The Intersectional Struggles of Women under Repressive Laws in Indian-Occupied Jammu and Kashmir

The Intersectional Struggles of Women under Repressive Laws in Indian-Occupied Jammu and Kashmir

Abstract:

In conflict zones, women’s body, home, and ascribed roles within society, often becomes a site of contestation and control. However, in the case of Indian Occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IOJK), the impact of draconian laws like Armed Forces Special Power Act (AFSPA) and Public Safety Act (PSA) is not uniform. It is influenced by multiple social roles and identities, which include gender, ethnicity, social class, and religion. Thus, the study uses Kimberlé Crenshaw’s intersectionality model to give a layered perspective of how gender violence can not be comprehended in isolation from other forms of oppression. By employing the Boolean search method and qualitative exploratory approach, the research builds upon several scholarly articles, reports and ethnographic case studies.

By Syeda Shafia Batool

BS-IR (8TH) National Defence University Islamabad

One such case study discussed in this paper revolves around the life of a mother and an activist Parveena Ahanger, who lost her son to enforced disappearances. Her determination not only symbolizes the strength of the Kashmiri women, but at the same time, it also unmasks the prejudice they have to endure because of their multiple marginalization. The findings of this research underscores the need to engage a more complex and intersectional analysis in order to effectively understand the suffering of Kashmiri women under the combined oppression of militarized and political subjugation of AFSPA and PSA. In this way, through amplifying women’s voices and lived experiences, this paper seeks to shift from the conventional gender sensitive policies, to context relevant approaches that adequately capture the multiplicities of women’s identities and experiences within volatile areas such as IOJK.

Keywords: Intersectionality, Public Safety Act (PSA), Armed Forces Special Power

Act (AFSPA), Gender-based violence, half-widows, IIOJK, UNHCR-132 resolution,

Women, Peace and Security (WPS).

Introduction

“There's really no such thing as the 'voiceless'.

There are only the deliberately silenced, or the preferably unheard.” ―

Arundhati Roy

The position of women in the disputed territory of Indian Occupied Jammu & Kashmir, has been a subject of systematic violence and repression under the draconian laws like AFSPA and PSA. The enforcement of these laws which empowers Indian occupation security forces to curb violence in the name of restoring law and order in the region have had gross impacts on the livelihood of the Kashmiri women. By acknowledging that women’s experiences are different but interconnected, the intersectionality frame work by Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991) is useful in explaining these impacts, most of which are as a result of social categories such as gender ethnicity, colour, class, and religion among others. This research used an exploratory, qualitative research design to understand multiple and multifaceted experiences of women living under oppressive laws in IIOJK.

Since the aim was to obtain accurate information, Boolean searching

techniques were used in various scholarly databases and sources. This technique

enabled to select the literature, reports, and cases in line with the concerns

of gender, ethnic, and class dynamics regarding state repressive strategies in

IIOJK. Moreover, the research specifically employed a case study of Parveena

Ahanger - a mother of a disappeared son who being a woman, a mother and a

political activist has been put under the menace of both gender violence and

political persecution. Despite being portrayed as a symbol of resistance due to

her unrelenting determination to fight for justice, she has to undergo personal

and social suffering which will be subsequently deconstructed through

Intersectional analysis. In this way, Intersectionality opens up a better

understanding of how these cross-cutting social categorizations defines

experiences of oppression and survival, underlining the significance of

adopting more complex and intersectional approaches to meet the needs of

Kashmiri women.

Impacts

of AFSPA and PSA on Kashmiri Women

The

Constitution of India claims to protect civil liberties and individual rights

like the right to life and liberty, freedom of speech, and equality before law.

These rights are legal and can be defended in Supreme Court, yet, these rights

are not inviolable and may be terminated for the sake of safeguarding the state

security. Such an approach becomes especially problematic when applied in

territories such as Indian-Occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IOJK), where the state’s

security forces can independently determine which regions are ‘disturbed,’ and

therefore require military intervention. When an area is declared ‘disturbed’,

state’s civil authority is replaced by military force and here civic issues

become security issues. This shift in the process practically marginalizes

civil institutions and shifts the policing function to the military, which

challenges the balance of powers between civil and military authorities. The

People’s Union for Democratic Rights noted that the declaration of the affected

area as disturbed one actually means handing over the area to the army and in

this way it renders the civil power irrelevant. Some scholars have also

referred to this state of affairs as the procedural martial law, which enjoys

no constitutional sanction and is synonymous with serious violation of human

rights.

