Humanitarian Crisis at the LOC: Security of Life and Livelihood

Humanitarian Crisis at the LOC: Security of Life and Livelihood

Abstract:

The following paper concerns the

micro and macroeconomic grievances faced by the people living in close

proximity to the Line of Control (LOC), especially those located within a 5–10

kilometre radius of the area it encompasses. This study posits that the volatile

nature of the line, coupled with its crude boundary demarcation and the

incessant military action surrounding it, have all contributed to the financial

woes of non-combatants present in the region. The research surveys relevant

statistics relating to the impacted trade, commerce and infrastructure of these

vulnerable zones, drawing connections between these factors and developments

across the LOC in both Indian and Pakistani-administered territories.

By:Muhammad bin Abbas

Studying Sociology, Business Studies

at Beaconhouse College Programme

It

concludes that the aforementioned issues would indeed be alleviated in the

absence or betterment of the current LOC. However, it does not present

replacing the line with a “proper” internationally agreed-upon border as a

viable policy recommendation, as such a proposition is unrealistic in the foreseeable

future. Instead, it purports domestic projects, facilitation measures and the

conduction of bilateral CBMs between India and Pakistan to be the general

direction the problem needs to be veered toward to effect positive short-term

and long-term change. The significance of this paper lies in its more localized

approach to addressing the matter, as opposed to the usual grandiose

discussions focusing solely on long-term solutions, unnecessary intervention

and absolutes. The primary objective remains assessing the condition of and

providing empowerment to the locals themselves within the broader context of

India-Pakistan relations.

Keywords:

Line of

Control (LOC), India-Pakistan relations, Kashmir conflict, microeconomic

grievances, macroeconomic challenges, border demarcation, bilateral

confidence-building measures (CBMs), trade disruption, infrastructure

development, regional instability, localized empowerment, community-centric

solutions.

Introduction:

Having endured for over 75 years, the Kashmir issue has yet to simmer down, with India and Pakistan continuing to espouse their claims to the vast area encompassing the vale of Kashmir and beyond, retaining irredentism as a core part of both their historical and current policies. The ceasefire line splitting the former state of Jammu and Kashmir was demarcated in 1949 under UN supervision as a “complement of the suspension of hostilities” after the first Indo-Pak war of the preceding year. Since then, the ceasefire line was never altered to a lasting extent and bisected AJK from the Indian-administered state of Jammu and Kashmir, from which Ladakh was designated a territory in its own right as per the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act 2019. A significant development surrounding the ceasefire line was specifically its being renamed to the Line of Control in the Simla Agreement of 1972.

The boundary was an honorary one, however and

excursions have been regularly interspersed throughout the course of its

history. Even since the Indo-Pak ceasefire agreement of 2003, escalations

between the armed forces at the LOC have persisted, mostly taking a toll on the

civilians living there and/or their residencies. In light of this, financial

possibilities in the region have been greatly mitigated and a constricted

business environment has been created. Despite the plight of the affected

people being an oft-quoted consideration in most discourses surrounding the

Kashmir issue, markedly little research has been conducted relating to the

impinged economic capacity around the borderline itself.

Beyond doubt, favourable work conditions are an unalienable right, one that Kashmiris living on the borderline have been unjustly deprived of. Due to the designated LOC not being an internationally agreed-upon border, it is highly violable and has thus been perpetually subject to ceasefire violations and skirmishes. Consequently, military mobilizations, acts of violence and artillery shelling on several points along the borderline have seen a significant increase, leading to a highly regrettable but preventable loss of life and security. The continued occurrence of such instances has instilled an atmosphere of fear amongst the general populace, with their fear for their lives superseding any aspirations they may have had. This constant terror preludes psychological effects on the population, such as trauma and distress.

