism altogether.

Alongside these legal tools, the use of surveillance, raids and digital profiling has institutionalized fear. Journalists’ phones are tapped, their emails monitored and their online activities scrutinized (Kashmir Times, 2025). Security agencies summon reporters for “background checks” or “informal questioning” designed to intimidate rather than investigate (Al Jazeera, 2023). Homes are raided at night, equipment is confiscated and social media posts are dissected for signs of “anti-national sentiment” (Front Line Defenders, 2024).

This surveillance infrastructure is reinforced by new technologies that track digital footprints. Facial recognition systems, Pegasus-type spyware and metadata analysis are employed to build profiles of journalists and their networks. These tools, originally intended for counter-terrorism, have been redirected toward information control (Al Jazeera, 2023). The result is a climate of perpetual suspicion. Every conversation feels monitored, every article carries risk and every interaction with sources becomes an act of courage.

The combination of the UAPA, PSA and digital

surveillance represents a layered system of repression. Each law and mechanism feeds into the other, ensuring that journalists are trapped in a web of legal vulnerability and psychological pressure. Together, they create a landscape where truth is criminalized and silence becomes a survival strategy (Kashmir Times, 2025; RSF, 2025). Case Studies of Journalistic PersecutionThe abstract machinery of repression becomes most visible through the experiences of individual journalists. In Jammu & Kashmir, several reporters have become emblematic of the state’s campaign against free expression. Their stories reveal how laws meant to safeguard the nation are weaponized to suppress it.

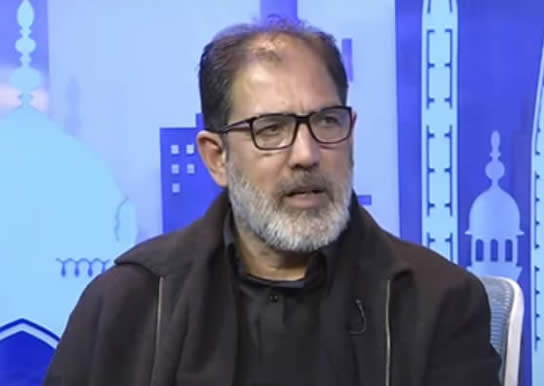

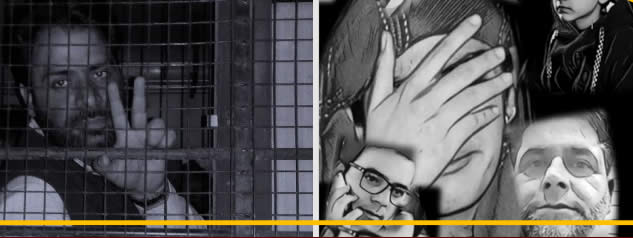

Fahad Shah, the editor of The Kashmir Walla, symbolizes the struggle of Kashmir’s independent press. Known for his measured reporting and commitment to balanced journalism, he was arrested multiple times between 2022 and 2023. His publication had covered sensitive issues such as civilian killings, enforced disappearances and protests. Authorities accused him of “glorifying terrorism” and “spreading fake news.” Despite the lack of credible evidence, he was detained under both the UAPA and PSA (IFJ, 2022; Front Line Defenders, 2024). His newsroom was raided, his staff harassed and his website later blocked across India (Kashmir Times, 2025). His ordeal sent a clear message to other journalists: neutrality itself is now punishable.

Aasif Sultan, another journalist from Srinagar, was detained in 2018 for a story profiling a local militant commander. His work was purely journalistic, yet he spent nearly six years in prison. Even after a court ordered his release, he was immediately re-arrested under the PSA (Article14, 2024; Front Line Defenders, 2024). His repeated incarcerations illustrate how preventive detention functions as punishment by repetition, undermining judicial authority and silencing critical reporting through exhaustion (RSF, 2025). Sajad Gul, a young trainee reporter, was arrested in 2022 after uploading a video showing a family protesting against a civilian killing. Authorities deemed his coverage “anti-national propaganda.” He was detained under the PSA despite court orders for his release (Front Line Defenders, 2024). His case exemplifies the vulnerability of early-career journalists who lack institutional protection. For them, a single article can lead to imprisonment or a lifetime ban from the profession.

Irfan Mehraj, an independent journalist known for documenting human rights abuses, was arrested in 2023 under the UAPA (Al Jazeera, 2023). His detention marked a turning point in the criminalization of human- rights journalism. By targeting those who investigate enforced disappearances and torture, the state signaled that even factual documentation of violations could be branded as “terror support” (Kashmir Times, 2025). Majid Hyderi, a veteran journalist and TV commentator, was detained under the PSA in 2023. The official dossier cited his social-media posts and televised debates as grounds for arrest. The vagueness of these charges illustrates how personal opinion and professional commentary are conflated with threats to public order (Kashmir Times, 2025).

Each of these cases follows a similar trajectory, surveillance, intimidation, arrest and silencing. The process inflicts profound psychological damage. Journalists describe sleepless nights, trauma from interrogation and fear for their families. Many have lost their jobs as employers distance themselves from those labeled “security risks” (RSF, 2025). The result is a decimated press corps operating under a regime of uncertainty. Beyond Kashmir, journalists across India face parallel forms of repression, though often without the same intensity. Rana Ayyub, an investigative journalist and columnist, has endured sustained online harassment, death threats and financial investigations (Kashmir Times, 2025). Her experience reflects the digital weaponization of gendered abuse against women journalists who challenge majoritarian narratives.