In

the case of Indian Occupied Jammu and Kashmir, the whole area of Kashmir valley

is regulated by the Disturbed Areas Act, Armed Forces Special Power Regulation

Act (AFSPA), and the Public Safety Regulation Act (PSA). The Disturbed Areas

Act is crucial for AFSPA implementation because it empowers the security forces

with specific authority to arrest anyone without warrant and to issue shoot at

sight order. It further grants blanket protection to the security forces,

precluding them from arrest for alleged criminal acts, including murder and

rape. This legal shield plays its part in fostering an environment of total

lack of accountability, which leads to continued violation of human rights.

Similarly, the PSA also escalates the repressive climate in the region since

individuals are detained without any trial for up to one year. Like AFSPA, it

has no legal definitions and judicial decorum, which has made it an instrument

of political oppression instead of genuine security threats. The PSA is often

used to neutralize political rivalry and silence dissent, with detentions often

not backed by evidence, and legal representation. Both the laws AFSPA and PSA

are repressive in nature, and have affected the lives of women in Kashmir in

significant ways, in terms of their intersecting identities.

Systemic

and Intersectional Vulnerabilities Intensified by Repressive Laws

AFSPA

and PSA, which have become instrumental in IOJK have not only paved way for

impunity but have also deepened systematic and intersectional threats for women

in Kashmir. These laws tend to uphold social segregation and discrimination

making it hard for women to go about their normal duties in their society. In

order to grasp the suffering of Kashmiri women under oppressive laws like AFSPA

and PSA, it is essential to incorporate an intersectionality lens.

Intersectionality as a theory was developed in 1991 by Kimberlé Crenshaw, which

describes people’s experience as a function of one or several intersection of

social identities including gender, class, religion, ethnicity/ race among

others. When applied to the case of Kashmir, this framework offers a way of

moving beyond the reductive portrayal of women as passive receivers of violence

and instead recognizes the complex subjectivity that shapes their experiences.

In this context, I will employ a three-pronged approach to analyze their

experiences:

1.

Additive Effects: This approach aims to assess the

specific forms of oppression related to each identity that Kashmiri women have.

For instance, while mothers are subjected to the emotional shock of losing

their loved ones to state violence in the region, these women also suffer major

economic insecurity as well. This may be because of job losses or a decline in

household income due to absence of a male figure in a militarized conflict, hence

adding to their insecurity. Thus, every role, being a mother, a widow, a

survivor of violence, introduces an additional negative factor that influences

the lives of these women in general.

2.

Multiplicative Effects: The multiplicative effects

approach studies how one identity condition exponentially worsens the other to

create several disadvantages. For instance, the social labels attributed to

women with linkages to militants or political detainees ultimately hampers

their social contacts and care systems. The fact that they are mothers,

caregivers, and relatives of political detainees compounds their

marginalization and increases their exclusion from social and economic networks

on which they depend. The multiplicative effects underline how the different layers

of oppression are created by the cumulative subject positions that are

detrimental to the lives of the Kashmiri women.

3.

Intersectional Effects: The intersectional effects

approach is used to study the overlapping experiences of women living in Kashmir,

which remains under threat of state control, and often harassed with no

possibility to get justice. These women operate in a world where the roles that

they play are intertwined, with experiences of hardship based on the different

factors that make up their identity, such as being a woman, a mother, a widow

or a person in a minority group. These interconnections define their lives and

the ways in which they try to survive, resist, and adapt to the ongoing

conflict. The intersectional effects show that it is important to take into

account these multiple layers of identification to better comprehend the

peculiarities of the situation of Kashmiri women. Therefore, by adopting this

intersectional approach, the current study aims to explore the real-life experiences

of the women of Kashmir who are suffering due to oppressive laws.