In particular, the psycho-social and

economic hindrances suffered by the border populations owing to the demarcated

line have been neglected in relevant political discussions. For example,

civilians have had past economic opportunities, such as cross-LOC trade (e.g.,

that of Lipa and Neelam), diminished due to indiscriminate firing and

blockading at the border. Other impacts have been afflicted less violently but

proven to be just as restrictive, i.e., the bifurcation of certain villages

through which the line runs. Worse still, mass displacement and forced vacation

of the agricultural land in the area have left several destitute. As one

Kashmiri said to Al-Jazeera: “We are homeless in our homes.”

With around 300 villages situated on

the Pakistani side of the border alone, thousands of Kashmiris have been

affected already, not to mention the struggles of those in IOJK. With the scope

of the situation in mind, this subject in particular has been chosen for this

research as its ambit has seen a drastic resurgence, the consequences of which

are usually only viewed through the Indian or Pakistani lens. With both nations

endeavouring to increase their respective spheres of influence in the area via

the LOC, the effects on the lifestyles and work opportunities of Kashmiris at

the border are frequently overlooked in academia, as highlighting state

contestation and geopolitics are favoured in lieu of them.

To amend this oversight, this paper

is gravitated towards the peoples’ diminished freedom of commerce/income and

minimal economic prospects owing to border conflict. As such, it is only

pertinent to renew interest in and examination of the role of the LOC in these

struggles. While political dialogue regarding Indo-Pak contestation over

Kashmiri territory is important, it is also vital to acknowledge the issues

plaguing those at the border and their livelihoods (as has been done in this

report) so that they may be alleviated in the foreseeable future. With quality

of life and developmental work being directly affected, a holistic

demonstration of this becomes essential. Thus, the significance of this

research lies in its unique and multi-perspective approach to broach the

questions posed and delineate their causes and courses of action.

As this paper is concerned with

theoretical contribution to the subject matter, the report will predominantly

base its findings off of qualitative research, the grounds of which lay on data

analysis and literature review. Consultation of various news reports, articles,

books (both online and physical) and government reports has served as the basis

of data collection for this research. The statistics obtained from these have

been used to contextualise the matter at hand and provide much-needed insight

to support the analysis. A classification model has been adopted to dissect the

different facets of the matter at hand (social, cultural, etc.) and assort them

as prudent. Resultantly, each element was viewed congruently, in relation to

each other, to formulate a suitable analytic framework that addresses and

potentially resolves them as a whole. This approach has reconciled multiple

viewpoints and ensures a comprehensive yet cogent analysis.

The following research is not devoid

of a few limitations, with its foremost shortcoming being the lack of surveys

to gauge the public consensus in the studied areas. Although this venture had

initially been planned and attempted online, the data pool gathered proved to

be insufficient for the drawing of any concrete conclusions. Additionally, the

participants in this activity seldom consisted of Kashmiris or people of

Kashmiri descent and were instead concentrated in South India and Punjab,

Pakistan. Another limitation was the dwindling amount of reasonable official

figures regarding demographics in IOJK, as many tended to be exaggerated and/or

biased in some form.

Although there is plentiful pre-existing literature tackling the loss of life amidst the tensions at the LOC, the economic facet of the issue is not as frequently mentioned, even less so without associating it with the macroeconomic implications on the nations of India and Pakistan as a whole. However, there is no shortage of works examining the strategic factors affecting the target of this research. Peter R. Lavoy’s book, “Asymmetric Warfare in South Asia,” for example, though primarily concerned with the scope of the Kargil War, details the strategic points and important routes upon which the involved armies’ efforts were directed. Such notes may be used to derive the potential impacts faced by the bystanding border-folk. Other works, namely “Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unfinished War” by Victoria Schofield and The IPA’s project, “Kashmir:

New

Voices, New Approaches,” served as instrumental consultations to impart how

thoroughly the subject of this research concerns Kashmiri sentiment, with the

latter even bringing up the economic impacts of the conflict on Kashmiris,

albeit briefly. These mentions usually pertain to districts further away in

IOJK, with the exception of communities in Poonch. While the selective

literature might initially seem to deviate from the subject matter, it is

important to note that a multifaceted issue such as this is also influenced by

variables outside the domain of this research. Therefore, it has been viewed

through a wider scope, keeping geopolitical contexts in mind while suggesting

potential ways forward.