In smaller towns, the violence is more direct. Rajiv Pratap, an investigative reporter in Uttarakhand, was murdered in 2025 after exposing local corruption. Raghvendra Bajpai and Mukesh Chandrakar met similar fates in Uttar Pradesh and Chhattisgarh respectively, where exposing political or corporate wrongdoing often leads to fatal retaliation (Newslaundry, 2024). While the geography differs, the logic remains the same, dissenting voices must be neutralized. The state, through silence or complicity, allows impunity to flourish (RSF, 2025). The message is unmistakable: journalism that confronts power has no sanctuary.

in Kashmir, this logic has been perfected into a system. Every case, every raid, every arrest adds another layer to the architecture of control. It is not just about silencing individuals; it is about erasing the possibility of independent journalism altogether.

FOREIGN JOURNALISTS AND INTERNATIONAL BARRIERS

The repression of journalism in Jammu & Kashmir is not confined to domestic actors. Foreign correspondents face severe restrictions, reflecting India’s determination to control global perceptions of the region. The government has systematically reduced access for international media, using visa denials, expulsion orders and controlled press tours as tools of narrative management (Al Jazeera, 2024; Kashmir Times, 2025). The expulsion of Vanessa Dougnac, a French journalist who had lived in India for over two decades, exemplifies this strategy. Her visa renewal was rejected in 2024 after she reported on Kashmir’s human-rights situation.

Her case revealed how foreign journalists are quietly pushed out when their reporting deviates from official narratives. Others, including correspondents from major Western outlets, have been denied permission to visit Kashmir altogether. These restrictions effectively seal the region from external scrutiny (Kashmir Times, 2025). Beyond the Valley, this approach has extended to foreign journalists covering broader national issues of governance and accountability. In early December 2023, American journalist Raphael Satter, a cybersecurity reporter for Reuters, became the target of such state retaliation. His Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) status was revoked after he published an investigative report titled “How an Indian Startup Hacked the World.”

The story revealed the operations of an Indian cybersecurity firm, Appin and its co-founder Rajat Khare, describing how the company had evolved into a “hack-for-hire powerhouse” targeting politicians, military officials and religious institutions across several countries. Following its publication, the Ministry of Home Affairs accused Satter of “tarnishing India’s reputation” and subsequently rescinded his OCI card (Al Jazeera, 2023; Newslaundry, 2024).

During his investigation, Satter reportedly received multiple warnings and threats, including intimations of “diplomatic action” should he persist in covering Appin’s activities. His experience illustrates how the Indian state deploys its legal and diplomatic instruments not only to deter domestic dissent but also to suppress foreign reporting that challenges its preferred global image (Al Jazeera, 2023). The case underscores a growing trend in which international journalists—long seen as essential intermediaries between India and the world—are treated as potential adversaries rather than partners in transparency.

These developments are accompanied by intensified visa restrictions for foreign media outlets. Journalists seeking to report from Kashmir or other sensitive regions encounter opaque approval processes, sudden visa denials and prolonged security clearances that effectively prevent timely coverage. The central government justifies these actions through the rhetoric of national security and public order. Yet in practice, they have transformed India’s democratic institutions into instruments of information containment (Kashmir Times, 2025; RSF, 2025). By restricting on-the-ground documentation, the state ensures that global audiences remain dependent on filtered or outdated narratives, thereby minimizing international criticism of human- rights abuses in Kashmir.

Foreign journalists who manage to enter face logistical and bureaucratic barriers. They are required to obtain special permission from the Ministry of Home Affairs and are often accompanied by government “liaison officers.” These escorts monitor their movements, limit their access to conflict zones and sometimes dictate who they may interview. Such supervision turns reporting trips into staged exercises, ensuring that only sanitized versions of reality reach international audiences (Al Jazeera, 2024). The censorship extends beyond physical control to digital manipulation. The government pressures international media houses to “respect India’s sovereignty” and avoid “biased” coverage of Kashmir. Stories highlighting human-rights violations or restrictions on civil liberties are dismissed as foreign propaganda.

This approach fosters a global silence that isolates Kashmiri journalists and minimizes international outrage (RSF, 2025). For many foreign correspondents, the risks are professional rather than physical. Those who report critically face withdrawal of accreditation or non-renewal of long-term visas. Their local stringers and fixers, however, face far greater danger. They are interrogated, detained, or barred from future collaboration with foreign media. As a result, even global outlets struggle to find reliable local partners willing to take the risk of association (Kashmir Times, 2025). The suppression of foreign reporting serves a dual purpose. Domestically, it allows the state to present an image of stability and “normalcy.” Internationally, it prevents the formation of an evidence-based counter-narrative. By restricting both internal and external journalism, the government ensures that Kashmir’s story remains tightly controlled (Al Jazeera, 2024; RSF, 2025).

ECONOMIC AND STRUCTURAL COLLAPSE OF THE MEDIA ECOSYSTEM IN JAMMU AND KASHMIR

Financial Strangulation through Advertisement Denial The media ecosystem in Jammu and Kashmir faces systematic economic collapse. Independent newspapers and digital platforms struggle to survive. The state has weaponized financial control to restrict press freedom. Government advertisements, a key revenue source for local media, are withheld from critical outlets (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2019). Allocation is opaque and politically selective. Pro-government media continues to receive funding, while independent publications face financial suffocation (Mittal, 2025).

Local newspapers rely on advertisement revenue to cover salaries, printing, distribution and operational costs. For instance, many district-level newspapers in Anantnag, Pulwama and Baramulla operate on margins of less than ₹50,000 per month (~US $600 / ~PKR 245,000). Withdrawal of government ads has rendered these operations unviable. Editors have publicly protested, insisting that advertisements are a public resource, not a political privilege (Kashmir Age Online, 2025). The Kashmir Walla, once a leading independent platform, exemplifies the crisis. It faced repeated shutdowns, staff layoffs and dwindling revenue. Investigative journalism nearly ceased due to the absence of stable funding.