Intersectional

Vulnerabilities in the Context of Conflict

The multi-faceted vulnerability of the women of Kashmir cannot be understood in isolation from the socio-political fabric of the region. Previous studies on the roles of women in the context of IIOJK usually confines them into two categories of either victims of oppression or passive supporters of resistance. However, this idea does not help in understanding the real situation of women and their role in the conditions of the state of Occupied Jammu and Kashmir. Intersectionality, on the other hand, pays attention to how other factors complicate or enhance these experiences and statuses of these women, ranging from survivors of sexual assault, widower, motherhood, and other correlated aspects of their lives like class, ethnicity, education and socio-economic status.

It shows that topics relating to the narratives of Kashmiri women are

much more complex than just the continued subjugation of these women. For

instance, Fatima, a half widow, had to wait for two years just to get her FIR

filed, which in turn worsened her trauma and also gave an insight into the

bureaucratic challenges that these women undergo. This delay is not merely a

structural gap in the available resources but also a reflection of the

problematic structure of society asserted through the mistreatment of

half-widows who enter into wage earning roles as the main bread winners of

families. This change of roles puts them at further risks of physical and

sexual assault at the check points.

Furthermore, the patriarchal environment in the Indian-occupied part of Kashmir shapes the specific legal and financial dilemma they encounter. Property laws under the Hindu Succession Act, do not acknowledge ‘half-widows’. This legal loophole deprives half-widows of inheriting property as well as accessing necessary relief services unless and until, they produce evidence of their husbands’ death. This exclusion shows how patriarchy at the structural level ensures that gendered violence continues to trail these women because they do not have economic security and freedom that is accorded to them as humans.

Their gender

as women, their roles as mothers and wives, their status as widows or sisters

and daughters of prisoners who have been detained by the state, gives them

experiences that are not easily recognized by a law that is inherently

oppressive. These challenges are further magnified by the conflict that

constrains conventional family systems, leaving women to assume responsibility

that is otherwise not suitable for them. When applied to gender and class, the

concept of intersectionality makes it possible to define how such complex

social identities lead to specific modes of oppression that cannot be explained

based on the traditional approach of a single-axis perspective on gender or

class.

Physical

and Sexual Violence

One of the most chilling manifestation of AFSPA and PSA’s effect on women in Kashmir is sexual and physical violence at the hands of security forces. Rape and sexual assault cases are rampant, and violence in its various forms is employed to ensure compliance and silence. However, such experiences show that the women who take different social positions are not equally vulnerable. For example, widows and mothers of the disappeared are most vulnerable as their connection to political detainees or militants makes them even more marginalized and ostracized.

These social implications reduce their interaction

with other community members, remove them from support structures and increase

their susceptibility to violence and other forms of abuse. When analyzing the

occurrence of these acts of violence in the context of intersectionality, the

events in question can not be regarded as random instances of aggressive

behavior, but are organically connected to the social, political, and cultural

setting of the region. The sexual violence against the women of Kashmir is well

captured by the alleged mass rapes and torture that occurred at Kunan and

Poshpora in February 1991 by the Indian army. The fact that these atrocities

were not officially recorded for years make it apparent that rape is a

continuation of war where factors such as gender, ethnicity, and conflict

politics deepen the gap between accountability and justice.

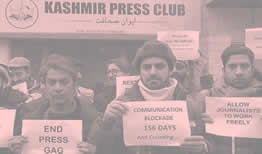

The counter-offensive tactics employed by Indian state in Kashmir is marked by a distinctly gendered tone that is communicated through the language of domination. Two reports are published by UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in the year 2018 and 2019 that give a detailed account of India’s gross and systematic violation of human rights in IIOJK. These reports accuse India of employing pellet gunshots, extrajudicial killings in the disguise of cordon and search operations, arbitrary arrests and detentions, and torture against the civilian population, journalists, political and human rights activists in Kashmir. Regarding this, they specifically point out to the AFSPA and PSA shielding the Indian occupation forces committing cruelties against the people of Kashmir. According to a report by Kashmir Media Service, updated on March 8, 2023, women of Kashmir are being described as the worst-suffering victims of Indian state terrorism in IIOJK.