Impact of Violence at the LOC on

Economic Development in Afflicted Localities

Being a mostly agrarian and pastoral

society, the Kashmiri settlements at the border are highly dependent on land

for cultivation; AJK as a whole has 30–40% of household earnings based on

farming. As such, the economic environment becomes significantly unstable in an

area where access to arable land is necessitated, yet access to said land is

never guaranteed.

Kashmiris have already been

displaced from the fertile meadows of their ancestors in Eastern AJK, with even

the extensively terraced Lipa Valley having lost productive land since 1971. In

Arnia and RS Pura, civilians reported that skirmishes at the LOC may prevent

them from even harvesting the paddy they had already grown; they were

subsequently moved away from their farmland entirely in accordance with India's

border depopulation strategy. The issue would hardly have escalated to such

drastic measures had the border been a formalised one, with reduced CFVs. As

they have had their foremost means of income taken away due to circumstances

beyond their control, the border-dwelling populations cannot be expected to

maintain prosperous households in the face of both terror and rampant

inflation.

Similarly, the rearing of livestock

also poses difficulties due to the conflict at the border. Grazing is severely

reduced due to constant shelling posing threats to the “baikhen” (shacks for

livestock) raised on the slopes, which puts livestock situated within them in

mortal danger. The situation isn’t helped by soil degradation caused by CBWs

used on the more sensitive terraced fields, rendering them unsuitable for

plantation and effectively becoming useless for agricultural practices such as

growing fodder crops. Further still, military action is seldom limited to just

livestock. Owing to the pronounced and sometimes sudden seasonal temperature

changes in the region, shepherds and herders must constantly rotate their stock

and venture to new fields. However, their proximity to the LOC brings them

under the threat of shelling and border crossfire, sparking events of violence

causing bodily harm or even proving fatal.

With all these factors mounted

against local producers, maintaining an output that sufficiently provides for

their families becomes a near impossibility. Even fortunate farmers toil in

fear of the fact that their efforts spanning several months are consistently at

risk of being torn down at any time the border forces re-exert control in the

area through military force. These people are hard-pressed to find other

avenues of generating income, considering how the fertile yet sparsely

populated lands of their abode do not lend as favourably to commerce and

cottage manufacturing as they do to agriculture. When this primary mode of

subsistence is put under pressure, however, any semblance of stability becomes

unattainable and mere survival becomes the new priority. This lack of financial

security and assurance ensures that the Kashmiris caught in the midst of the

conflict zone never rest easy, even in times of declining CFVs; after all, what

use is peace when the war before has left you destitute?

Another significant issue with

regards to the instability at the border is its effect on local architecture.

Regardless of whether you take into account AJK or IOJK, it is imprudent to

deny that villages within 5 kilometres of the LOC on either side have a

vulnerable status. Military mobilisations nearby not only bring the locals

under the line of fire but also their residences and other erected structures,

including livestock holdings, shops, schools, etc. Usually erected in haste,

these venues can hardly be expected to adhere to structural integrity standards

followed elsewhere. Still, it is a distressing notion to assess just how

vulnerable they are, housed in perpetual instability.

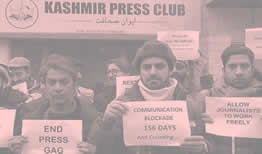

Shelling, in particular, inadvertently targets any sort of construction across the border, thus causing the destruction of houses, water and electric supplies, educational centres, etc. This, compounded with the 35% primary school dropout rate in the region on the Pakistani side, renders educational development highly difficult. The Nagdar high school is a notable example, as it was destroyed by Indian shelling and even killed 38 children studying there. Other forms of infrastructural development and economic hubs have also been brought directly under the line of fire. Nearby markets such as the Kel Bazaar and Jura Bazaar were both set ablaze by similar shelling, directly impacting the income and prices of goods for the locals.