Other local media houses report similar patterns. Around 35 independent newspapers and 15 digital platforms shut down between 2016 and 2023, primarily due to economic pressure (Al Jazeera Media Institute, 2025). Television and radio stations also struggle. Local channels in Srinagar and Jammu report a 40–50% decline in private sponsorship over the past five years. National companies avoid placing advertisements due to fear of political backlash. The resulting economic squeeze forces editorial compliance. Quality and credibility are subordinated to survival.

The financial crisis also undermines regional representation. District-level bureaus in Kupwara, Bandipora, Kulgam and Shopian have closed. Reporters covering local governance, human rights and security incidents have either gone freelance or left journalism entirely. Investigative reporting, once a hallmark of Kashmiri media, is nearly extinct outside pro- government outlets. Advertisement denial has created a dual-class media system. Compliant platforms receive stable funding, while independent media operates under chronic uncertainty. Newspapers report delays in salary payments of three to six months. Freelance journalists, who constitute over 40% of the reporting workforce, face irregular compensation, ranging between approximately US $60–180 / (PKR 24,500–73,500). These conditions make journalism unsustainable.

Cumulatively, financial deprivation reduces public access to information. Reports on civil rights violations, administrative failures and electoral transparency are scarce. The economic chokehold ensures that only politically aligned narratives dominate public discourse. This structural financial control has transformed the media from a watchdog into a controlled extension of governance. Youth Disillusionment and Professional Decline Economic pressures have deepened professional disillusionment among aspiring journalists. Enrollment in journalism programs in Jammu and Kashmir has dropped drastically. Universities in Srinagar and Jammu report only 25–30 graduates annually, compared to 100– 120 a decade ago. The profession is now seen as risky, low-paying and insecure (Al Jazeera Media Institute, 2025).

Graduates confront a shrinking job market. Local newspapers cannot afford to hire and digital platforms struggle to pay regular salaries. Newsrooms prioritize survival over investigative reporting. Career paths that once promised growth and impact now lead to precarity. Over 60% of new graduates migrate to metropolitan centers such as Delhi, Mumbai and Bangalore. Others relocate abroad to countries offering professional security.

The departure of skilled journalists exacerbates the crisis. Experienced reporters leave a knowledge gap in local news coverage. Districts such as Shopian, Anantnag and Kupwara experience almost no investigative journalism. Young reporters entering the profession face limited mentorship. Media houses struggle to maintain institutional memory, which undermines long-term reporting quality. Journalism itself has shifted from a societal watchdog to a role aligned with state-sanctioned narratives. The Strategic Erasure of Independent Journalism in Jammu & Kashmir15 Investigative reporting has declined sharply. Ethical independence is compromised by financial dependency.

Public discourse is increasingly filtered through the lens of compliance. Newspapers now report selectively, emphasizing non-controversial stories or lifestyle content. The psychological burden on young journalists is severe. Fear of detention, harassment and surveillance discourages critical reporting. Journalists avoid covering political unrest, human rights violations, or security operations. Risk-taking is rare and ambition is curtailed. The profession’s appeal diminishes, leading to long- term attrition. District-level examples illustrate this collapse. In Kupwara, only two local reporters cover administration and security updates. In Pulwama, young journalists report that investigative work is “career suicide.” Salaries in these districts average US $84–144 / per month (PKR 34,300–58,800), insufficient for professional sustainability. Meanwhile, metropolitan media centers absorb local talent, leaving Kashmir with a depleted journalistic workforce.

This structural decline threatens the future of the profession. Reduced youth participation weakens independent reporting. Without institutional support, the ecosystem cannot foster investigative journalism. Media houses prioritize compliance over accountability, leaving the public with fragmented information. Digital and Social Media: The Last Breathing Space As print and broadcast media collapse, digital platforms initially offered alternatives. Independent websites, blogs and social media channels became vital spaces for reporting. Digital platforms allowed journalists to reach national and international audiences, bypassing traditional constraints.

However, online reporting is under heavy surveillance. Security agencies use AI-based algorithms to monitor social media content. “Cyber volunteers” amplify pro-government messaging and flag critical content. Journalists must self-censor. Reporting on political issues, human rights, or protests can trigger harassment, detention, or financial penalties. The infrastructure for digital journalism remains weak. Independent platforms face high operational costs. Maintaining servers, hosting secure websites and moderating content requires funding often exceeding US $1,200 / annually (PKR 490,000). Advertising revenue is constrained by political pressures. Many journalists rely on crowdfunding or subscriptions, but the financial model remains unsustainable.

Internet shutdowns further disrupt digital reporting. Jammu and Kashmir experience approximately 200– 250 shutdowns between 2016 and 2023. These range from complete internet blackouts to mobile-only restrictions. Shutdowns during elections, protests, or security operations isolate journalists from sources and audiences. Recovery is slow and the memory of interruptions enforces cautious reporting. Digital surveillance extends beyond content monitoring. Authorities track metadata, private messages and source communications. Facial recognition tools and social media analytics create a pervasive climate of fear. Journalists in Srinagar report that even sharing a news link can attract scrutiny. Risk-taking is rare and investigative reporting is minimized.

Despite constraints, digital media retains significance. Platforms like Twitter, Facebook and local news websites allow some dissemination of sensitive information. Coverage of detentions, forced disappearances and human rights violations still occurs, albeit in limited scale. However, fragmented reach and surveillance reduce the overall societal impact. Digital journalism faces indirect economic pressures as well. Platforms rely on unstable funding and volunteer contributors. Payment delays and inconsistent revenue affect reporting quality. Some digital outlets survive solely through external grants or diaspora support, rendering independence precarious.