Indian forces sexually harass, abuse, and use

violence against Kashmiri women. The report shared an experience where Police

and Indian Army personnel raped a woman and her daughter during a cordon and

search operation in the Tral area of Pulwama. The report also stated that

Indian forces are using rape as a weapon of war with an aim of subduing the

Kashmiris through defeatism. This sexual subordination of women stands as not

only an egregious violation of public power but also as a means of asserting

and perpetuating power and dominance over individuals, families, communities,

and, indeed, the entire Kashmiri society. In this way, Kashmiri women are raped

not because of the gender but also because they are Kashmiris, and part of the

‘other’ ethnic group. Here ethnicity and gender, two distinct categories, have

become more defined by each other due to the ethno-nationalist approach adopted

after August 5, 2019, when the autonomy of Kashmir was repealed.

Psychological

and Mental Health Effects

The

impact of the laws such as AFSPA and PSA are immense in terms of the

psychological and mental health of the individuals who are subjected to suffer

under those laws. Kashmiri women constantly remain in a state of chronic trauma

as a result of which, they suffer from high incidences of PTSD, depression,

anxiety and stress. These mental health issues are worsened by the continuing

militarization of the region, which breeds cult of fear among the entire

populace. For example, women who were left to be head of households because of

detainment or abduction of their husbands/fathers/sons will experience stress

and anxiety as they have to take up other roles and pay bills. Many of them

find themselves with no access to any form of mental health care or even support

systems, which only worsens their psychological state.

The

records from Srinagar’s Hospital for Psychiatric Diseases reveal alarming

trends. The outpatient department, which was extending its service to about 100

patients per week in the early 80’s is now handling more than two hundred and

three hundred patients on a daily basis. These patients include women

especially those within the age of 16-25 years. Mental health issues are still

a taboo in this region, hence, the statistics do not depict the true state of

affairs, as a far greater percentage of women would never make it to the

hospital in the first place. This was manifested in Srinagar’s hospitals, where

the overall suicide rate of the late 1990s and early 2000s confirmed that women

were more likely to attempt suicide and record a greater mortality rate than

men.

The

restrictive laws like AFSPA and PSA gives women a sense of fear and unstable

mental state that alters their lives drastically. One student from the

Srinagar’s Government College for Women explained that due to constant

unpredictability of the life under militarization, people turned to religion.

Indeed, such a shift is representative of the contemporary trend, wherein,

religion stands as the shelter for one with a constant experience of trauma and

repression. Even though such behaviors give a momentary escape, they reveal

just how much the mind suffers living in a context where one’s safety and

health is constantly threatened by the government. These cases of aggression of

laws toward women in relation to psychological trauma give evidence of how

legal and systematic oppression work in women. Moreover, the unavailability of

mental health services in IOJK as a result of the conflict, and the state’s

inability to cater to women’s rights is a sign of their continued

marginalization in the region. Tackling this crisis does not simply entail a

readiness to cope with the mental suffering of women but also analyses how such

legal oppressive laws make them suffer in the first place.

A

Socio-Economic Crisis

A

feature that is generally not highlighted in the case of Kashmir is how the

lower middle-class people especially the women and girls have been worst

affected. The conflict that has been manifested by the militarization of the

region has caused drastic loss, with estimates showing that about 60, 000 men

have been killed. When husbands, sons and other male relatives are permanently

absent, the levels of family incomes have been considerably lowered and many

families are now headed by women. This economic pressure is more felt by women

in such households, since they are now faced with the new roles of being

economic providers in a society that was earlier characterized by male

providers. This is exemplified by an increase in work force of female children

by 45% in the rural areas and 67% in the urban areas of IIOJK.

Similarly,

influenced by the conflict, the female education in Kashmir has also been worst

affected. Systematic and deliberate targeting of schools and other institutions

of learning by military forces enhances the threats of fear and insecurity,

especially to school going girls. This has made school drop out rates of girls

to rise significantly due to the ever looming danger of being sexually harassed

or abused by military personnel. Stories of physical contact search,

embarrassment and molestation by security forces especially in the rural areas

have compounded this problem. Failure to report these incidents is attributed

to the fear of social rejection hence making the young girls as well as their

families more insecure.

Case

Study of Parveena Ahanger

Despite of these enormous odds, women of Kashmir are not silent sufferers only. Many have left their homes to become the vanguards of change in the fight for justice and combating violence. For instance, Parveena Ahanger, an aging mother who after losing her son took up leadership in the Association of Parents of the Disappeared Persons (APDP) is enough to illustrate the strength of women in Kashmir. These women, who have changed the meaning of being a victim, are now bargaining in various levels, seeking justice and equality, fighting against long- standing violent atrocities that are claiming the lives of thousands of persons.