The usage of less conventional and reserved arms, such as flamethrowers,

has been documented in similar cases, highlighting the Indian military’s

disregard for needless property damage in their military exercises. These

excursions go beyond spheres of control and assertions of dominance, as the

weapons employed affect a scale of damage that remains prominent even after a

long term. Conflagration and incendiary practices are particularly devastating

as they damage the infrastructure of an area to such an extent that it becomes

irreparable for the locals, as constructing the site anew would require

external funding. The limited connectivity of these regions alongside constant

CFVs results in such support becoming impossible to administer.

With this constant bombardment

limiting the level of construction possible in the afflicted areas and

levelling pre-existing constructions, business activity as a whole becomes

entirely limited in its domain. Inaugurating marketplaces and amenities

requires normalcy, which the borderline is unfortunately deprived of. Economic

productivity, even on a smaller scale, is only entailed by a robust or at least

stable setup of infrastructure serving as a local hub for commerce, trade, etc.

Without access to this, the Kashmiris on the border will only find it

increasingly difficult to build solid trade networks and establish centres of

business that allow for entrepreneurship to arise. As of now, the regional

economy exists in fragility and therefore continues to attract minimal

governmental and non-governmental investment, creating an unfortunate cycle of

economic adversity. With this in mind, local economic growth remains unlikely

and even economic internalisation is not fully feasible. And so, any

improvement in the quality of life for the border populations is never quite

brought about.

Effects of Kashmir's Delimitation on Economic Prospects for

Locals

Historically, the regions of Jammu and Kashmir have been thoroughly connected for the conduction of trade activity and the passage of East-West traders, as shown by the ever-thriving internal trade of rock salt, fruit, honey and nuts. More recently, India and Pakistan resumed cross-LOC trade in 2008 as a CBM, reinstating the historical routes connecting Muzaffarabad and Srinagar as well as Rawalakot and Poonch. By July 2011, barter allowance was extended, with a greater volume of goods being exchanged across the border at a remarkable four times a week. Carpets, shawls and the like were also included in the exchange, reinvigorating the formerly underdeveloped cottage and textile industries in the relevant areas. However, in 2019, upon India’s abrogation of Article 370, Pakistan’s hand was forced to end the trade agreement in protest.

In response, India implemented its own suspension of

trade along the border, especially that of Uri and Chakan Da Bagh.

Consequently, the relatively jovial atmosphere of cooperation which had

culminated around both sides of the LOC was replaced with despondency and

financial strife. As the Trade Facilitation Centres along the border ceased

operation, the tradesmen who had managed their dealings up to that point were

inconvenienced almost immediately. The cessation of the aforementioned

Uri-Chakothi and Tetrinote-Chakan Da Bagh trade alone directly impacted around

1,200 traders on both sides of the border.

Overall, the economic implications

for both populations were even more dire, with the loss of estimated freight

revenue streams for regional transporters amounting to 66.4 crores (INR). This

sudden loss of labour and economic disruption highlights how the delimitation

at the LOC is entirely a hindrance, one which limits the extent to which

Kashmiris can cooperate with like-minded businesses across the border and have

their economy flourish through mutually beneficial trade. The Indo-Pak corridor

has historically proven to be too fruitful to ignore completely; hence the

trade volume flowing through it has continued at considerable amounts, despite

the political tensions between the neighbouring nations. Logic dictates that

opening up the vale of Kashmir on the trading front will offer similarly

prosperous results. As Victoria Schofield puts it: “Even in the darkest days of

the Cold War, when West and East Berlin were divided, there was a Checkpoint

Charlie through which people crossed from one side to the other. Why then not a

Checkpoint Chakothi? It would be a small step which might mean a new

beginning.”

Delimitation has also impeded

mutually beneficial Indo-Pak border agreements, since the problematic and

heavily contested LOC lacks the permanence and relative stability of the rest

of the internationally agreed-upon boundary of the two countries. As per the

Karachi Agreement of 1949, both nations had come to the consensus that military

construction within half a kilometre of the border, later amended to 150 metres

in the Border Ground Rules Agreement, was to be restricted. However, when

taking into account their held territories in Kashmir, neither stipulation has

been adhered to or considered as seriously as they should have been, with

either defensive construction at the border seeing a continuance or established

camps refusing to relocate.