The digital domain also experiences geographic disparities. Districts like Ganderbal, Bandipora and Kulgam suffer from poor connectivity, affecting reporting and communication. Journalists in rural regions operate under technological and financial constraints. Internet shutdowns disproportionately affect these areas, silencing voices that most need to report local grievances. The interplay of economic, professional and technological pressures reshapes journalism in Kashmir. Newspapers close, young professionals exit the field and digital platforms operate under constant threat. Independent media is financially fragile, professionally constrained and socially circumscribed.

Societal and Civic Consequences

The collapse of journalism has severe societal consequences. Public access to information is limited. Civic awareness declines. Citizens receive filtered narratives, often aligned with state interests. Accountability mechanisms weaken. Mismanagement, corruption and human rights violations escape scrutiny. District-level examples illustrate this trend. In Anantnag, lack of investigative reporting has left local administration unmonitored. In Baramulla, reporting on health infrastructure deficits and school closures is minimal. Citizens rely on fragmented news from pro-government channels. Independent voices are marginalized.

The attrition of journalists also reduces coverage of socio- economic issues. Education, healthcare, employment and environmental reporting are largely neglected. Without investigative oversight, public policy remains unexamined. Media’s role as a watchdog is severely diminished. The combined effect of advertisement denial, youth disillusionment and digital surveillance ensures that independent media in Kashmir remains weak. Audiences receive partial, filtered, or sanitized information. Pluralistic reporting has largely disappeared. Future journalists face a financially unstable profession, professionally restrictive and socially constrained.

Structural Imperatives for Reform Unless systemic reforms occur, the collapse will continue. Media independence requires financial stability. Advertisement allocations must be transparent and apolitical. Young journalists need safety, training and career prospects to remain in the field. Digital platforms require secure infrastructure, funding and legal safeguards. Restoring independent journalism is essential for democracy and accountability. Without reform, investigative reporting will remain rare. Civic participation will decline. Public trust in media will erode. The professional exodus will accelerate.

Compliance will replace credibility. In conclusion, the economic and structural collapse of the media ecosystem in Jammu and Kashmir is multifaceted. Financial strangulation, professional decline and digital repression interact to produce a weakened, vulnerable and fragmented media landscape. Independent journalism is financially insecure, professionally marginalized and socially constrained. Public access to information is shrinking. Investigative reporting is rare. Districts across Kashmir experience disparities in coverage. Future journalists face limited opportunities and unsafe working conditions. Immediate structural reform is critical to restore media independence, uphold accountability and safeguard the public’s right to information (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2019; Mittal, 2025; Al Jazeera Media Institute, 2025; Kashmir Age Online, 2025).

TRAUMA, FEAR AND SOCIAL STIGMATIZATION

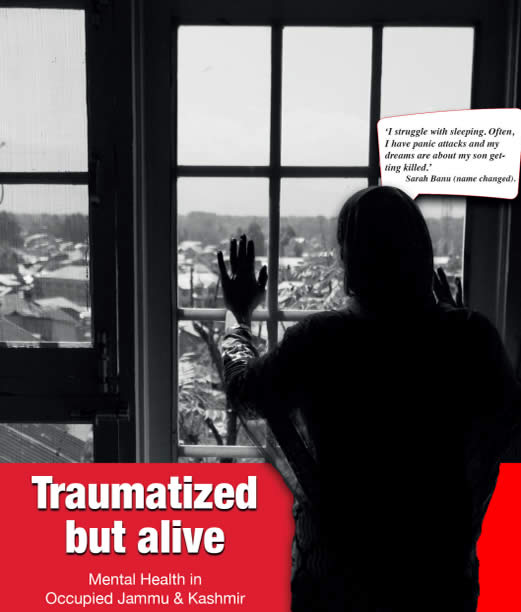

The toll on journalists in Jammu & Kashmir is profound. Detention, raids, background checks and surveillance impose heavy psychological burdens. Family life, career prospects and mental health are all affected (Kashmir Awareness, 2023a). Between 2020 and December 2023, the region recorded over 2,700 bookings under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) and the Jammu & Kashmir Public Safety Act (PSA). Of these, 1,100 were labelled as “over-ground workers” or facilitators for armed groups (Kashmir Times, 2024a). For journalists, the impact is both direct and indirect. At least six journalists in J&K have been formally charged under UAPA. Four of them were also charged under the PSA (Kashmir Times, 2024b).

As of January 2024, four of the seven jailed journalists in India were from J&K. Two were booked under UAPA and two under PSA (Kashmir Times, 2024b). These legal cases are not just legal matters. They generate fear, trauma and stigmatization. A journalist from Srinagar reported: “They kept asking why I’d done it. They said they knew everything about me and my family which was very scary” (Kashmir Awareness, 2023b). Such testimonies reflect the personal cost. Detention disrupts daily life. Families of detainees face economic hardship (Sabrang India, 2023). When a journalist is detained, the family is often the first to feel the shock. Children miss school, spouses lose income and social networks shrink. The stigma attaches socially and professionally.

Travel bans and passport cancellations are common. One RTI revealed that 16,329 individuals had been detained under preventive detention laws since 1988; nearly 95% were from Kashmir (Sabrang India, 2023). Journalists are among those barred from travel abroad without explanation (Free Speech Collective, 2023). Loss of mobility means loss of opportunity, exposure and networks. The emotional impact is layered. Former detainees report nightmares, anxiety and insomnia. Some cannot return to the field. One journalist described his career post-detention as “career suicide” (Kashmir Awareness, 2023c).