Taking in account of her multifaceted struggle since the disappearance

of her son Javaid Ahmad, she said : “When I went out of the home, to search for

him I was a different person. Every morning when the sun comes up, I felt like

there is a long fight ahead. Eventually, I turned to “sanglaat/iron”; there was

no stopping me. Not even my husband. He would for many years scold me, he would

threaten to divorce me every single day. He would tell me “forget that boy, we have other children, stop wasting time in the

protests, stop bringing shame to the family by sitting in public”. He would

tell me that I am destroying the entire family. He was also right too, whenever

my other children required my attention, I was not available. My husband would

remark that this is not what an ‘asal zanan/good woman’ would do? My relatives

would turn their faces the other way, when they saw me in the park or on the

streets. They would say, Parveena is a gone case, she is acting like a loose

woman now.

I am a mother; a mother is a mother, she cannot let go her child like that. What can one hold onto when a son has been kidnapped from the bosom of his mother? If I can not be a good mother, how can I be a good woman? I feel like in front of the mirror I am looking at an unhappy woman, who is waiting for her son. The old me, looks so blurry under all this suffering, she is barely there. At one point, I was happy and joyous making others to laugh. I used to be “zindeh-dil,” I used to be brave, but now I am not the woman that I used to be. It made me feel like I am not just any woman out there after the incident. What more could I do as my pain was too intense. I am still afraid he is outside the door or the window, I get attacks as I continue staring at the door even when it is the wind that knocks, I always think it might be him knocking.

I even

exposed my face, I stayed in the streets, I chased after army officers and

politicians, anyone, anyone who can assist in locating my son. The men looked

at me thinking I was crazy; they called me “pagal maouj/mad mother”. How can I

be sane, even God will forgive me, I am a mother, I gave him birth – my heart

has been taken out of my body, my womb has been injured, scarred; I do not care

if my hair is showing. I would have gladly remained locked inside the four

walls of my home but the pain of losing a child brought me out here. One day,

these soldiers will understand the feeling of disappearing people. They too

will suffer and so will India.”

To

deconstruct Parveena's narrative and reflect on how her identity as the mother

of a disappeared individual has surpassed all other identities, we can analyze

her experience through the lens of Intersectionality. Intersectionality guides

us in comprehending that these identities are not separate but intertwined and

create different experiences of oppression and survival. Parveena, being a

mother of a disappeared son also claims her identity as a Kashmiri woman living

in a conflict prone society in which women and mothers in particular are

navigating a perilous territory. As a woman, she is expected to remain passive

but at the same time, as a mother, she has to stand up for her son; this forms

the core paradox in her identity, which is both susceptible to resistance and

suffering. The judgment she undergoes, as a woman is not only restricted in

terms of gender but in the political climate of Kashmir that focuses on the

opposition she gives to the existing power dynamics.

Reflection on Her Identity

Analyzing Parveena’s story, one can understand how the identity of the mother

totally overcomes every other identity. The disappearance of her son wiped out

the person that she used to be (a zindeh-dil woman) and turned her into an

emblem of protest. That maternal role she assumed altered her very being,

pushed here to go against traditions and endure public embarrassment, not to

mention mourning. Her miseries are not solely personal but are reminiscent of

the socio-political circumstances of Kashmir where every women in general and

mothers in particular fight this protracted battle. Continued societal shame

and her husband’s dismissal underscore the effects of both individual suffering

and collective injustice. Her turning into “sanglaat” (iron) is a direct,

forceful commentary on the ability of the role of a mother, specifically in

such despairing conditions, which not only redefines her being, but also erases

all other aspects of her nature, thus making her determined and vulnerable,

heroic and victimized, all at once.