When viewing this from a civilian

perspective, constructions at the border, such as the border outpost at Pittal,

only impede future development of local villages, with defence spending once

more gaining precedence in the area over civilian infrastructure. As such, the

issue will only persist as each side is goaded to respond to the other’s

initiative and renew out-posting. Subsequently, not only does regular

construction become impossible, but any pre-existing buildings also continue to

be pressurised, falling under more and more spheres of artillery lines, hardly

ideal candidates to expand into market centres.

Tourism is another activity that

presents an incomparable opportunity for the border people to foster economic

connectivity and an influx of wealth through both domestic and international

tourism. However, this expedient is rendered invalid due to the instability and

conflict at the LOC; for how could the secure passage and return of tourists be

guaranteed when even the locals live in constant fear of threats to their

lives? Although the rest of AJK has seen significant faith placed in its

potential for tourism through the utilisation of its scenic beauty, localities

around the LOC itself remain bereft of this faith and thus the chance to

develop tourist sites remains void. This is largely due to the impractical

delimitation of the borderline itself, which enables violent cross-LOC

exchanges and skirmishes that negate any sort of tourism-related prospects at

all. While the introduction and facilitation of tourism across the entire LOC

is an understandably unrealistic ideal, there should be no qualms with the

development of tourism in less militarised zones adjacent to the Line, such as

areas on the Eastern front of Upper Neelam.

Civilian interest in nearby regions is indubitable and would be seeing a significant surge akin to the flare of attention received by other parts of Northern Pakistan if not for the tumultuous situation at the border. Foreign attraction would also have been possible when recalling the fame of Kashmir’s valleys, magnificent sites such as that of the Pir Panjal and intricate histories of various other locations. While such tourism is not non-existent, the vast majority favour visiting areas much further from the LOC, such as Srinagar in India and Muzaffarabad in Pakistan.

This has undone what would otherwise have been a great source of

income for people living closer to the Line. If a tourist industry were to

spark up here, a multitude of jobs would be created for the locals as they

could explore this opportunity without any trepidation. External investment

could be seen as the area would further develop, culminating in a much-needed

influx of capital and developmental projects. Additionally, this would enable

the transitioning of local workers from the informal sector to the formal, thus

ensuring a greater degree of financial security and rights. Resultantly,

tourism could well be the key to bolstering economic growth and connectivity

across the LOC.

Conclusion:

Summarily, the research indicates

that the regional conflict has sincerely adverse implications for the

livelihood of local communities caught amidst it. The microeconomic struggles

in the face of this only coalesce into even direr macroeconomic ones throughout

the border territories.

The ever-present threat to the

security of life and work when discussing the Kashmiris living around the LOC

cannot be overstated. Although the Kashmir issue poses and has posed broader

ramifications for the entirety of India and Pakistan, its first and foremost

consequences are imparted upon the people caught in its fray, the Kashmiris

themselves. While those amongst them based in a city like Muzaffarabad, for example,

may be spared from the immediate and direct impacts of contestation at the

border, families in close proximity to it are forced to suffer literal and

figurative wounds from powers they never crossed. Traditional methods of income

have all but become unattainable as military occupation overruns their

homeland, distilling discomfort and anxiety as it does. Even newer modes of

income, such as adapting to tourism, become invalid as well.

On that account, it becomes essential to tackle the situation on a societal and governmental level. While the swift reinstatement of cross-LOC trade is an unrealistic ideal, especially when considering the less-than-negotiable stance of the BJP, a few CBMs are still a diplomatic possibility. For example, the old trade routes could be redirected to pass further south, allowing them to open up at a more agreeable location for both countries. In contrast to the pre-2019 situation, it is possible to reopen only one or two of the prior trading hubs, concentrating all exchanges at just these points to minimise the required surveillance along the border.