Loss of livelihood is acute. Many local media outlets in J&K are economically fragile. Independent publications struggle. When a journalist is detained, the outlet loses expertise. The family may not sustain dependent income. The cumulative effect is attrition from the profession. Some leave journalism entirely. Social isolation combines with professional stagnation. Journalists report being excluded from assignments, denied accreditation, or sidelined. Some cover “safe” lifestyle stories rather than governance or human rights. That shift is survival-driven. The stigma extends to peer groups. When one journalist is raided, others self-censor. When a family is threatened, the journalist may choose silence instead of risk. The community of journalists shrinks and trust erodes. One senior editor observed: “It is almost impossible. There is so much surveillance, so many different ways of harassment” (Kashmir Awareness, 2023d). Trauma is not only individual, it is collective. The profession in J&K bears the weight of fear, isolation and stigma.

SELF-CENSORSHIP AND THE INTERNALIZATION OF FEAR

Fear becomes embedded in routines. Reporting becomes a risk calculation. Journalists in J&K regularly ask: “Is this story worth the cost?” The logic is no longer only editorial or professional. It is survival (Kashmir Awareness, 2023e). Since August 2019, over 40 journalists in J&K have been summoned, background-checked, or raided (Kashmir Awareness, 2023f). The architecture of surveillance is extensive. One section of the police called “Dial 100 – background updation” checks journalists’ body of work, family relations and foreign travel (Kashmir Awareness, 2023g). Others operate under the “Ecosystem of Narrative Terrorism” unit (Kashmir Awareness, 2023h).

These structures impose a chilling effect. When a home raid becomes normal and when a journalist knows his family could be summoned, self-censorship becomes rational. A story on governance or security may invite interrogation or worse. Decision-making is dominated by survival. Institutionalized self-censorship is now a reality in many newsrooms in J&K. Interviewing government critics, investigating local administration issues and covering security operations are all high-risk. Local newspapers depend on government advertisements and fear withdrawal if they run critical stories (Amnesty International, 2020).

Some journalists avoid bylines, write under pseudonyms, or outsource sensitive stories. The internalization of fear shifts the profession from reporting to managing risk. One senior reporter described journalism now as “an act of survival” (Kashmir Awareness, 2023i). This recalibration has tangible consequences. Investigative journalism declines. Coverage of local governance, rights violations, or security incidents shrinks. The narrative aligns more with state priorities. Young journalists entering the profession see it as precarious. They ask: Will I be able to speak the truth? Will my family suffer? Many opt out. Career pathways narrow. Loss of talent reinforces self-censorship among those who stay.

The constant calculation of risk affects story selection. Journalists avoid protests or sensitive interviews to reduce exposure. Peer groups normalize this adaptation. The default question becomes, “Do I want this assignment?” rather than, “Is this story important?” Quantitative indicators support the qualitative observations. In 2022, the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) reported a 17.9% increase in UAPA cases nationwide; the majority were from J&K (Times Headline, 2022). Several journalists reported that more than 90% of their colleagues had been summoned or interrogated (Kashmir Awareness, 2023j). Impact on content is visible. Print outlets that once carried investigative pieces now seldom do. Archives of independent papers have disappeared or been partially erased (Kashmir Times, 2024a). The void in institutional memory reinforces the culture of silence.

Travel restrictions exacerbate self-censorship. Many journalists cannot attend international conferences, accept fellowships, or collaborate abroad. Professional networks are limited, reinforcing the internalized fear. Psychological stress from self-censorship is underreported. Journalists feel guilt for “not doing the story”, anxiety about future assignments and fear of harassment. Some leave the field entirely; others shift to non-sensitive beats. The alarm bells of the profession are quiet. Societal consequences are profound. Public discourse in J&K becomes limited. Citizens receive filtered information. The watchdog role of media diminishes.

Democracy suffers.

Trauma, fear and stigmatization combine with institutionalized self-censorship to create a fragile media ecosystem in Jammu & Kashmir. Journalists are constrained by laws, raids and internalized risk. Economic precarity and professional isolation amplify the problem. Investigative journalism declines, talent shrinks and editorial independence erodes. Structural reform alone is insufficient. Human rehabilitation is essential. This includes psychological support, guaranteed travel and mobility rights, employment security and protections for those who dare to report. Unless the fear-calculus is disrupted, journalism in J&K remains a survival exercise rather than a public service.

The scale of repression is evident: thousands booked under anti-terror laws, multiple journalists detained, archives erased, self-censorship widespread. The human, professional and societal costs are immense. To restore media as the fourth pillar of democracy in J&K, structural and human interventions must proceed together.

STATE-ORCHESTRATED NARRATIVE ENGINEERING

The control of narratives in Jammu & Kashmir represents a calculated and systematic effort by the state to reshape public perception. Since August 5, 2019, when the government revoked Article 370 and restructured the region, media control has intensified. The phenomenon extends beyond conventional censorship. It is a multi-layered strategy combining editorial direction, surveillance and policing of language. Its objective is clear: manufacture consent and suppress dissent. Manufacture of Consent through Editorial Control The manipulation of media content has been a central strategy to control the Kashmiri narrative.

Reports from media watchdogs show that pro-government narratives dominate the pages of both local and national newspapers covering Kashmir. An analysis by The Wire found that between August 2019 and December 2022, over 65% of coverage from mainstream newspapers framed the situation in the region as “returning to normalcy,” emphasizing development projects, tourism and infrastructural initiatives (The Wire, 2023a). Critical incidents, including protests, curfews and detentions, were either marginalized or reported as isolated events rather than structural issues.