Her

determination not only symbolizes the strength of the Kashmiri women, but at

the same time, it also unmasks the prejudice they have to endure because of

their multiple marginalization. Parveena’s story shows that the on-going

conflict in Kashmir has severe damaging effects on the psychological well-being

of women, especially mothers. Her case study is not solely about a mother

mourning for her lost son; it is also about how a woman subverts conventional

gender roles while advocating for her rights under oppressive laws such as

AFSPA and PSA. In her journey, Parveena uses three idioms; “sanglaat” (iron),

“buth” (face), and “metch” (crazy) to express how she transform. These are culturally

rooted Kashmiri phrases, that reflect power, resistance, and transition from

conventional gender expectations. The terms ‘sanglaat’ used by Parveena

represents her new found power and purpose; ‘buth’ refers to the aggressive

public character that she acquires in order to demand justice for her son. The

term “metch” refers to madness and mysticism, as the degree of her grief and

determination is brought into spotlight. From Parveena’s case study, it is

clear to see the emotional, psychological and social effects of conflict on

women particularly when they lose their beloved ones and how their identities

are redefined by conflict.

Legal and Advocacy Measures for

Combating AFSPA and PSA

Since Kashmiri women suffer multiple oppressions under AFSPA and PSA, there is

a need for legal and advocacy frameworks to support the rights of women in the

region. All of these strategies must be located within national and

international human rights frameworks and must be given utmost primacy in

relation to lived experiences of women of Indian occupied Jammu and Kashmir.

Mainstreaming of UNSCR 1325

into Domestic Litigation

Despite AFSPA and PSA being repressive legal instruments utilized by the Indian

state, there are proven and viable legal approaches towards combating the

implementation of these laws: The most crucial of which is integrating the

UNSCR-1325 resolution into domestic litigation. UNSCR 1325 provides for the

protection of women and girls in conflicts as well as underscore the need for

women’s participation in the peace processes. Therefore, lawyers and human

rights organizations can file petitions in Indian courts on the grounds that

AFSPA and PSA are unconstitutional since they infringe Indian obligations under

the UNSCR 1325. This strategy does not only raise the gender impacts of such

laws but also synchronizes the legal advocacy with the International human

rights norms. This stresses that the gender-sensitive change must be made with

utmost consideration of the situation of the women in Kashmir and it has

simultaneously highlighted the importance of participation of women in the

legal and political process.

Public Interest Litigation (PIL) and Gender-Sensitive Reforms

Another way through which the implementation of

AFSPA and PSA could be resisted is through Public Interest Litigation (PIL).

Activists can then use PILs to call for gender-sensitive reforms that will

bring these laws in-line with UN SCR 1325 and other International human rights

instruments. These reforms’ objectives would be to mitigate the adverse impact

of such laws on women and guarantee their legal rights. Consequently, PILs can

also be used to challenge the impunity and arbitrary killing of the victims of

violence under AFSPA and PSA. When the gender dimension of these violations is

revealed, activists can work to reform laws and gain increased legal protection

for women in conflict areas. Such strategy would entail engaging legal

personnel, human rights bodies and women activists in order to make legal

arguments related to this matter and anchored to domestic and international

laws.

Leveraging International Legal

Frameworks

Besides domestic litigation, there is a need to tap into international legal

instruments in order to compellingly oppose the actualization of AFSPA and PSA.

About this, one can file cases in International Court of Justice or any other

International tribunal with an argument that these laws contradict to

international norms and regulations including UNSCR 1325. This approach while

difficult and likely to encounter legal and political barriers, goes a long way

to raising awareness of these laws across the globe and increases pressure on

the Indian government to change the law.

The

second approach is to rely on CEDAW commitments that was signed by the Indian

government The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination

Against Women (CEDAW). Since India is a party to the Convention on the

Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the Indian

government can be encouraged to make AFSPA and PSA compliant with CEDAW and UN

Security Council Resolution 1325. If such issues are taken to the CEDAW

Committee then they can lead to international pressures to change the laws at

the domestic level.

Conclusion

This research under intersectional lens provided a clear understanding of how the restrictive laws like AFSPA and PSA affects the lives, security and well-being of women in Kashmir in Indian Occupied Jammu and Kashmir. By focusing on their multiple intersecting identities, this study demonstrates how physical, sexual, psychological and socio-economic factors amplify the risks faced by women in Kashmir. Case study of individual like Parveena Ahanger, a well-known human rights activist and an advocate for the missing people, revealed how gender and state oppression combine to impact current and future experiences of women and subject them to increased vulnerabilities under oppressive state structures. In documenting and analyzing these particular encounters, the study adds to the ongoing debate on gender, conflict and state violence.