To avoid security dilemmas, the states could agree to limit this trade

to official wares for the time being. Admittedly, this would inconvenience

district retailers, but through thorough examination and trade centre

registration processes, their interests may be catered to as well. The

respective intelligence of both parties could share reports from over the

border to ensure there are no discrepancies in the process, building further confidence

and security so that the trade may remain sustainable. Due to the sensitive

relationship between the neighbouring countries, any immediate changes besides

these would be unwise. Rather, this system could gradually be transitioned back

to the old barter system, perhaps in the successive decade or so once the

initial trepidation at across-the-border cooperation is overcome.

Initiatives in AJK, on the other

hand, can be carried out with far greater confidence. To safeguard its border

citizens, the Pakistani government must increment its placements of artillery

protection walls along the roads, possibly extending the coverage onwards from

Jagran till before the outskirts of Taobat. In less connected areas along the

borderline, however, the government must increase the distribution of bunkers

allotted to the boundaries of each district to ensure the safety of Kashmiris

in case of indiscriminate firing and the like.

References:

1.

AJK

Bureau of Statistics. AZAD JAMMU &

KASHMIR, AT A GLANCE 2015. Muzaffarabad: AJK Bureau of Statistics, 2017.

2.

Aman,

Zutshi. “Farmers in R.S. Pura Staging

Protest Sit-in after Being ‘forcibly Evicted from Their Lands’: Kashmir

Times, May 8, 2024. https://kashmirtimes.com/farmers-protesting-in-jammu-against-eviction/

3.

Sherazi, Iftikhar, et al., “Two

Martyred, One Injured after Indian Forces Open Fire at Shepherds at LOC: ISPR.”

DAWN.COM, July 26, 2023. https://www.dawn.com/news/1761520/two-martyred-one-injured-after-indian-forces-open-fire-at-shepherds-at-loc-ispr.

4.

Zafar,

Saleem, et al. “Education under Border

Shelling: Evidence from Schools near Line of Control in Azad Jammu and

Kashmir,” Global Educational Studies Review VIII no. II (June 30,

2023): 367–76. https://doi.org/10.31703/gesr.2023(viii-ii).33.

5.

Shaheen,

Akhtar. publication, LIVING ON THE

FRONTLINES: PERSPECTIVE FROM THE NEELUM VALLEY , 1st ed., vol. 21, Margalla

Papers (Archive; Islamabad: NDU, 2017). https://margallapapers.ndu.edu.pk/site/issue/view/12/130.

6.

Shaheen,

Akhtar. publication, LIVING ON THE

FRONTLINES: PERSPECTIVE FROM THE NEELUM VALLEY , 1st ed., vol. 21, Margalla

Papers (Archive; Islamabad: NDU, 2017).

https://margallapapers.ndu.edu.pk/site/issue/view/12/130.

7.

Anando,

Bhakto. “How Suspension of Cross-Loc

Trade Shattered Uri’s Economy,” Frontline. January 30, 2024.

https://frontline.thehindu.com/economy/how-suspension-of-cross-loc-trade-shattered-uri-economy-kashmir-leaves-thousands-out-in-the-cold/article67751572.ece.

8.

Surya Valliappan,

Krishna. “Caught in the Crossfire:

Tension and Trade along the Line of Control,” Carnegie Endowment for

International Peace, accessed Septemberr 2, 2024.

https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2022/06/caught-in-the-crossfire-tension-and-trade-along-the-line-of-control?lang=en.

9.

Schofield, Victoria. Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the

Unfinished War. London: I.B Taurus, 2000.

10. Happymon, Jacob. United States

Institute of Peace report. Ceasefire

violations in Jammu and Kashmir: A line on fire. 978-1-60127-672–8 (2017). https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/PW131-Ceasefire-Violations-in-Jammu-and-Kashmir-A-Line-on-Fire.pdf.

11.

Tariq,

Naqash. “Azad Kashmir to Celebrate 2019

as ‘Tourism Year,’”. DAWN.COM, November 15, 2018.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1445629.

Related Research Papers