The use of external institutions to produce editorial content has further strengthened this engineered narrative. Think tanks such as the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) and the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA) have provided reports and opinion pieces framing Kashmir in line with state objectives. Some editorials have even drawn upon AI-generated analysis to project a narrative of stability and progress, presenting statistical indicators of development while obscuring human rights violations (ORF, 2022). This fusion of algorithmic content generation and think- tank resources ensures that narratives remain aligned with government interests and dominate mainstream discourse.

Journalists in Kashmir have noted a subtle yet profound shift. Coverage of administrative failures or military excesses is discouraged, either through editorial pressure or direct instruction. One senior journalist from Srinagar noted: “Stories that question the state’s performance are quietly sidelined. Even when they are published, headlines are edited to project positivity” (Kashmir Awareness, 2023a).

This manipulation has transformed journalism from an independent act of reporting into a tool of state propaganda. The repeated framing of Kashmir as a region moving toward “normalcy” creates a perception among national and international audiences that the conflict is resolved, when in fact curfews, communication blackouts and administrative detentions remain The Strategic Erasure of Independent Journalism in Jammu & Kashmir19 frequent. In 2022 alone, the administration imposed 34 communication blackouts, disrupting media reporting and public communication (Internet Shutdown Report, 2023).

Furthermore, the financial dependence of media outlets on government advertisements compounds this effect. According to the Kashmir Press Club, 78% of advertisement revenue for local newspapers comes from government allocations (KPC Report, 2023). Editors face implicit or explicit pressure to conform content to retain financial viability. The resulting editorial landscape is skewed toward state-sanctioned narratives. Policing of Language and Representation The second layer of narrative engineering lies in the policing of language. Reporting critical of the administration is routinely labeled “anti-national” or accused of “glorifying terrorism.” This labeling creates both legal and social consequences for journalists.

The invocation of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) and Public Safety Act (PSA) against reporters has become a common tactic. For instance, photojournalist Masrat Zahra was booked under UAPA in April 2021 for social media posts deemed “anti- national” (Amnesty International, 2021). Language policing extends beyond legal instruments. Journalists frequently experience online harassment, doxxing and smear campaigns. Social media platforms amplify these narratives. Pro-government actors often tag journalists as “separatist sympathizers” or “foreign agents,” creating a climate of fear. For reporters, even neutral coverage of civil unrest may attract such labels.

In the past four years, over 43 journalists in J&K were issued lookout notices barring them from international travel, citing concerns that their reporting might tarnish the image of the state (Kashmir Awareness, 2023b). Erasure of dissenting voices is particularly pronounced on national platforms. Many Kashmiri reporters have faced denial of accreditation for national media, effectively limiting their ability to shape narratives outside the valley. Local reporting that contradicts government narratives is rarely amplified nationally, while pro-state stories gain prominence. As a result, national audiences often perceive Kashmir through a heavily curated lens.

The erasure of dissent is not limited to journalists alone. Activists, academics and human rights defenders face similar restrictions. For instance, Khurram Parvez, a prominent human rights defender, has been prevented from travelling internationally to present reports on rights violations (Human Rights Watch, 2022). This exclusion reinforces the state’s monopoly over the narrative and reduces the visibility of dissenting perspectives.

Cultural and Gendered Dimensions

The orchestration of narratives also intersects with gender and culture. Women journalists in Kashmir face targeted harassment, both online and offline. Masrat Zahra, one of the most prominent female photojournalists in Kashmir, experienced threats, doxxing and communal slurs following her coverage of protests (Amnesty International, 2021). The aim is twofold: to intimidate the individual journalist and to send a broader signal to other women in media. Rana Ayyub, reporting for national outlets, has also been subjected to online harassment and personal threats, including communal slurs targeting her gender and religious identity (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2022). These threats are not merely incidental. They reflect a deliberate strategy of silencing women through gendered intimidation, exploiting societal prejudices to limit professional participation.

Cultural narratives are similarly engineered. By framing Kashmir as a post-conflict zone moving toward development, the state seeks to suppress local cultural and political identities. Reports celebrating local culture, highlighting historical grievances, or questioning policies are often depicted as obstacles to “normalcy.” The result is a flattening of public discourse and a homogenization of media narratives that align with state objectives. The combination of gendered harassment and cultural erasure has measurable effects. Female journalists report self-censorship at rates higher than male counterparts. Over 60% of women reporters in Kashmir have altered story angles to avoid personal risk (Kashmir Press Club Survey, 2023). Male journalists report similar changes, but the intensity is amplified for women due to threats of sexualized abuse and communal targeting.

The professional consequences of these practices are severe. Women journalists either leave the region, relocate to safer environments, or shift to less controversial beats. This attrition reinforces male- dominated reporting spaces and further narrows the spectrum of voices in the media. The Broader Societal and Psychological Impact State-orchestrated narrative engineering extends its influence beyond journalism. It shapes public perception and limits access to diverse information. Citizens, especially in remote areas, rely on local media. When reporting is skewed, the public receives a filtered view of events, often aligned with state priorities.

Psychologically, journalists internalize these pressures. Continuous labeling, harassment and surveillance induce anxiety, fear and trauma. A survey conducted by the Kashmir Press Club in 2023 found that over 80% of journalists reported stress and fear of reprisal influencing their reporting choices (KPC Report, 2023). Many describe decision-making as a “risk calculation,” weighing the professional value of a story against potential legal and social consequences.