It calls for better

implementation of gender responsive measures and strategies for implementing

policies that consider the multifaceted impacts of conflict on women. The

findings therefore – call for legal reforms and advocacy within Kashmir and

International forums that places the issues of women in the forefront. It is

therefore mandatory, that while arguing against AFSPA and PSA, one must

question India’s commitments under the WPS and CEDAW framework, to which the

country is signatory. Women Peace and Security agenda is a set of agendas in

the UN Security Council with the primary goal of defending women in armed

conflicts and engaging them in the peace process based on UN Security Council

Resolution 1325 and others. In this manner, litigation efforts can also

demonstrate that AFSPA and PSA are not only unconstitutional, but also violate

India’s International obligations.

Bibliography

- Agarwal, Aanya. "IN

THE INTERSECTION: WOMEN’S EXPERIENCES IN KASHMIR." Int. j. of Social

Science and Economic Research 7, no. 7 (July 2022), 1838-1845. Accessed

July, 2022. https://doi.org/10.46609/IJSSER.2022.v07i07.007.

- Bhat, Adil. “Kashmir: History, Politics, Representation.” Contemporary

South Asia 26, no. 3 (July 3, 2018): 367–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2018.1507739.

- Bhattacharyya, Rituparna. “Living with Armed Forces Special Powers

Act (AFSPA) as Everyday Life.” GeoJournal 83, no. 1 (September 22,

2016): 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-016-9752-9.

- Bouzas, Antía Mato. “Resisting Disappearance. Military Occupation

& Women’s Activism in Kashmir, by Ather Zia.” European Bulletin of

Himalayan Research, no. 56 (September 10, 2021). https://doi.org/10.4000/ebhr.82.

- Chandak, Sujit R. “Do You Remember Kunan Poshpora.” Contemporary

South Asia 26, no. 1 (January 2, 2018): 99–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2018.1433399.

- Connah, Leoni. “International Law vs. Domestic Law in Kashmir.” Peace

Review 33, no. 4 (October 2, 2021): 488–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2021.2043008.

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality,

Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law

Review 43, no. 6 (July 1991): 1241–99. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1229039.

- Fatima, Hareem , Syeda Shafia Batool, and Nabeel Hussain. “Gender

Dynamics in Indian Illegally Occupied Jammu and Kashmir: Exploring UNSCR

1325 through an Intersectional Lens.” Cissajk.org.pk Vol I, no. 1

(2023). https://strategicperspectives.cissajk.org.pk/gender-dynamics-in-indian-illegally-occupied-jammu-and-kashmir-exploring-unscr-1325-through-an-intersectional-lens-pdf/.

- Kazi, Seema. “Between Democracy and Nation: Gender and

Militarisation in Kashmir.” ResearchGate. unknown, 2008. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297280043_Between_democracy_and_nation_Gender_and_militarisation_in_Kashmir.

- Kazi,Seema “Women, Gender Politics, and Resistance in Kashmir.” Socio-Legal

Review 18, no. 1 (January 1, 2022): 95–117. https://doi.org/10.55496/aukx4646.

- Persons, Disappeared. “Association of Parents of Disappeared

Persons (APDP Kashmir) - Official Website.” Association of Parents of

Disappeared Persons, August 8, 2018. https://apdpkashmir.com/.

- Rashid, Mantasha. “Violence against Women in Kashmir: Personal and

Political : WestminsterResearch.” Westminster.ac.uk, 2022. https://westminsterresearch.westminster.ac.uk/download/d3621272532e2c1c41a1e1817a598f3aad5e34c39d229fcd5edb92c35e6796b8/2725441/Rashid%20Final%20Thesis.pdf.

- Tehelka WebDesk. “A Cup Full of Woes for the Valley’s ‘Half Widows’

| Tehelka.” Tehelka.com, January 16, 2022. https://tehelka.com/a-cup-full-of-woes-for-the-valleys-half-widows/.

- Zia, Ather. “The Politics of Absence: Women Searching for the Disappeared in Kashmir,” January 1, 2014.Zia, Ather “The Spectacle of a Good Half-Widow: Women in Search of Their Disappeared Men in the Kashmir Valley.” PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 39, no. 2 (November 2016): 164–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/plar.12187

Related Research Papers