The social effects are equally pronounced. Families of journalists face scrutiny, ostracism and economic repercussions. Travel restrictions limit career mobility. Collectively, these pressures reinforce compliance, leading to a media ecosystem where dissenting perspectives are marginalized and self-censorship

becomes the norm.

Case Examples

A few illustrative cases highlight these dynamics: Masrat Zahra: Booked under UAPA for social media posts, she faced gendered abuse online. Her work documenting protests was effectively criminalized (Amnesty International, 2021). Gowhar Geelani: Detained at the airport in 2019 to prevent him from joining Deutsche Welle in Germany. His reporting for international media was deemed a threat to the official narrative (Kashmir Awareness, 2023c). Rana Ayyub: Threatened and doxxed online, reflecting gendered targeting that seeks to silence women journalists reporting critically on Kashmir (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2022).

Hilal Mir and Shah Abbas: Journalists raided in 2023, illustrating the routine application of intimidation to control narratives and enforce self-censorship (Kashmir Awareness, 2023f). These cases collectively demonstrate a systematic pattern of harassment, erasure and intimidation. They reflect the state’s broader objective of narrative dominance. State-orchestrated narrative engineering in Jammu & Kashmir is a multi-dimensional strategy. It operates through editorial control, policing of language and targeted harassment with cultural and gendered dimensions. Its consequences are both structural and personal. Journalism is transformed into a controlled apparatus. Independent reporting declines. Self- censorship becomes institutionalized.

Public perception is carefully curated to present an illusion of normalcy. The long-term effects are profound. Media becomes a mechanism for manufacturing consent rather than a check on power. Public debate narrows. Gendered and cultural voices are silenced. The psychological burden on journalists, particularly women, compounds the societal impact. To safeguard democracy and press freedom in Kashmir, interventions must extend beyond legal reform. Independent editorial spaces, protection for journalists and mechanisms to amplify dissenting voices are essential. Without these, the region risks a continued monopoly over narratives, eroding both media integrity and public trust.

LEGAL AND DEMOCRATIC IMPLICATIONS

The repression of journalists in Jammu & Kashmir represents more than a regional concern. It constitutes a direct assault on constitutional guarantees and international law. Since August 5, 2019, the revocation of Article 370 intensified the state’s control over information. Journalists face preventive detentions, travel bans and raids. Legal frameworks meant to protect citizens are subverted to target media. The resulting environment reflects a crisis of both law and democracy.

Contradictions with Constitutional and International Law

The Indian Constitution enshrines freedom of expression under Article 19(1)(a). It guarantees every citizen the right to express opinions freely. Article 21 protects the right to life and personal liberty. In Jammu & Kashmir, these rights are systematically undermined. The routine use of the Public Safety Act (PSA) and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) against journalists exemplifies this erosion. For instance, Asif Sultan, editor of The Kashmir Walla, was detained under PSA in 2018. He spent over 1,000 days in detention without trial (Press Freedom Tracker, The Strategic Erasure of Independent Journalism in Jammu & Kashmir21 2023). Such prolonged preventive detention violates Article 21’s guarantee of liberty. Similarly, journalists like Masrat Zahra were booked under UAPA for social media posts (Amnesty International, 2021). These laws are framed for counter-terrorism, yet they are applied to suppress dissenting voices.

Internationally, India has ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Article 19 of ICCPR guarantees freedom of expression and Article 14 enshrines the right to a fair trial. Yet, the preventive detention of journalists, censorship and travel restrictions in Kashmir contravene these obligations. The detention of Gowhar Geelani in 2019, preventing him from joining Deutsche Welle in Germany, highlights this contradiction (Kashmir Awareness, 2023a). Despite international norms, judicial mechanisms rarely intervene decisively. Courts delay hearings or uphold detentions citing “national security,” further entrenching impunity.

Judicial reluctance compounds the problem. Preventive detentions under PSA are reviewable by advisory boards. However, these boards often function with delays exceeding six months. In Qazi Shibli’s case, he was detained for eight months with minimal judicial oversight before temporary release (KPC Report, 2023). The judiciary’s inaction normalizes arbitrary restrictions on journalists.

Weakening of Institutional Checks

Institutional safeguards meant to ensure press freedom are compromised. The Press Council of India (PCI) is mandated to uphold media independence and ethical standards. Yet, in Jammu & Kashmir, its influence is negligible. When journalists face raids or harassment, the council’s interventions are limited to statements. They lack enforcement powers. Meanwhile, local media operates under constant surveillance and financial pressure. Government advertisements constitute over 70% of revenue for regional newspapers (KPC Report, 2023). Editors are thus incentivized to align with official narratives. Legislative oversight is absent in preventive detentions and censorship. Parliament rarely debates PSA or UAPA use in the context of journalism. In 2021, an analysis of parliamentary records revealed zero substantive discussions on media freedom violations in Kashmir (PRS Legislative Research, 2021). Such neglect allows executive authorities to deploy coercive tools with minimal accountability.

Courts also contribute to the weakening of checks. Many cases challenging detention or censorship remain pending for years. This judicial inertia effectively endorses administrative overreach. The cumulative effect is clear: institutions designed to safeguard democracy fail to protect the press. Journalists operate in a legal vacuum where preventive detention, raids and travel restrictions are normalized.

Democracy under Siege

The erosion of press freedom signals deeper democratic backsliding. Journalism, traditionally the fourth estate, acts as a check on power. In Jammu & Kashmir, this pillar is systematically undermined. Media repression extends beyond arrests and harassment. Institutional pressures, financial control and bureaucratic censorship collectively limit independent reporting. Self-censorship emerges as a survival strategy. Over 80% of surveyed journalists report altering or withholding stories to avoid administrative reprisals (KPC Survey, 2023). The press no longer serves its role as a watchdog. Instead, it becomes an instrument for state propaganda.

Coverage of protests, curfews, or arbitrary detentions is minimized. Positive narratives—development, tourism and infrastructure projects—dominate national coverage. This distortion weakens democratic accountability. The systemic assault on media freedom is symptomatic of broader democratic decline. Citizens in Kashmir receive filtered information. Civil society remains constrained. Elections may occur, but public debate is impoverished. Without a free press, checks on power vanish. Executive overreach becomes entrenched. Journalists face fear, isolation and uncertainty. Democracy, in practice, is hollowed out.

INTERNATIONAL REACTIONS AND HUMAN RIGHTS ACCOUNTABILITY

The repression of journalists in Jammu & Kashmir has drawn global attention. International organizations, UN mechanisms and comparative case studies provide a framework to evaluate India’s obligations and failures.

Global Condemnations

Multiple international bodies have publicly condemned India’s actions in Kashmir. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Reporters Without Borders (RSF), the International Press Institute (IPI), the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) and UNESCO have all raised alarm over press freedom violations. In 2023, CPJ highlighted the arbitrary detention of journalists and the imposition of travel bans, noting that such measures “chill reporting and erode democracy” (CPJ, 2023).

In 2025, IPI adopted a resolution urging global action to dismantle impunity structures in India (IPI, 2025). It emphasized that unchecked state power in Kashmir undermines democratic norms and international law. RSF’s World Press Freedom Index reflects this deterioration: India fell from 150th to 161st globally between 2019 and 2024, primarily due to media restrictions in Jammu & Kashmir (RSF, 2024).

These condemnations are not symbolic. They signal a growing recognition that press freedom is a barometer for democratic health. International scrutiny pressures states to consider legal reforms, judicial accountability and institutional checks. Yet, India has largely ignored these calls, asserting that media restrictions are “necessary for national security.”

UN Mechanisms and Treaty Obligations

United Nations mechanisms have repeatedly expressed concern over India’s media policies in Kashmir. The UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) has urged India to repeal repressive laws, including PSA and UAPA, insofar as they affect journalists (UNHRC, 2022). The UN has called for the restoration of civic space and unhindered access for journalists, highlighting that preventive detentions contravene ICCPR obligations. India also faces non-compliance with Universal Periodic Review (UPR) recommendations. During the 2020 UPR cycle, several states urged India to safeguard press freedom, provide judicial remedies for journalists and lift arbitrary restrictions (UN UPR, 2020). Despite these recommendations, over 40 journalists have been detained or harassed post-2019. Many face travel restrictions, while several publications continue to operate under strict censorship.

UN Special Rapporteurs have also commented on India’s media environment. They observe that systematic harassment and preventive detention not only violate constitutional guarantees but also international human rights law. For example, the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression urged India to ensure that legislation like UAPA is not misused against journalists (UNHRC, 2022).

Comparative Perspective

The repression of media in Jammu & Kashmir is not unique globally, but it exhibits distinctive characteristics. Conflict zones such as Palestine and Myanmar also witness emergency laws restricting media freedom. In Palestine, Israeli authorities impose censorship under security pretexts. In Myanmar, the military junta criminalizes reporting critical of state actions. However, India’s model is unique due to its veneer of democracy. Unlike overtly authoritarian regimes, India maintains elections, a functioning judiciary and multiple political parties. This “bureaucratised censorship” operates under the guise of legality. Laws like PSA and UAPA, media policies and government advertisements constitute tools of control, all while preserving the appearance of democratic normalcy.

The Indian case illustrates the dangers of “administrative authoritarianism.” Legal instruments designed for counter-terrorism are repurposed to suppress journalism. Judicial delays and legislative inaction reinforce the executive’s monopoly over narratives. The result is a hybrid model: democracy exists in form, but press freedom and civic space are severely constrained. Implications for Human Rights and Accountability The cumulative impact of domestic suppression and international non-compliance is profound. Journalists face existential threats to their careers and freedom. Society loses critical information.

Democratic processes function under constrained conditions. Internationalmechanisms, though vocal, struggle to enforce accountability. The combination of legal, bureaucratic and societal pressures ensures the persistence of state- controlled narratives. Preventive detentions, raids, travel bans and online harassment constitute a multi-layered strategy. Legal structures intended to protect citizens are weaponized against those holding power accountable. The systemic attack on journalists signals that press freedom, as a democratic pillar, is under siege.

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

Independent journalism in Kashmir faces near-collapse. The Press Council of India, mandated to safeguard journalistic independence, remains largely ineffective in the valley. Its condemnations carry no enforcement power, allowing harassment to continue unchecked. The Strategic Erasure of Independent Journalism in Jammu & Kashmir23 Legislative and judicial oversight is similarly weak. Parliamentary records show no substantive debates on media repression in Kashmir between 2019 and 2022 (PRS Legislative Research, 2022). Courts, despite formal independence, provide delayed or inadequate remedies. The eight-month PSA detention of journalist Qazi Shibli proceeded with minimal judicial scrutiny (KPC Report, 2023), reflecting the broader failure of institutional safeguards.

This institutional fragility has reshaped newsroom behavior. Local outlets increasingly rely on state- sanctioned narratives, avoiding stories involving curfews, arbitrary detentions, or human rights abuses. The administration’s financial leverage deepens this dependence. Under the 2021 Media Policy, government advertisements may be withheld from outlets publishing “material questioning sovereignty or inciting violence” (J&K Media Policy, 2021). This mechanism embeds censorship within economic regulation, aligning editorial priorities with official expectations.